Now that the US African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) has formally expired, attention is likely to turn to intra-African trade as an alternative. So how is that working out?

For Wamkele Mene, secretary-general of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the threat of high tariffs with the US represented both crisis and opportunity. His comments sparked renewed debate about whether mounting global protectionism might finally catalyse the continental trade integration that has remained frustratingly elusive since AfCFTA’s 2021 launch.

Yet a new analysis from Oxford Economics Africa suggests that optimism may be premature. Despite the theoretical appeal of redirecting trade inwards amid a fragmenting global order, the structural impediments to African integration run deeper than tariff schedules and political declarations, a new report from the research organisation says.

The American mirage

The case for pivoting away from US markets appears straightforward on paper. Africa’s exports to America rose modestly from $22.6bn in 2000 to $33.7bn in 2024, but their share of the continent’s total exports plummeted from 15% to just 4.9% over the same period.

“Mene said that the measures imposed by the US should serve as a wake-up call for African governments to fast-track regional trade integration and build self-sufficiency,” the Oxford Economics report, written by senior economist Pieter du Preez and political analyst Jervin Naidoo, notes. But this narrative confronts an inconvenient reality: the goods Africa exports to the US – predominantly mineral fuels, oils, natural pearls and raw commodities – are largely exempt from tariffs even in the post-Agoa period and reflect the continent’s persistent inability to move up the value chain.

More troubling still, Africa remains trapped in what economists call the “round-tripping model,” exporting raw materials while importing manufactured goods. Even where import substitution appears feasible – Africa imports substantial quantities of mineral fuels and vehicles, goods it also exports – the underlying dynamics reveal manufacturing weakness rather than opportunity. African nations lack the industrial capacity to process their own raw materials or produce finished vehicles at scale.

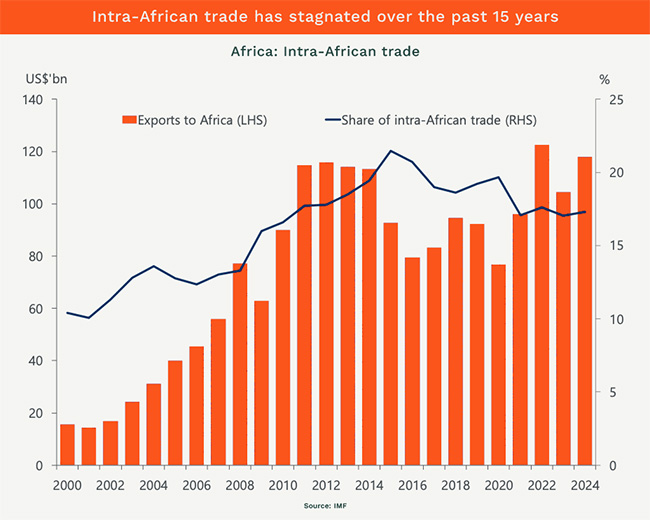

Four years after the AfCFTA’s official implementation, the trade data tells a sobering story. Intra-African trade stood at 17.3% of total continental trade in 2024, barely changed from the 17.1% recorded when the agreement launched in 2021. This stagnation becomes more striking when compared to intraregional trade in Asia (more than 50%) or Europe (about 70%).

The absolute value of intracontinental trade did grow from $16bn in 2000 to $118bn in 2024, but as a share of total trade, it peaked at 21.5% in 2015 and has declined since. “It is safe to say that, as of 2024, AfCFTA has not led to an increase in intracontinental trade,” the Oxford Economics report concludes.

While 54 countries have signed the agreement – only Eritrea remains outside – just 48 have deposited ratification instruments. Libya, South Sudan, Madagascar, Somalia and Sudan have yet to complete this crucial step, underscoring the gap between diplomatic commitment and operational reality.

The infrastructure deficit

Behind the disappointing trade figures lies a web of practical impediments that no agreement can wish away. The African Development Bank estimates that addressing the continent’s infrastructural deficits requires annual investment of between $130bn and $170bn. Currently, roughly 77% of Africa’s freight moves by road, while a mere 0.3% travels by rail – a striking imbalance in a continent where rail freight costs half that of road transport.

As XA Global Trade Advisors has previously observed: “We have seen Chinese rail operators pulling back from operations across Africa. Rail is half the cost of road freight but still five times more expensive than maritime shipping. We are watching the rail freight business model evolve but we still have a long way to go.”

The result is a perverse economic reality: importing from Europe or China can prove cheaper and easier than sourcing goods from neighbouring African countries. Poor road networks, inadequate port facilities and fragmented air connectivity create bottlenecks that paper agreements cannot overcome.

But the real problem, says XA director Donald MacKay, is that Africa doesn’t buy the same stuff the US does and when they do overlap, the continent can’t compete with countries like China or India.

Political realities and border politics

Beyond infrastructure, political obstacles loom large. Africa’s colonial-era borders, which carved through ethnic groups, cultural zones and traditional trade networks, have bequeathed a legacy of mistrust and territorial disputes. Governments routinely assert sovereignty through heavy customs checks, disguised tariffs or outright border closures – measures often designed to appease domestic constituencies fearful of external competition.

Nigeria’s 2019-2020 border shutdown exemplifies these dynamics. Ostensibly aimed at combating smuggling, the closure functioned primarily to shield local producers from competition, illustrating how quickly integration ambitions collapse when confronted with national political imperatives.

Security challenges compound these difficulties. In the Sahel, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and the Horn of Africa, violent conflict regularly disrupts commercial corridors. Smuggling networks overlap with insurgent groups, while terrorism and trafficking concerns incentivise states to restrict rather than facilitate cross-border flows. The trade-offs are stark: the AfCFTA requires freer movement of goods and people, but regional insecurity pushes governments towards tighter controls.

Perhaps most fundamentally, the AfCFTA demands that member states align trade rules and cede authority to supranational bodies – a prospect that sits uneasily with leaders who have historically guarded sovereignty jealously. This reluctance extends beyond elite preferences to reflect genuine public anxieties. Farmers and labour unions fear being undercut by cheaper imports, while high unemployment and inequality can inflame xenophobic sentiment, particularly in countries facing economic strain.

“Political leaders, wary of this, often slow-roll implementation, prioritising domestic legitimacy over free-trade goals,” the report observes. The rise of non-tariff barriers – import licensing requirements, quotas, bureaucratic delays – means that even where formal tariffs have been lowered under the AfCFTA, market access remains constrained.

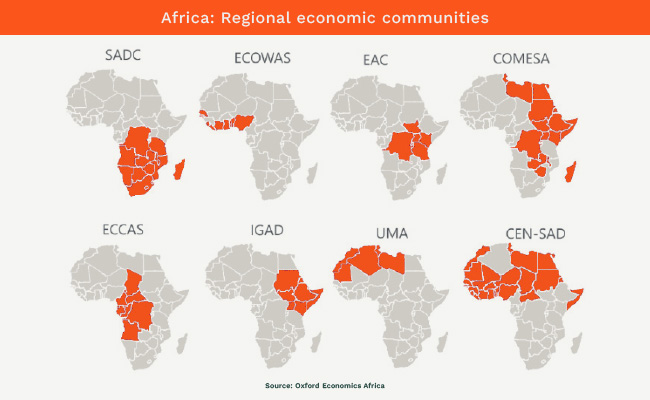

The continent’s patchwork of eight major regional economic communities, each with distinct rules, further complicates integration. While the AfCFTA was designed to recognise these existing blocs as building blocks rather than replace them, the overlapping memberships and competing regulations create confusion. Countries are likely to remain more loyal to established regional arrangements than to an unproven continental framework.

Glimmers of progress

Not all developments paint a bleak picture. Several institutions have been established, including the AfCFTA Secretariat in Accra, Ghana, and the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, designed to facilitate cross-border trade in local currencies. The Guided Trade Initiative, launched in 2022 with eight countries, has expanded to include 24 nations in 2025, suggesting incremental progress.

Countries like Rwanda and Ghana have eased visa restrictions in line with AfCFTA’s free movement principles, making intra-African travel simpler. These steps, while modest, demonstrate that implementation need not be uniformly stalled.

The path forward

The Oxford Economics analysis concludes that while the narrative linking global protectionism to African integration opportunities contains validity, “several critical issues still need to be addressed before AfCFTA can really take off”. These include infrastructure investment, industrial capacity development, logistics improvement and bureaucratic streamlining.

Most challenging may be the political dimension. “For AfCFTA to realise its potential, countries need to set aside their national interests, which is a considerable challenge in itself,” the report notes. Beyond signing agreements, nations must demonstrate genuine commitment to making the AfCFTA a meaningful driver of intra-African trade.

As global trade fragments and protectionism rises, Africa faces a genuine inflection point. Whether the continent can leverage this moment to build the self-sustaining internal trade bloc that has eluded it for decades remains an open question – one that will be answered not by declarations and summits, but by the unglamorous work of building roads, harmonising regulations, and convincing sceptical publics that integration serves their interests.

The opportunity exists. Whether the political will and practical capacity to seize it can be mobilised is another matter entirely.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.