This article was originally published on 18 July 2025.

Inside, Joburgers swan about in cocktail attire, air kissing and making small talk. A woman in a slinky, backless gold dress sips champagne, while a gent in a tux whips up the sweeping red-carpeted staircase, headed to the Wedgwood-blue ballroom.

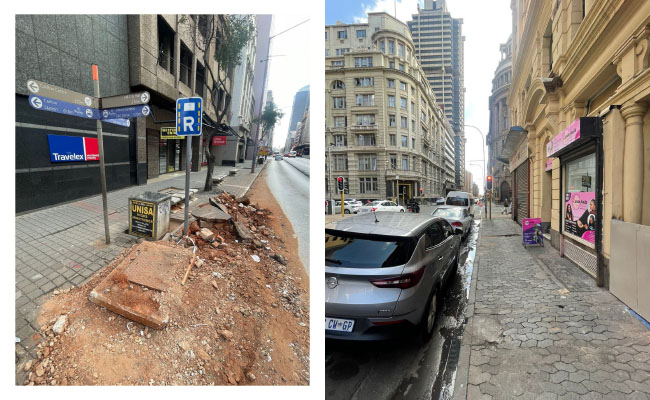

Outside, it’s like a scene from the movie District 9. Shards of shattered pavement and red earth spill into the road and are eclipsed by tatty bricked-up store fronts, haphazard fragments of missing tarmac, and an unidentifiable liquid running down the road.

This is the arresting dissonance today at the Rand Club – Joburg’s oldest private club – which has somehow survived the collapse of the city around it. Until now.

A wildly off-the-mark property valuation from the City of Joburg, combined with a nearly R1m bill for arrears rates, threatens to finally draw the shutters on the Grande Dame of genteel escapism, founded in 1887, the year after the city of gold was founded.

It would be a dismal denouement for a club that weathered the 1913 miners’ strike, the 1922 Rand Rebellion, the exodus of companies from the central business district in the 1980s, a fire in 2005, and Covid. And yet the Rand Club – from which Randlords plotted South Africa’s ascent to the top of the gold mining pile – may ultimately be undone by venal politicians, seeking to extract more than a pound of flesh.

A trail of documents obtained by Currency in recent weeks spells out how the city levied a sky-high value on the property of R23.8m – nearly three times the R8m value of just two years before – which appears vastly out of touch for one of the few remaining businesses in Joburg’s clapped-out CBD, from which nearly all companies have fled.

Nonetheless, based on this new supposed value, the cash-strapped city hiked the cost of its utilities to the club by more than 88%.

Brian McKechnie, a heritage architect and the chair of the club, says the city’s actions are tantamount to expropriation.

“The City of Johannesburg seems determined to put the final nail into the coffin of an institution that’s endured since the very beginning of Johannesburg,” he tells Currency.

McKechnie says the “massive” rates hike is not only completely out of touch with market realities, it is also a cost the club is “absolutely not” able to afford.

This revaluation means the Rand Club’s new monthly utility bill clocks in at R182,000, with rates alone having nearly doubled to R47,500, from R25,200 before.

To make it worse, the City of Joburg has now slapped the club with a backdated bill of R477,000, applied retrospectively to July 2023. And it wants R290,600 for outstanding water charges – though this was cut from R500,000 thanks to the City ombudsman.

Tightening fist

The Rand Club has been fighting overly-ambitious attempts by the City of Joburg to revalue it – and hence, extract more in levies – for years.

Back in 2018, and after much wrangling, the Rand Club and the city agreed on a value of R8m for the club. Then in 2023, despite the collapse of water and electricity in the area, the city suddenly ratcheted up the value to R13.2m.

The Rand Club appealed, with the club’s valuer (and former chair) Richard Currie arguing the value remain at R8m based on what it actually earned from events, rentals and member fees. “There is no justification for increasing this value considering the challenges property owners are facing in the CBD,” he wrote in a letter to the city.

Yet the city insisted – and from there, things unravelled even more spectacularly.

In December 2024, at the appeal hearing, Selby Sambo, an assistant manager in the city’s valuations office, said that, actually, the Rand Club’s value should be radically hiked to R23.8m, based on the hypothetical conversion of the building to commercial or residential accommodation.

That would be nearly double the R13.2m value of a year before, and 197% more than the R8m of 2018. The city, eager for cash, gladly accepted Sambo’s argument.

In that hearing, Sambo presented a convoluted argument for why the R8m value shouldn’t apply, saying that “on the little knowledge that I have”, the club shouldn’t be valued based on the amount it could earn. “In Johannesburg, we don’t determine the current use value; we determine the market value,” he said.

The problem is, the cratering of the city around the Rand Club contradicts Sambo’s ambitious claim.

In 2022, Aegis House, a 6,000m2 building opposite the Rand Club on Loveday Street, was sold for R12.27m. That building, Currie said, was three times the Rand Club’s size and had a design “allowing for easy conversion to residential units”.

In 2021, Victory House, 2,500m2 in size, was sold for R3.75m. And the old 7,000m2 Standard Bank building, on the corner of Simmonds and Commissioner streets, was sold for about R15m in 2022. The bank’s headquarters are now in Rosebank.

There were other problems with the city’s valuation.

For one thing, Currie said Selby’s valuation was marked by its “excessive concentration on the history of the building and the sociopolitical history of the club”.

This contradiction is clear: the city used a heritage methodology to justify a high valuation, yet it taxes the club like a full-blown commercial operation.

McKechnie says the decision to value the club on its heritage status – based on its replacement value, less depreciation – is useful for a structure where it is not possible to benchmark against similar sales, or where there is no way of calculating achievable income. But both of these are possible with the Rand Club.

“This approach is incorrect because, while the club is housed in an old building constructed in 1905, it is not formally declared as a heritage resource or heritage monument,” he says.

Currency sent questions to Nkosana Lekotjolo, a spokesperson for the city, as well as to the valuation appeals board; we are awaiting their response.

A cultural monument

Were the Rand Club to close, it would mark something of a metaphorical death knell for the inner city, and represent a blow to Joburg’s richly-textured history.

For much of its history, the wood-panelled, stained-glass-window-pocked building was a gentlemen’s-only club. But in the early 1990s, it opened to women and people of colour – and today, it is a very different institution.

Members are racially and generationally mixed. Presidents Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Cyril Ramaphosa were all members at one point. And a group of committed Joburgers have revived it pro bono, adding a business centre, a new members’ bar, and recurated the club’s art using pieces on loan from corporate collections.

The result is one of the few Joburg success stories in the inner city. Even the city’s current mayor, Dada Morero, regularly uses it for meetings – ironically, given that his office is the source of the club’s existential crisis.

But while the Rand Club’s glamour once matched its surroundings, this is no longer so. Over the past decade, the streets have become grimier; litter is piled against the pavements; and those companies that braved it out, hoping for the much-promised “inner city rejuvenation”, finally threw in the towel.

A hodgepodge of coalition governments – Joburg has had 11 mayors since 2016 – collapsing infrastructure, and little accountability for ineptitude at City Power and Joburg Water, have sapped confidence. The Rand Club just about held it together, but the city fell apart.

In the face of this, McKechnie says the club “overhauled” its operating model in 2017, but it has still been increasingly difficult to make a profit.

“While this new way of doing business has allowed us to retain our cherished home in the CBD, it is still an uphill battle. Certainly as long as I’ve been on the committee, we have been in a break-even position at best,” he says.

The Rand Club is still meeting its commitments to pay its 25 staff, its suppliers, and the city, for now. But there is little money left in the pot after that.

“Aspects like critical building maintenance have been deferred for decades, since there just isn’t money available to undertake these projects,” he says.

Oasis in a desert

If you’re looking for a sense of what the Rand Club is up against, consider the story of art curator Nkuli Nhleko Bernhardt, who went on her first date with her now-husband Andreas at the Rand Club in June 2022.

She says for her anniversary this year, “Andreas organised a night there again”. They ended up eating dinner in an almost empty club restaurant, and later, after they had gone to one of the suites, there was a knock on the door from the staff.

Nhleko Bernhardt says they were asked if they’d mind if the club turned off the generator, since they were the only guests that evening.

“There was no municipal power and so they bought us blankets and candles, and we spent the night like that. They switched the generator on again at 6am. It was strangely romantic, but also sad,” she says.

This wasn’t an isolated example. McKechnie says this part of the city regularly has no municipal water, which means the club cannot rent out rooms it revamped a few years ago.

While the club used to make R40,000 a month on the rooms, that is down to R10,000 thanks to the water crisis.

This scale of the challenges in the city suggest it is possible that even without the City of Joburg’s steep rate hikes, the Rand Club may have folded.

While the Rand Club hires out the space for movie shoots, weddings and functions, the growth in crime in the area has meant fewer people visit. And the security bill is footed by the club, not the city.

For McKechnie, this latest crisis only accentuates his sense of defeat.

This is an institution that “decided to remain on our corner of Fox and Loveday Street – not only as a reminder of how great Johannesburg once was, but as a beacon to the promise that the city could become something great again,” he says.

Yet if the club closes – a route now more likely thanks to the City – 33 Loveday will become just one more shuttered-up building, like most of its neighbours.

“This is the legacy that mayor Morero and his administration seem to be working towards,” says McKechnie. “A city of derelict, deserted old buildings and lost economic opportunities.”

Top image: The Rand Club, corner Commissioner and Loveday streets, Joburg.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Some may infer from the article that the city is undermining the monied class. However the city has heaped far more damage on those without means. Investment in state and privayte housing is at a all-time low. The number of indigent supported by the city is also at an all time low (about one-fifth that of Cape Town). I think is little doubt that Johannesburg needs to be rebranded from “a world class African city” to ” city at war with its residents”.

Tragic. If Helen come to run Jhb may I suggest that she make use of the Club for her War Room and conduct operations from there whilst she sorts out the Civic building fiasco which I suspect will be one of her many issues to address?

33 Loveday…. an add number, considering the street numbering, don’t you think? Note that there are also 33 degrees in Scottish Rite Masonry. And unfortunately, the club seems to be going the same way as Masonry. People just aren’t interested in doing the work it takes to be decent and “old money” these days i.e. having class, not flashing the cash, being a producer and not a consumer etc. Instead, everyone is too busy chasing the emptiness of their glass and chrome, plastic-filled, gilded cages. Greed and laziness are destroying our world, never mind just the Rand Club.

Such heritage sites need to be respected and ring-fenced from such bureaucratic greed. Time to start a petition.