Investment from the Middle East into Africa is catching fire, as countries from the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) push forward with long-term efforts to diversify their economies outside of oil and gas, somewhat making up for huge reductions in the US aid budget.

The Middle East, particularly GCC countries, has dramatically intensified its investment activities in Africa over the past few years, signalling the emergence of a new player in what is already a crowded field for a relatively modest asset base.

Fortune magazine recently reported that in the past 10 years the GCC – comprising Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman – has invested more than $100bn in Africa, with momentum accelerating significantly. In 2023 alone, Gulf states made investment pledges worth more than $53bn – almost four times the amount invested by US-based companies. With China and Russia also keen to expand their African investment portfolios, the GCC expansion comes at the time of heightened geopolitical stress.

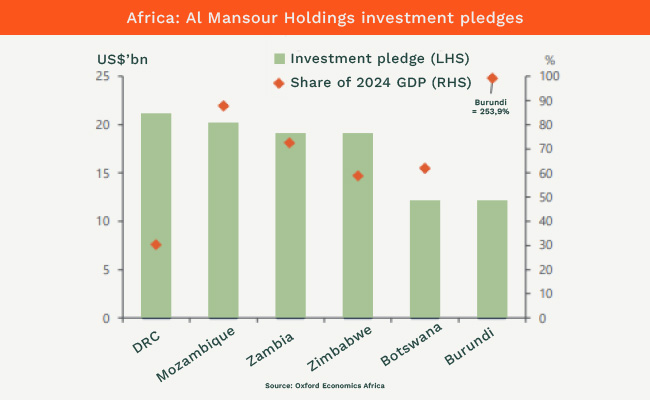

The emergence of the GCC investment has in some cases been very dramatic. A good example, according to Oxford Economics economist Brendon Verster is the decision by Qatar’s Al Mansour Holdings to pledge investments totalling “a staggering $103bn across Africa”.

Verster says research organisation Africa Business+ and accounting firm EY reported that investments from GCC countries in critical minerals assets in Africa totalled a hefty $2.2bn in the first half of 2025.

Some of the notable deals include the UAE’s Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company investment into Egypt’s Ras El-Hekma peninsula development project, which lifted foreign direct investment (FDI) in North Africa by a staggering 227% in 2024.

Meanwhile the UAE has also become one of Africa’s largest maritime partners, with DP World and AD Ports Group funding and managing port infrastructure across the continent. DP World runs Berbera Port in Somaliland, the port of Dakar in Senegal, container terminals in Ain Sokhna Port in Egypt and the port of Maputo in Mozambique.

Mining assets have been an obvious target. Gulf states are targeting critical minerals (like copper, cobalt, lithium) through state-backed entities like Saudi Arabia’s Ma’aden and Qatar Investment Authority, often via joint ventures, Sharia-compliant financing, and infrastructure-for-minerals deals.

Last year, Saudi Arabia signed deals with four African countries (details not specified, but likely including Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo) for critical minerals exploration. Ma’aden and the Public Investment Fund are pursuing copper and other minerals.

In October 2024, Saudi Arabia committed $41bn over 10 years to Sub-Saharan Africa, targeting industry, mining and energy.

Abu Dhabi’s International Resources Holding paid $1.1bn for the Mopani copper mine in Zambia last year and has invested more capital in the site since then.

But mining is only one sector benefiting from Middle East interest: the other is agriculture, partly to ensure Middle Eastern food security. Earlier this year, Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Company acquired a 35.43% stake in Olam Agri Holdings for $1.24bn.

Telecoms has been a long-standing sector of Middle Eastern interest in Africa, but other sectors like real estate and transport have also seen recent investment.

FDI on the rebound

For Africa, these inflows contributed to an FDI rebound to $97bn in 2024 (up 75% from 2023), with GCC capital filling gaps left by China’s slowdown.

China has been until recently one of the main drivers of African FDI, but according to an Oxford Economics report, China’s stock has remained relatively stable since 2017. China’s interest has expanded from extractive industries into manufacturing, logistics and battery‑metal projects, giving Beijing influence over trade routes and industrial policy, the report says.

To some extent, the inflow has geopolitical dimensions: Gulf states are competing for influence, especially in the Horn of Africa (for example, UAE/Saudi in Djibouti/Somalia for Red Sea security). The “Gulf scramble” mirrors past powers but tends to emphasise mutual benefits like ESG standards and local processing.

It’s not clear, says Verster, how conditional any of these investments are, but in the light of the need for Africa to wean itself off aid financing towards real industrial investment, they are welcome.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.