It’s not every day that the measurement of economic statistics is at the centre of a public debate in South Africa. But when soon-to-retire CEO of Capitec Gerrie Fourie suggested in off-the-cuff remarks that South Africa’s true unemployment might be closer to 10% than the official 32.9% figure published by Stats SA, he set off a storm of controversy, drawing economists, policymakers, business leaders and journalists to weigh in on what, and who, should really count as “employed” in South Africa.

Let’s begin with what Fourie (no relation) said:

“What is interesting is when you look at the unemployment rate, we talk about 32%. But Stats SA doesn’t count self-employed people. I really think that is an area we must correct. The unemployment rate is probably actually 10%. Just go look at the number of people in the township informal market, who are selling all sorts of stuff, who have a turnover of R1,000 a day.

“To grow South Africa, we need to understand what is happening there [in the informal market]. If we really had a 32% unemployment rate, we would have had unrest. If you go to the townships, most people have back rooms to rent out, everyone is doing something. If we are talking job creation, let’s go out and encourage these entrepreneurs.”

Labour economists fired the opening salvo. In a letter to Business Day, University of Cape Town economics professor Andrew Kerr acknowledged that there are legitimate concerns about the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) – such as poor quality data on earnings and the puzzling fact that employment numbers are often higher in the General Household Survey than in the QLFS – but insisted, correctly, that the claim Stats SA does not count the self-employed as employed is simply not one of those concerns. Sadly, his otherwise reasoned letter closed with a patronising put-down: “The Capitec CEO should stay in his lane and confine his pronouncements to topics such as borrowing and lending.”

Others jumped on the bandwagon. Author Jonny Steinberg said Fourie had exposed his “intellectual laziness, born from overconfidence”. Former statistician-general Pali Lehohla called Fourie a “random businessman who profits from black communities” who makes “comments on a system he clearly doesn’t understand”. Economics columnist Duma Gqubule concluded that Fourie should withdraw his statement because it “minimises the pain of 12.7-million unemployed people in South Africa”.

So much for encouraging public discourse.

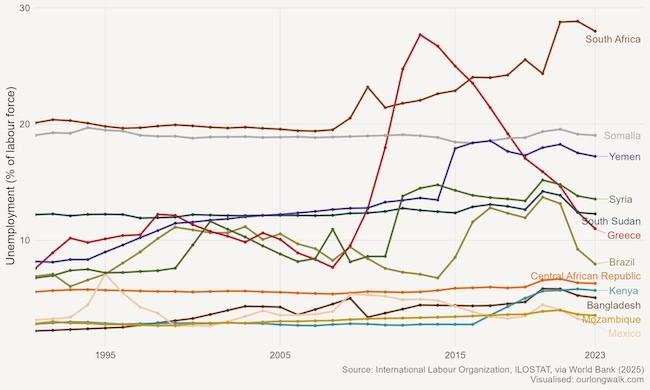

Yet consider the graph below. These are the unemployment rates for a set of countries in the world. South Africa, as you’ll notice, is a massive outlier; our unemployment rate, according to the International Labour Organisation, was 28% in 2023, more than double that of Somalia and Yemen. Greece overtook us for a few years when its GDP shrank by a quarter after the global financial crisis, but it recovered to its usual 11%. Brazil at 8%, Kenya at 5.7% and Mexico at 2.8% all have rates that are barely a fraction of ours, making South Africa’s position not just unusual, but almost incomprehensible by global standards.

At the risk of a lane violation, I have to ask: is this really plausible?

Telling the whole story

It’s not just the Fouries who puzzle over this.

After Fourie spoke, voices from all sides have questioned whether the numbers tell the whole story. The list is far from complete, but it includes trade, industry and competition minister Parks Tau; labour minister Nomakhosazana Meth (whose recent News24 column, I suspect, owes much to ChatGPT); economist Peter Attard Montalto; seasoned financial journalist Tim Cohen; seasoned political journalist Stephen Grootes; and economic commentator Siyabonga Hadebe.

Most recently, News24 editor Helena Wasserman weighed in, offering a sustained critique of South Africa’s unemployment data. She begins with the simple fact that fewer than 29,000 households are surveyed, a number that has remained largely unchanged for two decades, despite a massive rise in population and a country that has undergone dramatic demographic and economic shifts.

Wasserman points out that this reliance on an old and unrepresentative master sample, still pegged to the 2011 census, means that neither rapid urbanisation nor the explosion of new ways of earning a living – think of Uber drivers or Checkers Sixty60 deliverers – are properly captured in our headline statistics.

There are further distortions, she says: respondents have strong incentives not to disclose income for fear of jeopardising grants or facing the South African Revenue Service, while the survey’s design struggles to account for the millions who survive outside conventional employment, from informal landlords to subsistence farmers.

Wasserman argues that the result is not simply statistical fuzziness, but a systematic misreading of how South Africans actually get by, compounded by Stats SA’s well-publicised capacity and credibility issues.

First, Wasserman has done well not to mention GG Alcock. Alcock has become well known for his vivid depictions of township economies and the world of the kasipreneur. He argues that the size and dynamism of the informal sector are vastly underestimated, often citing eye-catching figures for the turnover of spaza shops, township rentals, informal taxis and shebeens to suggest that South Africa’s unemployment crisis is, in fact, a statistical mirage.

But while Alcock’s colourful estimates make for compelling copy, they are not reliable statistics. As academic critiques of earlier private sector research have shown, when numbers are based on rough guesses, selective anecdotes, or methods that cannot be externally verified, they are at best speculative and at worst misleading. Much like the Adcorp figures that once claimed South Africa’s unemployment rate was as low as 5%, Alcock’s big numbers do not stand up to careful scrutiny. No serious labour economist working in this field would accept them at face value.

Second, though I have much sympathy for Wasserman’s concerns about Stats SA’s capacity, she overlooks the weight of evidence provided by Kerr and others who have examined the quality of South Africa’s labour statistics in detail.

Kerr’s research shows that, despite resource constraints and well-publicised challenges within the agency, Stats SA’s core measurement of unemployment remains robust.1 Carefully stratified and weighted samples, along with regular recalibration to account for demographic shifts, ensure that the headline figures, while not perfect, are consistent with best international practice and are broadly reliable.

Third, I think all these critiques miss a larger issue: it is not so much how we measure unemployment, but how we define it. Clearly, South Africa’s outlier status above means that the global definition is incongruent with our context. This is what I think Fourie referred to. But to understand context, we need to understand our history.

Looking to the past

South Africa has not always been a labour-abundant country. In fact, until quite recently, South Africa, as almost every other African country, was labour scarce, meaning that there were too few people for the number of jobs at the prevailing wage rate. Just consider the solution Joburg’s mining bosses came up with at the dawn of the 20th century: bring in, first, Chinese workers and then, when that turned out to be a disaster, African labourers from territories outside South Africa.

Finding historical unemployment rates is particularly difficult – again, because of definitional issues – but where the unemployed were enumerated, I find an unemployment rate, calculated as the number of unemployed over the total population of working age, of about 1% in 1960.

Then, as I explain in Chapter 29 of Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom, South African industries began to mechanise:

“[I]nstead of moving their location [to the homelands], factories mechanised by using (expensive) capital equipment to substitute for labour. It was not only manufacturing that mechanised. Even agriculture – the sector that traditionally employed unskilled labour – began to transform. While the amount of farmland in cultivation declined between 1946 and 1976, the number of harvester combines, a machine used for harvesting crops and a substitute for labour, increased more than tenfold from 1,722 to 23,767. This mechanisation across the economy had an important consequence, one that still haunts South Africa today: by reducing the need for unskilled labour, it gave rise to high levels of unemployment. When black labour unions were unbanned and understandably began to push for higher wages, mechanisation and unemployment were further bolstered.”

Using the same definition of unemployment as above, I find an unemployment rate of 3.4% in 1980.2 The stagnant economy of the 1980s, together with a growing population and the further mechanisation of mining and manufacturing, led to significant increases in unemployment. By 1991, unemployment, using the same definition, had risen to 14.5%.

As South Africa entered democracy, rising unemployment quickly emerged as a defining challenge. The early 1990s brought fierce debate over how to tackle poverty and joblessness in an economy opening to the world. Accession to the World Trade Organisation in 1995 abruptly exposed South African firms, long protected by sanctions, to international competition.

Despite ambitious efforts like the Reconstruction and Development Programme, and the Growth, Employment and Redistribution programme, job creation lagged behind a swelling labour force as more young people, urban migrants and school-leavers entered the market. Labour-intensive industries, in particular, struggled to survive under pressure from rising wages and global competition.

Further unintended consequences soon followed. As my colleagues Rulof Burger, Servaas van der Berg and Dieter von Fintel have shown, education policies in the late 1990s pushed hundreds of thousands of over-aged learners out of school and into a labour market already under strain.3 This sudden shift drove up labour-force participation and revealed a backlog of hidden unemployment, especially among the youth. By 2003, the unemployment rate had surpassed 26%, firmly establishing itself as one of South Africa’s most persistent and visible economic challenges.

Higher economic growth did make a difference, at least if you believe my definition. By 2008, I calculate an unemployment rate of 18%, much lower than before but still high by international standards. But the sad reality is that, because of an era of populist policies and state capture, it would never go down again. Today, we are stuck with an extraordinarily high rate.

The move to informality

What did all these people do who became technically unemployed because of poor education, mechanisation and globalisation? They moved largely into informal economic activities: selling goods in spaza shops, renting out backyard rooms, or providing small-scale services such as hairdressing and street vending. These activities might not qualify as formal employment under the standard definition, but they generate meaningful incomes.

It is precisely these transactions and earnings that Fourie and his team at Capitec detect in their client data, even though these individuals often remain officially classified as unemployed. With 24-million individual clients, 8.8-million of whom are fully banked, and 13-million active app users, Capitec sits on a treasure trove of insight into the workings of South Africa’s informal economy. This is an extraordinarily rich resource for understanding economic activity that remains largely invisible to traditional measurement.

But there is a crucial disconnect: Capitec’s data reveals cash flows, not their source. Some of this money may be genuine informal earnings, but much of it may be grants, remittances or private transfers – income that does not meet standard definitions of employment. And while it is tempting to treat large banking datasets as inherently superior, they face the same challenges of sample selection and representativity that confront all data. Bigger numbers do not solve these problems.

Academic economists, for their part, are right to emphasise the value of rigorous definitions and nationally representative surveys. Yet even though Stats SA does ask about informal employment, the data is far from perfect. Respondents may misunderstand or evade questions, and those conducting or analysing the surveys often have limited capacity; Stats SA’s chronic understaffing is well known.

In addition, some fear that lowering the unemployment rate would dull our sense of crisis. The bigger risk, however, is failing to understand the real economy. Economists would do well to recognise that South Africa’s economy is changing, and that the methods and tools once suited to measuring a formal, industrial economy may no longer capture the complexity of today’s world.

Companies like Capitec have thrived by seeing opportunity in informal markets on a scale that academic economists have often underestimated. Fourie’s optimism, then, should be seen as a call to look harder for new answers, not as gospel truth. We do ourselves no favours by pretending things are better than they are or by ignoring how much the ground has shifted beneath our feet.

What is needed now is a willingness to reimagine our definitions, sources and methods. If economists are willing to step out of their lane, and companies like Capitec are prepared to share their data, we stand a far better chance of understanding South Africa’s true economic landscape. And, perhaps, finally designing policies that meet its scale and complexity.

Johan Fourie is professor of economics at Stellenbosch University, where he teaches economic history at graduate and undergraduate levels. He is the author of Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom (Tafelberg, 2025) and is a blogger at ourlongwalk.com, where this piece was originally published.

Top image: Capitec’s Gerrie Fourie and statistician-general Risenga Maluleke.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

“What did all these people do who became technically unemployed because of poor education, mechanisation and globalisation? They moved largely into informal economic activities: selling goods in spaza shops, renting out backyard rooms, or providing small-scale services such as hairdressing and street vending. These activities might not qualify as formal employment under the standard definition, but they generate meaningful incomes.”

From what I understand, these activities are covered under Stats SA’s definition of employment – somebody who made an income from these activities would not be counted as unemployed in the 33% figure.

The article claims that the definition is the problem, but doesn’t cover what the definition actually is?

Maybe we should learn from other countries.

For instance, when the USA releases its unemployment data, the figures are preceded by the ADP report, which I think is the payroll data. But the USA also does not count people who are no longer collecting unemployment as unemployed.

Then there was a report from the Mises Institute that said employment data is misleading because of a percentage that is functionally unemployed meaning they earn enough to be considered employed but not enough to survive until the next pay day. That is why I think you can’t really count the informal sector as being employed.

Maybe we are doing it the right way.

Talking from SMME viewpoint, I would not totally agree with Mr. Fourie inclusion of us into “employment bracket”. Access to SMME data (deposits transactions and it’s frequency) is not enough to can make this conclusion. SMME’s are struggling to make STEADY or even monthly income. I use electricity that is paid by my husband to run my business, he does not charge me for that, when I make a deposit of R1000 into my account without subtracting my business operation costs, is that profit? is that employment?

Real time transaction data > Survey data

Johan Fourie’s is an insightful and clear voice. His book Our Long Walk to Economic Freedom should be read by all thinking South Africans. I hope to read him more often in Currency