For decades, executives have been paid a king’s ransom in the expectation they will generate huge wealth for their shareholders.

It seemed an obvious assumption. We (the shareholders, goaded by remuneration committees who always warn about the need for benchmarking) will pay you (the executives) enormous remuneration packages and you will deliver huge profits.

Well, it turns out things aren’t quite that straightforward. In fact, it turns out, you can heap all sorts of generosity on your executives and, for the most part, have no certainty on how effective they will be in generating profits.

It is, overwhelmingly, a random exercise.

And as long-term data compiled by trade union-aligned think-tank Labour Research Service (LRS) reveals, the exercise is made no less random by throwing long-term incentives into the pot. As the LRS sees it, no amount of guaranteed pay, bonuses and incentives ensure profit performance.

It’s not just that executives extract huge sums for poor or indifferent results. In some instances where profit performance has been consistently bad for a few years, the remuneration committee often responds by paying its executives more.

How it works is this: the executive responsible for the poor results sidles off into the horizon with enough money never to have to worry about working again. (What about the malus and clawback provisions, I hear you say. Turns out that is just a gimmick to placate the supine institutional fund managers who are enabling the process. Had he lived, it’s extremely unlikely even Markus Jooste would have had to pay back a cent).

After years of grim performance, the remco decides the one assured way to stop the rot is to get a new CEO. The replacement CEO will have to be given a massively generous package (think Woolworths’ Roy Bagattini) to lure him to a company that doesn’t have a sparkling recent history. Additional money will also be needed to replace the huge dollops of share options the new executive is leaving behind in his inevitably more secure employment.

The result is that a poorly performing company is forced to pay even more ridiculous amounts of remuneration in the desperate hope it will solve their performance problems. Often it doesn’t.

In Woolworths’ case, Bagattini’s reign did coincide with an initial bump in results. The bump was long enough for him to collect a massive payout on his early-awarded options. Unfortunately, right now it’s not looking like such a rock-solid recovery.

The reality is the primary explanation for excessively generous executive remuneration packages is that executives control the purse strings. And despite all that governance guff about independent boards, none has proven independent enough to say “no” or even “perhaps not so much” to their grabby, entitled executives.

Sure, remcos do put a lot of effort into aligning pay with performance. They do this by promising to reward the executive a chunk of cash and lots of shares if they reach certain predetermined targets. However, apart from a few glitches over the Covid period, there are few known instances of executives not getting paid out their short- and/or long-term bonuses – even in years when profit performance was sketchy.

Extremely random

So, just how random is the remuneration process? Well, a recently released report compiled by LRS in conjunction with Active Shareholder, a not-for-profit company that helps investors exercise their company rights, suggests it’s extremely random.

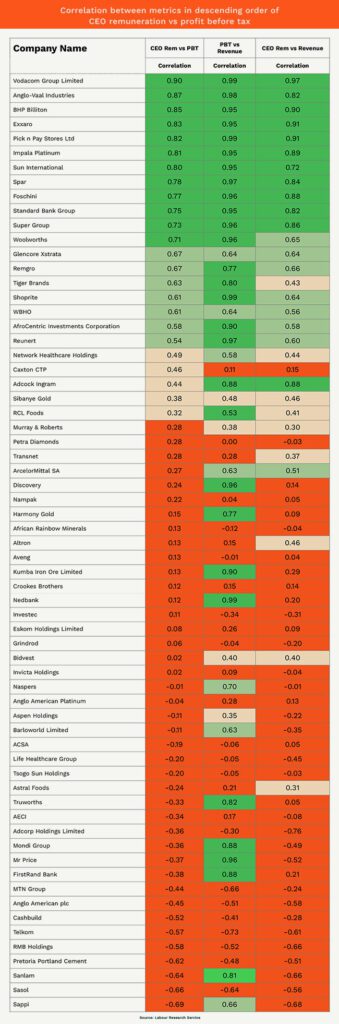

The LRS’s Salomé Teuteberg and Active Shareholders’ Rod Bulman pored over 10 years of data for 65 of the largest companies listed on the JSE trying to establish a link between CEO remuneration and profit performance. “Our results showed no clear pattern,” Bulman tells Currency.

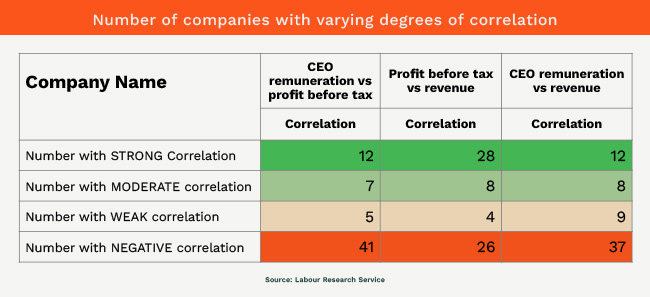

He and Teuteberg studied financial data from the 65 companies for the years 2014-2023. Only 12 of the companies showed a strong correlation between CEO remuneration and pre-tax profit over the decade. In other words, in only 18% of companies did the remuneration policy actually achieve what was intended. That is, CEOs were well rewarded when the company performed well, but did not receive overly generous rewards when results were poor.

A further seven companies demonstrated a moderate correlation between CEO remuneration and pre-tax profit; five demonstrated a weak correlation; and, for a troubling 41 – that’s a full 63% of the companies studied – there was a negative correlation between remuneration and pre-tax profit.

A negative correlation in this case essentially means that the rate of change in remuneration was going in one direction while the rate of change in pre-tax profit was going in the other.

The list of companies with strong correlation includes Vodacom, AVI, Pick n Pay, Sun International, Spar, Foschini, Standard Bank and Woolworths.

Remgro, Tiger Brands and Shoprite demonstrated moderate correlation.

But some of the most august companies on the JSE – like Sanlam, Sasol, Anglo American and Naspers – were in negative territory. (See the table at the end of the story for more.)

Strong correlation doesn’t necessarily mean shareholders are getting value for their money (nor does it imply cause or effect) but at least pay is going in the same direction as pre-tax profit.

Consider Vodacom. Back in 2015 the CEO took a 15% hit to his remuneration, which coincided with a 9% drop in pre-tax profit. However, in 2016 his remuneration more than doubled to R35.5m despite only bumping up profits by 5.56%. Things settled down a good bit after that, though it’s important to note that from 2017 the CEO was working from a considerably higher remuneration level.

Pick n Pay’s CEO remuneration was all over the place – almost doubling some years, cut by more than a third in others. This is what you’d expect with a company whose profits were also exceptionally volatile. Of course, at no stage, even when a hefty loss was reported, was the CEO not paid.

The LRS’s painstakingly gathered data – it’s an enormous treasure trove of information – should be required reading for anyone concerned about the ever-widening gulf between executives and ordinary workers, says Bulman. It provides a much broader context for deciding whether shareholders are actually getting value for their money.

Remuneration reports and policies are based on hope for the coming years, and the LRS data reveals how ill-placed this hope often is.

It would do no harm for institutional investors to take a look at the data. At the very least, it will encourage them to challenge the crass assumption underpinning runaway executive pay; namely, that CEOs have to be paid ridiculous sums of money or the profits won’t materialise.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Stunning – and yet, will the trends ever be reversed? Crony Capitalism at it’s finest – if the CEOs actually had their own skin in the game as opposed to that of their shareholders’ it MIGHT justify their pay packages. But I doubt it. I could easily do a far better job than anyone of them – consider that a challenge issued.

For 1/10th of their nett package. Challenge updated.