Finance minister Enoch Godongwana delivers his medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) on Wednesday in what will be the first true test of fiscal cohesion under the government of national unity (GNU).

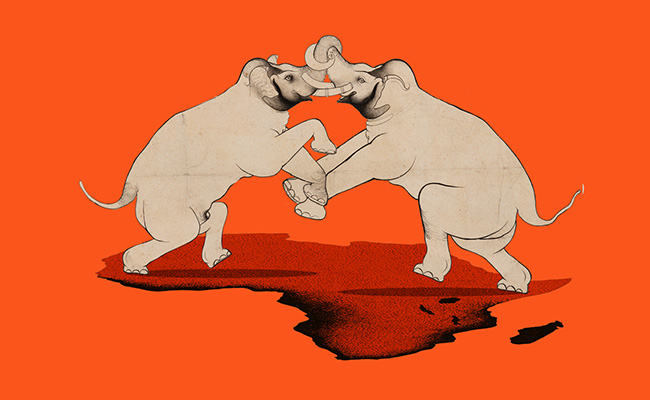

Since its launch in June, after the ANC lost its majority in national elections, early optimism has given way to friction with its main partner, the DA, over policy battles ranging from National Health Insurance to empowerment rules and land reform.

The rift widened in February when the National Treasury kept the 2025/26 budget secret from the governing coalition. The fallout – sparked by a proposed VAT hike – saw opposition parties withdraw support, delaying approval until June. The third version was passed only in June after winning support for deferring the VAT increase until 2026 and promises of tighter control over state spending.

This mini-budget will show whether those fragile compromises can hold amid slowing growth, high debt and political cage-rattling before next year’s local government elections.

1. The politics of the GNU

“Politicking around the budget creates too much harm and should be avoided,” says Japie Kok, political analyst at the Network of Risk Analysts. “The GNU would most likely want to show unity from their different leaders.”

Ramaphosa recently convened GNU leaders for a weekend retreat at the Cradle of Humankind in a bid to reset relations. ANC spokesperson Mahlengi Bhengu tells Currency that the GNU must also “ensure energy security, infrastructure recovery, and anti-corruption as foundations for confidence and sustainable growth”.

The budget “reflects ANC priorities: a capable, developmental state that works with business and labour to expand jobs, industrialisation and transformation”, Bhengu adds. “We support controlled reforms in logistics, energy and public service efficiency, but reject austerity that harms the poor.”

Citadel chief economist Maarten Ackerman doubts the calm will last, given that the GNU is still wobbly and that nothing has really changed in terms of the country’s economic fundamentals.

Besides, the ANC has a habit of springing surprises in December; think of Des van Rooyen’s four-day stint as finance minister in 2015 or the Phala Phala cash scandal that nearly unseated Ramaphosa in December 2022. The party’s five-yearly national elective conferences also typically spur uncertainty, and take place in the last month of the year, with the next one scheduled for 2027.

2. A modest revenue windfall

Treasury finally has some breathing room. Nedbank expects a R60bn revenue overshoot this year and about R200bn over the next three, supported by firm commodity prices.

Standard Bank’s Elna Moolman is more conservative: “A simple extrapolation implies upside of up to R40bn, but it’s prudent to pencil in around R20bn.” She sees the deficit narrowing to 4.4% of GDP from Treasury’s 4.8% forecast, while warning that the wage bill and interest costs could erode gains.

3. Debt peaking below 80% of GDP

After years of drift, South Africa may be nearing a debt plateau. Bastian Teichgreeber, chief investment officer at Prescient Investment Management, expects debt to peak “below 80% of GDP”, helped by slower spending and a commodity-fuelled tax boost. The Treasury in June said it expects the GDP ratio to be about 77% for 2025/26, with the debt burden peaking near 78% by 2027/28 before stabilising.

“We’ve spent less, revenue’s been higher and terms of trade have improved,” he says.

Tertia Jacobs, treasury economist and fixed-income strategist at Investec Corporate & Institutional Banking, warns the improvement is “cyclical rather than structural”, and that “without faster growth and sustained reform, the debt ratio will stabilise high and stay there”.

4. Will Treasury cut bond issuance?

Investors are watching to see whether the Treasury will trim weekly bond-auction sizes to reflect its stronger fiscal position.

“If Treasury can announce smaller issuance sizes, that would obviously be a real boost,” says Teichgreeber. A smaller supply could lift prices and push yields lower, though many analysts believe most of the good news is already reflected in prices.

5. Inflation targeting and credibility

Expect questions about whether the GNU will formally back the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) move towards a 3% inflation target.

Teichgreeber supports the shift but sees “no urgency”, as the SARB is already steering inflation towards that level within its 3%-6% band.

According to the Sunday Times, Godongwana is likely to endorse a narrower 2%-4% band – despite scolding the SARB in August for “prematurely” signalling its preference.

6. Market sentiment: cautious optimism

South African assets have quietly become one of the brighter emerging-market stories.

Anchor Capital calls 2025 “a turning-point year”, citing lower global rates, a softer dollar and record-high gold prices – bullion touched $3,500 an ounce in April – acting as tailwinds for the rand and bonds.

It expects local bonds to return about 9% over the next year and the rand, now near R17.30/$, to edge stronger towards R17. But it warns: “Without credible expenditure cuts, a meaningful decline in yields appears unlikely.”

7. The reform question

Even with a better deficit, growth reforms remain slow.

“We still have a very low pace of structural reforms,” says Teichgreeber. “You really want to grow out of your debt issues.”

Until energy, logistics and water projects move faster, South Africa risks being fiscally stable but economically stagnant.

8. Infrastructure spending: from promise to progress

Fiscal credibility means little without visible delivery.

Moolman says Treasury could use part of the windfall to “increase infrastructure spending and avoid a tax increase planned for 2026 – but only if it doesn’t derail the debt peak”.

That implies a sharper focus on ports, power and water, and tangible progress on blended-finance projects that attract private capital rather than expand state guarantees.

9. Ratings agencies are watching

The fiscal improvement “opens the door for a ratings upgrade”, says Teichgreeber – if debt stabilises below 80% and the primary surplus holds.

South Africa lost investment-grade status from S&P and Fitch in April 2017 and from Moody’s in March 2020. Even a shift to a positive outlook from one agency would buoy sentiment and reduce borrowing costs, though agencies will want proof the GNU can maintain cohesion through 2026.

10. How should you position your portfolio?

Not everyone is rushing into risk. Citadel’s Ackerman says portfolios remain defensive: South African bonds are offering yields of about 9% on the 10-year, but that’s too little for the risk.

Citadel has cut its bond exposure in South Africa and the US in phases, parked more in cash – where yields are similar but safer – and leaned into hedge funds, with a bias for market-neutral strategies.

Commodity counters have been the year’s clear winners on the JSE, buoyed by gold and platinum, while SA Inc shares tied to the local economy continue to lag.

Kok of the Network of Risk Analysts says there are still risks. The ANC could be pushed into a corner over its cadre-deployment strategy and transformation agenda. “A rethink of transformation may be on the cards, and the professionalisation of the civil service –including making it smaller – may satisfy the DA,” he says. But if the DA pushes too hard, “it could force the ANC into a corner politically”, risking a breakdown in co-operation.

As Standard Bank’s Moolman notes, the story now is less about one deficit number than about trust – trust in the Treasury’s restraint, in the coalition’s unity and in South Africa’s ability to finally shift the economy into a higher gear. This mini-budget will show whether the GNU can steer the country towards stability – or leave it idling in neutral.

Top image: Finance minister Enoch Godongwana. Picture: Gallo Images/Jeffrey Abrahams; goldprice.org; Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.