There are some subjects South African Reserve Bank (SARB) deputy governor Fundi Tshazibana would rather avoid. Chief among them is why the monetary policy committee (MPC) announced it is aiming for 3% inflation before agreeing on a new target with the National Treasury.

While the SARB and Treasury are still working together on what the new target should be, finance minister Enoch Godongwana’s ministry will have the final say and set the mandate for the MPC to follow. The SARB then acts independently in ensuring the goal is met. For now, the official target remains a range of 3%-6%, though, for the past eight years, the MPC has aimed at the 4.5% midpoint.

Governor Lesetja Kganyago drew the ire of Godongwana when, after last month’s MPC meeting, he said the central bank prefers inflation at the bottom of the band. It immediately prompted a rebuke from the finance minister, who said the “unilateral” announcement pre-empted legitimate policy deliberations, which also include the cabinet and “relevant stakeholders”. Godongwana added there were no plans to announce a new inflation-targeting framework during October’s mid-term budget.

“The jury’s out on whether waiting was the right thing to do,” Tshazibana told Currency on the sidelines of a Nedbank conference this week. “Waiting would have been ideal, because then there would not be confusion between what is a preference and what is a target.”

But the monetary authorities would have missed another opportunity, she argues: to anchor inflation expectations around 3% when inflation is already hovering near that level. “It’s your assessment that we pre-empted [the Treasury],” she says. “It’s our assessment that, as a monetary policy committee, we have to be opportunistic in the way that we act, and we saw an opportunity here.”

Tshazibana says the SARB also wanted to minimise what it calls the “sacrifice ratio” – the economic pain in terms of lost growth that society must endure to bring inflation down to a lower target. “This is what we saw in 2017, when we said the anchor is now 4.5%. It happened at a time when inflation itself was coming down. The sacrifice ratio was almost non-existent because inflation itself was coming down.”

Balancing the books

Markets welcomed Kganyago’s announcement, which – strictly speaking – still falls within Treasury’s 3%-6% range adopted in 2000. Bond yields fell, pushing prices higher, as investors bet that lower inflation would eventually mean lower interest rates.

Casey Sprake, economist at Anchor Capital, points out that the Treasury’s hesitancy may reflect the “less-often acknowledged reality” that it has relied on inflation to “balance its books”.

In the latest budget, for example, Treasury again refrained from adjusting personal income tax brackets for inflation, boosting revenue through so-called fiscal drag as it attempts to contain rising debt that has seen debt-service costs consume roughly 22c of every rand in tax revenue.

“Lower inflation erodes the effectiveness of this approach,” she writes. Supporting a 3% target would therefore require downward revisions to both spending growth and revenue projections – an adjustment that will be politically difficult.

Treasury’s revenue projections are currently built on 4.5% inflation assumptions. If inflation falls to 3% while spending rises as though it were 4.5%, the fiscal balance could worsen, undermining credibility rather than restoring it, Sprake notes.

The SARB’s June models suggest that a 3% target would have implied the repo rate being 50 basis points (bp) lower in 2025 and up to 150bp lower in the longer term. Such a shift could gradually bring borrowing rates below 6%, rather than keeping them stuck above 7%.

Lower inflation would also reduce government debt-service costs, potentially saving R130bn in five years and up to R600bn by the end of the decade. “By lowering the inflation risk premium, borrowing costs on new debt issuance would steadily fall, providing much-needed fiscal space at a time when South Africa faces heavy refinancing pressures,” Sprake says.

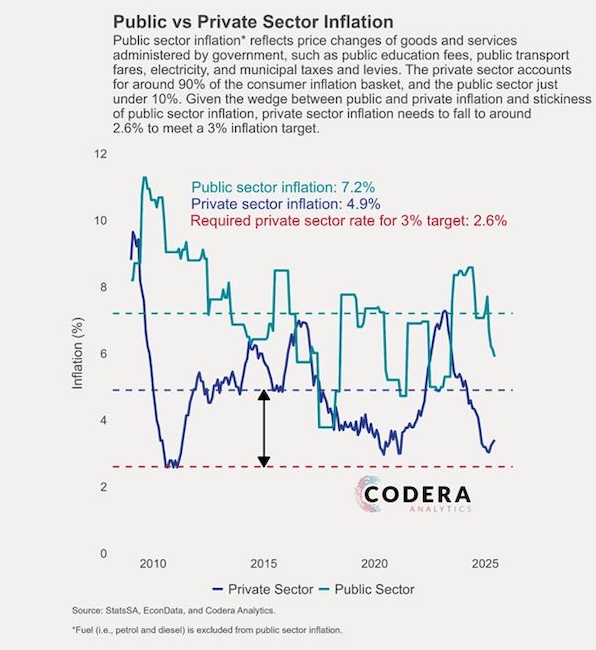

Yet there are snags. A significant share of South African inflation comes from government-administered prices – electricity tariffs, municipal charges, public wages – which consistently rise faster than the overall rate. Unless these are contained, the burden of hitting 3% would fall disproportionately on the private sector through higher interest rates, according to Codera Analytics.

In a paper released by Codera in February titled “Gaps in the South African Inflation Targeting Debate”, the authors argue that the SARB may be too optimistic and that disinflation costs could be higher than it suggests. Achieving lower inflation requires complementary fiscal policy, structural reforms, and co-ordination across government, regulators, state-owned enterprises and labour unions. There is also little empirical evidence on what level of inflation is optimal for South Africa.

The transition to a lower inflation target is not without risks, says Felicia Makondo, fund manager at PSG Asset Management. “To lower inflation, the MPC typically increases interest rates. South Africa is already grappling with weak GDP growth, supply-side bottlenecks and fragile consumer demand. High interest rates are likely to stifle already fragile growth even further in the short run.”

If expectations are not successfully lowered, the result could be more volatile inflation and a loss of credibility. Brazil is a case in point. It reduced its target from 4.5% to 3% between 2017 and 2021, making that level permanent in 2024. But fiscal dominance and political pressure undermined its central bank, and inflation expectations remained above target. Rather than boosting credibility, markets grew wary of the mismatch between the target and fiscal realities, Makondo notes.

For South Africa, the debate isn’t over. “You don’t have a Reserve Bank that has walked away and said, ‘Treasury, you run your own thing,’” Tshazibana says. “No. The work is still under way, and [the outcome of those] conversations is still unknown.”

Top image: SARB deputy governor Fundi Tshazibana. Picture: supplied.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.