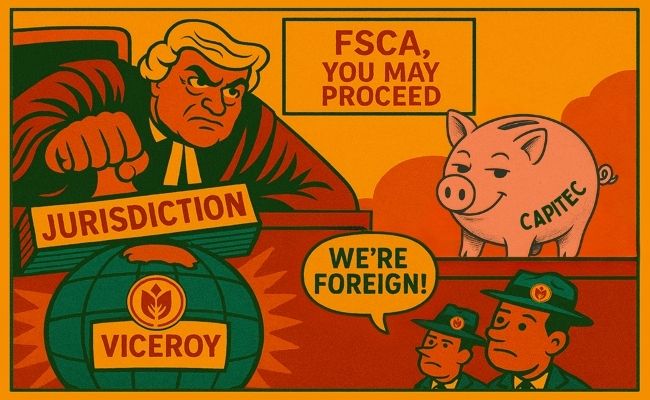

Capitec might take some pleasure from the recent judgment by the Pretoria high court, but several large international banks will be unhappy about it.

The ruling means that the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA) gets another shot at punishing the foreign-based short-seller for trashing the Capitec share price back in 2018.

But it may also mean that the Competition Commission’s chances of prosecuting 13 banks alleged to have colluded in fixing the rand/dollar exchange rate are considerably stronger. And, from the commission’s perspective, the high court ruling could not have come at a better time.

Next month the Constitutional Court is scheduled to hear the latest episode in the forex legal battle that has been wending its way through South Africa’s legal system since 2015.

That is when the Competition Commission is due to argue that local authorities have jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute firms that are not based in South Africa but whose conduct impacts the country. It is remarkably similar to the territory just covered by the Pretoria high court.

That decision relates to Capitec but at its core is an attempt to drag an important aspect of law into the 21st century.

The case being considered by the Pretoria high court was about whether or not the FSCA should be allowed to prosecute a bunch of ill-disciplined short-sellers who managed to knock the Capitec share price for a short while back in January 2018.

The crux of the issue is whether or not the South African authorities – in this instance the FSCA – have jurisdiction beyond our shores. It’s all about the peregrini status of firms that are neither domiciled nor carry on business in South Africa. In terms of centuries-old common law, peregrini entities are not prosecuted because punishment cannot be enforced.

The Capitec sell-off

But let’s go back to January 2018. It was just a month after the hugely dramatic implosion of Steinhoff. A little-known company called Viceroy Research had very promptly put out a remarkably informed report on the murky goings-on at the retail giant.

A few weeks later, perhaps encouraged by the fact it was now almost a household name, Viceroy put out a damning report on Capitec. Titled “Capitec: A Wolf in Sheep’s clothing”, it alleged accounting irregularities, overstated loan book quality and systemic risks.

At the time Capitec was not quite the solid, massively profitable banking entity it has since become and, post-Steinhoff, investors were generally nervy. There was a massive sell-off of Capitec shares, which is precisely what the Viceroy team had been aiming for. (The share price did bounce back reasonably quickly but many investors were hurt by the temporary R10bn slash in market capitalisation.)

The FSCA was not happy. It investigated the matter and in September 2021 imposed a R50m administrative penalty on Viceroy and its three partners for publishing “false, misleading or deceptive statements, promises, or forecasts regarding material facts about Capitec, which they ought reasonably to have known were not true”.

Viceroy challenged the fine, arguing on the basis of the centuries-old peregrini rule that the FSCA lacked jurisdiction given that the reports were produced and distributed from outside South Africa.

In November 2022 the Financial Sector Tribunal agreed with Viceroy and set aside the fine.

So the FSCA went straight off to the high court to have the tribunal’s decision reviewed and set aside. Which is pretty much what the high court has done. It ruled, not unreasonably, that things have changed. “Modern society lives in a global world where the necessity to be present in person has diminished over time. Courts, for example, hear matters virtually and an employee can reside anywhere in the world if the nature of his/her employment does not demand physical presence.”

The court argued that on this issue the common law needs to be developed to ensure effective regulation of financial activity that takes place globally. “The misinformation that was widely distributed and publicised in South Africa by the respondents (Viceroy), had a disastrous effect on one of South Africa’s prominent financial institutions. To absolve the respondents from being liable for their conduct merely because they will at no stage be physically present in South Africa is not in the interest of justice.”

So, in the interest of justice, the tribunal’s decision was set aside and must now be reconsidered.

Constitutional Court to weigh in

The FSCA matter is reasonably straightforward compared to the Competition Commission’s extremely ambitious and complicated case – initially against 23 banks.

One of the commission’s biggest challenges is jurisdiction. Sixteen of the banks are claiming the same “peregrini” status claimed by Viceroy. If successful on this score, they would not even be prosecuted, which would be first prize for large international banks keen to manage their reputations.

The upcoming Constitutional Court hearing relates to a January 2024 decision by the Competition Appeal Court which released 17 of the banks from the commission’s case. The commission promptly appealed that decision – in relation to 13 of the banks – to the Constitutional Court.

At the time, commissioner Doris Tshepe said the appeal will provide the Constitutional Court “with an opportunity to pronounce on whether the South African competition authorities have jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute firms that are based outside of the Republic whose anti-competitive conduct affects the South African economy”.

The Pretoria high court looks to have significantly reduced the banks’ chances of hiding behind the “peregrini” fig leaf. Of course, this far from ensures the commission will ever win this case, but it has brought it a little closer to being able to prosecute it.

The competition commission alleges that, between 2007 and 2013, traders working at banks in Europe, South Africa, Australia and the US conspired to manipulate the rand through information-sharing on electronic and other platforms and various co-ordination strategies. This manipulation – it says – affected the exchange rate, which in turn affected the economy.

(The 13 banks are Bank of America Merrill Lynch International Designated Activity Company, JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, Standard Bank of South Africa Limited, Nomura International PLC, Commerzbank AG, Macquarie Bank Limited, HSBC Bank, USA National Association, Merrill Lynch Pierce Fenner & Smith Inc, Bank of America, National Association, Nedbank Limited, FirstRand Bank Limited, and Standard Americas, Inc.)

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.