Only 10 of 29 countries improved their overall score in Absa’s in-depth annual Africa financial markets index 2025, though the report does reflect steady transformation underpinned by reform, innovation and a deepening maturity in African capital markets despite global shocks.

The index is an annual X-ray of the continent’s economic bones, showing a body battered by global headwinds but with a surprisingly strong heartbeat.

It underscores a world in flux, focusing on trade frictions, tightening liquidity and sharp policy pivots from Washington to Beijing. Within that backdrop, Africa’s financial ecosystems showed both vulnerability and resolve.

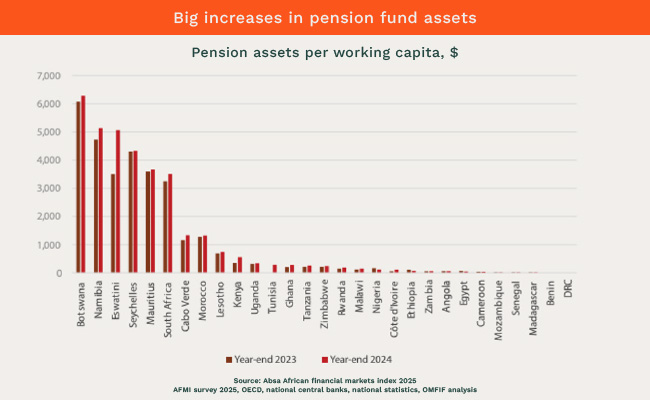

The comprehensive report measures six pillars: market depth; access to foreign exchange; transparency, tax and regulation; pension fund development; macroeconomics; and legal standards and enforceability.

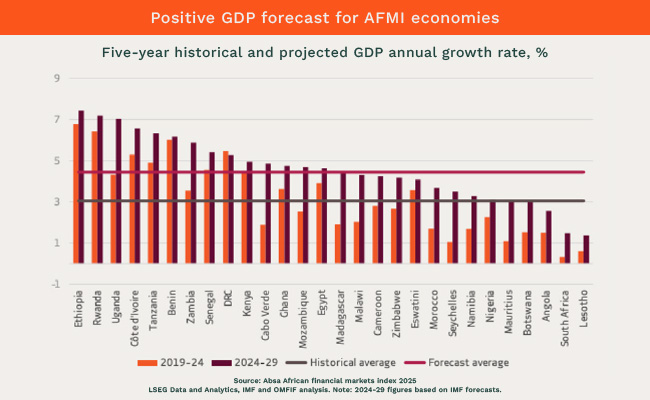

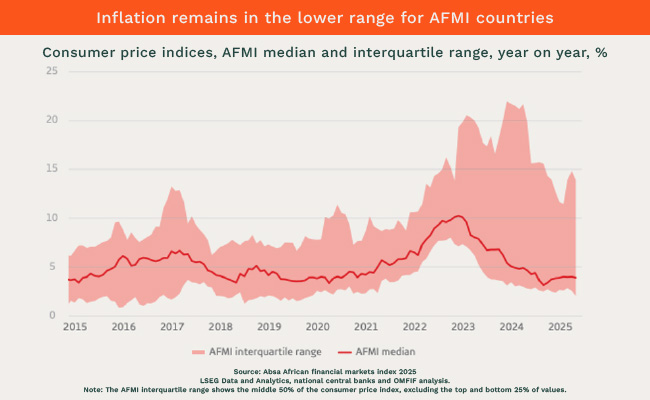

Of these, the report was most positive about the macroeconomic situation, suggesting economic growth well above the international average and inflation under control in most countries.

For the first time in years, more African economies are forecasting GDP growth above 5% than below it. Ethiopia leads the pack with 7.4% annual growth projected over the next five years.

Yet, even while inflation has dropped in 22 countries and external debt-to-GDP ratios improved in 16, the structural picture remains fragile. Three countries – Ethiopia, Ghana and Zambia – remain in debt distress, with five more at high risk.

On the other side of the spectrum, Botswana, Uganda and Tanzania share the top macro-transparency score (85), reflecting disciplined policy environments.

The financial data is complemented with a survey and, according to responses, the three main economic opportunities are in agriculture and agribusiness, renewable energy and energy transition, and digitalisation and financial innovation. These sectors can help to drive new financial products, like green bonds to support renewable energy, agri-SMEs tapping SME exchanges and fintech initial public offerings driving equity markets.

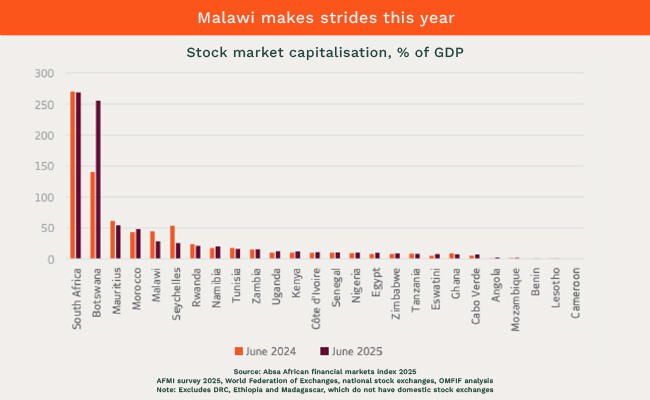

The weakest part of the report was the first “pillar”: market depth. This fell in more than half the countries surveyed, yet the narrative is not of retreat but recalibration. Sixteen of 29 markets saw reduced liquidity or market size, reflecting a tough global funding environment. Nonetheless, Malawi, Namibia and Botswana demonstrated reform-led gains. Malawi’s score surged nine points on the back of new bond incubation programmes and product diversification, while Namibia’s leap into the top 10 came via a new central securities depository.

The size of some countries’ equity market capitalisation compared to GDP remains extraordinary. South Africa’s equity capitalisation remains nearly three times GDP, while bond turnover of $2.7-trillion dwarfs the regional average of $95bn. By contrast, smaller economies like Ghana and Nigeria have battled liquidity constraints following domestic debt restructuring and forex reforms that initially curbed secondary trading.

The most dynamic story in this year’s report is told in pillar 2: access to foreign exchange. Here, reform has clearly paid dividends. Nigeria, long the poster child for forex dysfunction, leapt 21 points to rank fourth overall, after unifying multiple forex windows, clearing a $7bn backlog and phasing out distortionary interventions. Uganda also advanced, improving interbank liquidity and transparency.

Reserve adequacy, a crucial buffer, remains patchy. While Mauritius holds 11.8 months of import cover, Ghana has doubled its reserves to 3.6 months – a remarkable turnaround post-International Monetary Fund programme – whereas Botswana, suffering strain from a sharp drop in diamond revenues, saw its score collapse by 31 points. On average, countries in the index hold 4.4 months’ reserves, barely above the prudential minimum.

Interestingly, a quiet structural shift is under way: more central banks are diversifying reserves into China’s renminbi. Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda and South Africa have signed swap agreements, signalling a gradual erosion of dollar hegemony. Yet, as the report warns, without transparent reporting and deeper liquidity, “renminbi adoption remains a double-edged sword”.

If the forex chapter was about stabilisation, pillar 3 – transparency, tax and regulation – suggests some modernisation. Across the continent, ESG finance is no longer rhetorical. Fourteen countries have now issued green or sustainability bonds. Egypt’s introduction of Africa’s first regulated voluntary carbon market and South Africa’s climate stress test of six systemically important banks exemplify institutional seriousness.

Botswana’s stock exchange launched a sustainable bonds segment and discounted listing fees by 25%, aligning with global ESG disclosure norms.

Legal frameworks, long Africa’s achilles heel, are strengthening too. Mauritius and South Africa share a perfect 100 in pillar 6 – legal standards and enforceability – with Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda close behind at 90.

For investors, the data suggests a continent bifurcating between reformers and laggards. Countries like Nigeria, Uganda, Ghana, Namibia and Malawi are re-engineering their markets, while others stagnate under illiquidity and weak legal enforcement. The overall message is less about headline scores and more about direction: reforms work.

Africa’s story in 2025 is one of pragmatic optimism. The region’s combined GDP is projected to grow robustly over the next five years, driven by infrastructure investment and a deepening of capital markets.

The old binary of “frontier equals fragile” is breaking down. The countries that reform, like Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda, Namibia and Malawi, are creating investable stories. Those that don’t, like Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Madagascar, risk drifting into irrelevance.

As Jeff Gable, Absa’s chief economist, notes: “Success will come when African savings, formal or otherwise, join forces with global financing to deliver sustainable growth at competitive rates.”

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.