There are some artworks that make you stand very still out of pure intrigue and fascination. Gerhard Marx’s pieces are among them. His new exhibition, Landscape Would Be the Wrong Word, at Everard Read Johannesburg, is a smart, quietly dazzling example of this.

The pieces are painstakingly structured, yet they pulse with life. They’re made of maps, plants, and even casts of Karoo ground, but they appear as portals – layered, shifting, almost alive. You feel you could reach forward and step inside them; rotate them; inhabit them (like something out of a retro computer game, if you remember the reference). Each one feels like a fragment of another realm being created right in front of you.

Marx, who began his career in Joburg but is now a consummate Capetonian, is undoubtedly one of South Africa’s finest contemporary artists. Many will remember his monumental 2013 work Vertical Aerial – the massive mosaic reconstruction of an aerial photograph of the Joburg CBD, composed of thousands of fragments of stone. It remains one of the most ambitious and poetic artworks to come out of this city: a literal mapping of place that more than hinted at his lifelong fascination with how we see, name and order the world. Like that showstopper, his new works are, at their heart, a commentary on the world we already inhabit.

The title itself is both a refusal and a provocation. He laughed as he explained it: traditional landscape implies distance – a viewer gazing out at the horizon, separate from what they see; his works collapse that space entirely. “Instead of making a landscape,” he explained, “I’m making a place.”

That idea – of place rather than landscape – has stayed with me. It’s a reimagining not just of what we look at, but how we look at it, and how we interpret that. His pieces pull you in, envelop you. They don’t want you to observe; they want you to linger, to dwell, to feel.

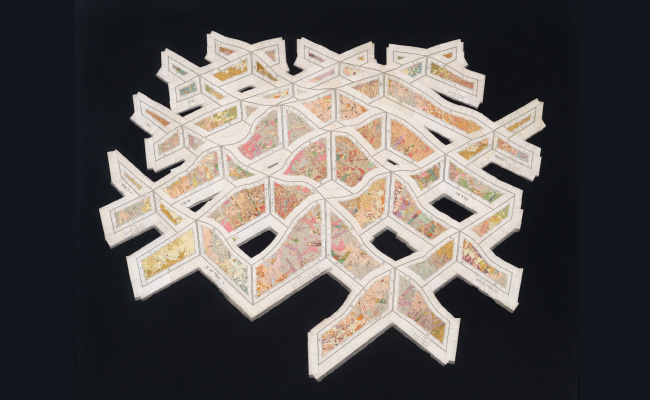

Marx has long been drawn to maps. He’s got a storeroom filled with old maps and they are a constant source of inspiration. He’s fascinated by the way they promise neat categorisation and project authority while quietly shaping how we see the world. In his hands, maps are taken apart, folded, cut and reassembled until they form complex geometries. What was once a fixed representation becomes fluid, uncertain, alive. “I’m always trying to write the subjective back into the supposedly objective,” he told me. “To take something that’s meant to be neutral, and make it personal again.”

It’s this kind of thinking that makes Marx such a compelling artist. His practise is both rigorous and deeply poetic. In Landscape Would Be the Wrong Word, he pushes that duality further, blending the scientific with the conceptual, the tactile, even the beautiful.

‘Drawing the world with the world’

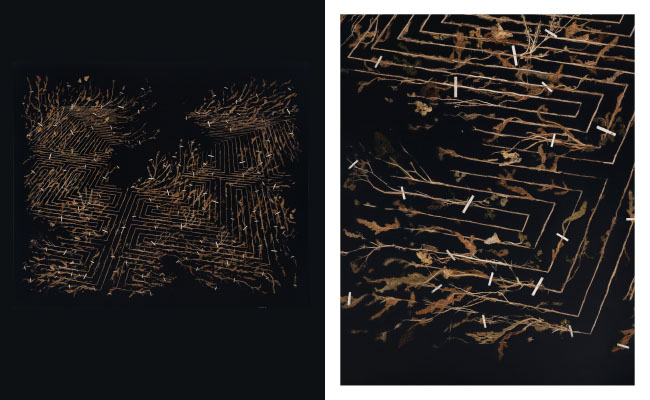

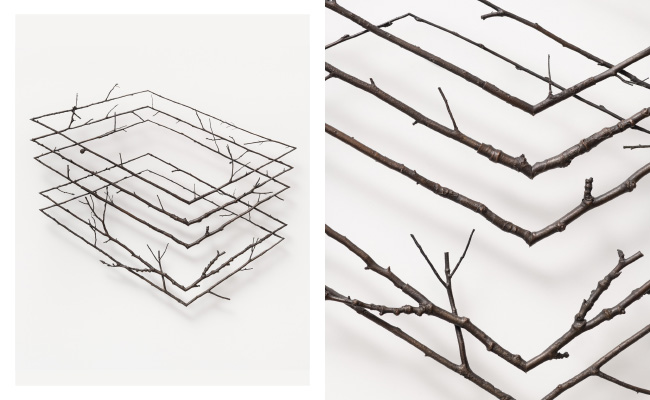

Alongside the map-based works are extraordinary “drawings” made from plants. He collects dried stems, leaves and flowers, often from the roadside, and painstakingly glues, sands and burnishes them into delicate surfaces. Nasturtium stalks, hydrangea heads, poppy stems – all become his materials. “When I draw with plants,” he said, “I am drawing the world with the world.”

The line perfectly captures the elegance of what he’s doing. It’s also a statement about humility – a recognition that the artist is not above nature but in dialogue with it.

The results are astonishing. The plant works are intricate, rhythmic and surprising too. Children, he told me with a laugh, often spot hidden birds or faces among the patterns before adults do. “There’s something in that kind of looking,” he said – “soft fascination”, he called it. That gentle curiosity, the act of noticing, is what these works demand.

Then there are the bronzes. In a series titled Unfolding Horizons, Marx cast panels directly from the surface of the Karoo – literal impressions of the ground. He has framed sections of untouched soil, created silicone moulds, and translated them into bronze. These are not depictions of the earth; they are pieces of it. “It’s about contact,” he said. “Not representation – contact.” They are geometric and textured objects that shimmer between sculpture and landscape, presence and memory.

If all this sounds too cerebral, it’s not. That’s the thing about Marx – he is an intellectual, yes, but he’s also a sensualist. His works appeal as much to instinct as to intellect. You feel them before you fully understand them.

As I listened to him speak, I was struck by how his way of “retranslating” the world – taking it apart and rebuilding it – mirrors what great writers do. I told him as much, mentioning Joburg’s literary treasure Ivan Vladislavić, who has made an art of rearranging language and urban space (Joburg in particular) to reveal their hidden magic. Marx’s eyes lit up: “I love Ivan,” he said immediately. Of course he does. They share the same compulsion to reorder, to find beauty and meaning in the overlooked, to make the familiar strange again.

It’s this quality – the ability to make us look differently, to reconsider what we thought we knew – that makes Landscape Would Be the Wrong Word one of the best art exhibitions that Joburg has glimpsed this year.

Standing among the works at Everard Read, you sense that Marx has built a universe of his own – one where maps bend, plants draw and the ground itself becomes an image. His art is a reminder that there are always other ways to see, other ways to describe, other worlds waiting to be made.

‘Landscape Would Be the Wrong Word’ runs at Everard Read Johannesburg until November 1.

Top image: Mercurial Map detail. Picture: Mike Hall.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.