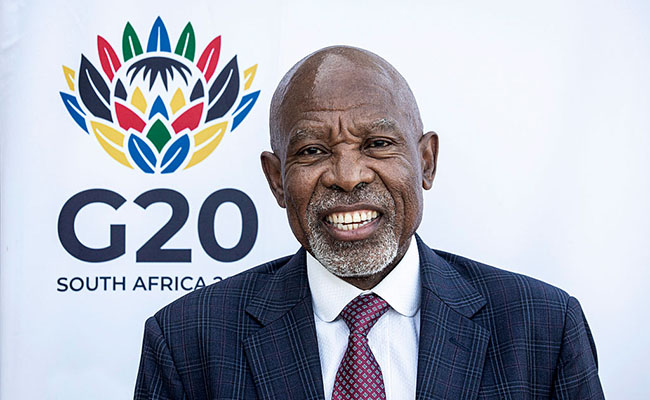

South Africans are heading into another year of interest-rate relief. Still, the path will again be uneven as South African Reserve Bank (SARB) governor Lesetja Kganyago and his monetary policy committee (MPC) steer inflation towards the new 3% target endorsed by the finance minister.

The SARB delivered a unanimous 25 basis point reduction in the repo rate on Thursday, lowering the benchmark to 6.75% – its lowest level in three years. Policymakers also trimmed their inflation outlook for 2025 and 2026, noting that a recent uptick in the pace of price increases is seen as temporary.

“We have seen four cuts this year, and those have been a sort of stop-and-go,” says Michał Jóźwiak, market analyst at global financial services firm Ebury, referring to the two pauses, one in April and another in September. “I would expect this to continue – the next meeting a pause, then another cut.”

After repeatedly undershooting its forecasts, the SARB is counting on the rand’s appreciation and lower oil prices to keep inflation in check, with headline inflation seen averaging 3.5% in 2026, down from an earlier estimate of 3.6%, and slowing to 3.1% in 2027. While inflation has accelerated somewhat over the past few months, reaching 3.6% for October, from 3.4% the prior month, the uptick is mainly due to meat, vegetables and fuel, and is likely to be temporary, Kganyago said.

“Members [of the MPC] agreed there was scope now to make the policy stance less restrictive, in the context of an improved inflation outlook,” he added.

And while the SARB has leeway to be one percentage point either side of the target, Kganyago emphasised that the tolerance band is not a range. “We want to be at 3%,” he said. But he also noted that no central bank can always hold inflation at a single level, and that flexible inflation targeting requires a measured response to shocks.

“When there are deviations, we will explain what has driven inflation away from target, and we will do what is required to get back to target,” the governor added.

A 12- to 18-month lag

Much of the confidence behind the cut rests on core inflation, the primary measure watched by the SARB as it strips out volatile items. It has held below 3.2% over the past eight months. This, Jóźwiak says “fully validates rates to be cut further at upcoming meetings, if the outlook doesn’t change drastically”.

He believes South Africa’s terminal rate – the rate at which the repo might settle during the current easing cycle – could fall to 5%, reflecting what he describes as a typical emerging-market position of roughly two percentage points above the inflation target. However, Jóźwiak stresses, this is an estimate rather than a precise prediction. Rates have been cut by a cumulative 150 basis points since September 2024.

For households, the full advantage of lower rates still lies ahead. Standard Bank head of South African macroeconomic research Elna Moolman says that while the relief for borrowers is immediate, “the total impact on the economy tends to peak only about 12 to 18 months later”.

“The maximum impact on consumer spending of the interest rate cuts in this cycle will be next year,” she says, adding that by then, rising share prices should also help spending – just as the fading benefit of low inflation would otherwise have started to pinch households.

Moolman also warns that it cannot be taken for granted that rate cuts will happen “at consecutive meetings”.

The SARB would want to assess how inflation expectations evolve under the new target. That aligns closely with the MPC’s messaging. It said its decisions will remain “meeting by meeting” and will be guided by “careful attention to the outlook, data outcomes, and the balance of risks”.

‘Better, but not yet healthy’

Finance minister Enoch Godongwana underscored the shift in his mid-term budget speech, stressing repeatedly that the 3% target was his decision – the first adjustment to South Africa’s inflation goal in 25 years. Kganyago first signalled the shift at the end-July MPC meeting, when he said the SARB “prefers” to aim for the bottom of the old 3%-6% range – effectively placing 3% at the centre of its policy framework months before the formal target change.

Kganyago said second-quarter GDP growth of 0.8%, compared with 0.1% in the first three months of the year, had surprised on the upside. Early indicators for the third quarter were “broadly positive”, prompting the SARB to raise its 2025 GDP forecast from 1.2% to 1.3%, with growth “nearing 2%” in 2027.

While employment is rising, household spending remains resilient and two-pot withdrawals continue to bolster disposable income, business investment has disappointed, shrinking in the first half of the year. A recovery in the second half is needed before the SARB can be confident that the economy is returning to its historic growth trend.

“As it stands, growth is better, but not yet healthy,” Kganyago said.

The MPC’s own risk analysis shows why the road to lower rates probably won’t be a straight one. One scenario imagines a US-dollar rebound strong enough to push the rand back to its 2023 levels, unwinding some of its almost 10% gain against the greenback this year. The second scenario builds in sharply higher administered prices linked to Eskom’s R54bn tariff error, which may result in inflation expectations “staying higher for longer”.

In both cases, Kganyago said rates would “come down more slowly compared to the baseline”.

Top image: Lesetja Kganyago. Picture: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.