In a momentous shake-up for the gold industry, the leadership of the world’s two largest gold companies – Newmont and Barrick – have changed on the same day. The circumstances couldn’t be more different. Yet both take place against the background of an absolutely rampant gold price, whose wild bonsella has almost certainly played a part in the leadership changes.

Comparatively, the more measured succession is taking place at the larger of the two companies, Newmont, which announced on Monday that CEO Tom Palmer would step down at the end of the year after six years at the helm.

His successor is chief operating officer Natascha Viljoen, a widely-anticipated replacement since Viljoen joined Newmont three years ago following a very successful stint as CEO of Anglo American Platinum (now Valterra Platinum), where she was credited with dramatically improving operations.

Anticipated or not, it’s still a remarkable achievement for a youngish woman from Klerksdorp, whose father was a cage winding engine operator, to find herself at the absolute pinnacle of the gold mining industry.

For those carrying the South African flag, the rest of the news is not so great. That is, the sudden departure of Barrick CEO Mark Bristow, one of South Africa’s most high-profile and outspoken CEOs in the mining business, after seven years in the top job.

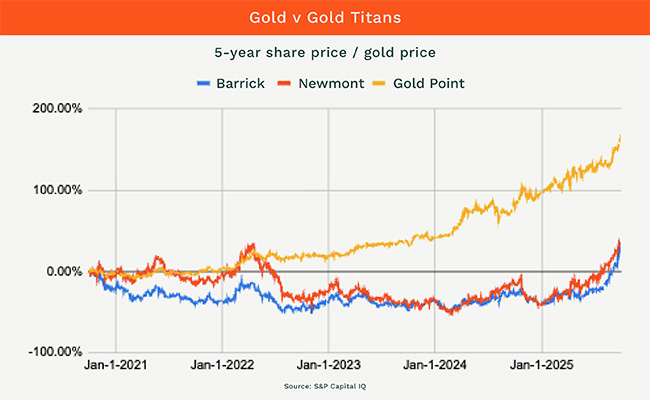

Arguably, both companies’ strategies need to seen in light of how their shares have performed since gold began its momentous run. Barrick’s stock is up 23% over the past five years, while Newmont’s is up 33%. That’s okay, but it’s easy to imagine some very intense shareholder frustration behind the scenes, as the gold price has almost doubled over the same period.

The reasons for the disparity between their share prices and the gold price also differ between the two companies. Newmont’s approach to the rising share price has been to aggressively go shopping. For starters, it splashed out $10bn on Canadian mining company Goldcorp in 2019. Apparently not satisfied with that mega-deal, it then bought Newcrest for $16.8bn in 2023.

Barrick’s trajectory has been much more complicated, though arguably it started the merger mania when it bought Randgold Resources, the gold company founded and run by Bristow, in 2018 for $6.5bn. The deal was orchestrated by Barrick executive chair John Thornton, who remained executive chair of the merged company and who is probably the most instrumental in elbowing Bristow out.

It’s well known that Thornton wanted a more aggressive acquisition strategy; he said as much at the London Indaba last year, when he told chair Bernard Swanepoel in a Q&A session that the company had been too reticent in merger and acquisition dealmaking.

“Barrick has been, in my view, very slow to say to themselves: the most important thing when you’re buying companies in the mining industry … is just buy it. We have not done that. We have insisted on getting into the weeds and that’s been a mistake.”

(Incidentally, Thornton told the same gathering that: “When you’re dealing with a sovereign entity whether it’s Tanzania or any other country: guess what, they own the asset; it’s theirs, they’re bigger than you are, more powerful than you are, they write the rules, they can change the rules and if that partner’s not happy you’ve got a big problem. But the truth is, most mining companies don’t do it very well.”)

Reflecting on Bristow’s shock exit, one mining veteran says: “I think the dynamic is that when you’re the chair of a high-profile company and your share price underperforms, it’s amazing how egos come into play. I’m only surprised that those two egos lasted as long as they did in one boardroom.”

The Africa equation

Bristow’s dilemma was essentially that the African businesses in Tanzania and Mali that he brought into the merged company had gone spectacularly wrong. Bristow’s implicit value was that he knew how to operate in Africa’s wildly tricky mining context – utility that was dramatically upended with the disaster in Mali.

In January last year Mali’s new military government seized about three metric tons of gold stored at the Loulo-Gounkoto complex and blocked exports, which triggered Barrick’s suspension of operations. In response, Malian military helicopters landed at the complex and airlifted more than one metric ton of gold from the site, forcing Barrick to take a $1.04bn write-down linked to the Loulo-Gounkoto complex.

According to Reuters, Barrick’s entire future in Mali is now uncertain, as the company’s mining license comes up for renewal in February 2026 – and if it can’t reach a deal with the government it may lose its asset entirely.

“Remember that Africa was Mark Bristow’s claim to fame. Randgold Resources was the ultimate African story and Mark knew the place better than anybody; he knew where a gold orebody was; he could handle the risk and so I think these are factors conspiring against him. The company isn’t doing well and his baby is the problem child,” one source tells Currency.

“Everybody else in Mali rolled over and accepted that the government wanted more and he decided to die on that hill,” says the source, comparing it to the first round of the mining charter in South Africa, where the companies that refused to accede to the government’s new mining laws simply left.

The disaster has also complicated the company’s acquisition programme. One mining expert Currency spoke to commented that the problem with gold acquisitions is that they are normally overvalued, which means unless the acquirer’s stock is equally overvalued, the acquisition tends to end up being value destructive.

From Bristow’s point of view, the timing for the company to engage in large-scale M&A was not great, particularly as it has two large gold projects under way in Pakistan and the US which have yet to make an impact on the company’s profits. As a geologist, Bristow is anyway better known for his achievements in exploration and as a mine developer than as an acquirer.

But was Bristow right to dig in his heels in refusing to make acquisitions as the gold price started to run?

Asked about this, Swanepoel, chair of the Junior Indaba and former Harmony Gold CEO, tells Currency: “I don’t necessarily buy into the narrative that there would have been pressure on Mark to do M&A now. Perhaps the criticism was that in the past, when he could have and should have, he didn’t. But right now you can only overpay for gold assets. This is the crap of the cycle: you buy at the bottom and sell at the top, but if only we knew when the bottom and top was.”

Top image: Mark Bristow. Picture: Gallo Images/Business Day/Trevor Samson; Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.