“There is no safe level of exposure”, says Robyn Hugo, director of climate change engagement at environmental activist organisation Just Share, speaking of industrial emissions. “These pollutants have extremely dire impacts on human health.”

And yet, parts of Mpumalanga and most recently Gauteng are widely exposed to these hazardous emissions, being engulfed in rotten-egg-smelling air that is rich with hydrogen sulphide.

Around this time every year, Joburgers complain of this smell in the air. Yet each year, the petrochemical giant seemingly at the centre of the issue fails to confront head-on the question of the source.

So, when the foul-smelling cloud descended over the city again last week, Sasol stated that its Secunda operations are “stable” and operating “well within the limits authorised in our atmospheric emissions licence”.

It’s hardly a denial that the emissions emanated from its plant.

Environmental activists say the pollution definitely comes from Sasol, it is definitely toxic, and the reason Sasol gets away with it is that South Africa’s air pollution laws allow it to.

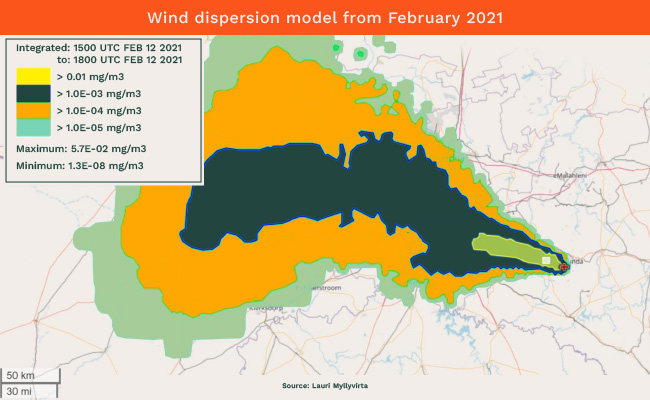

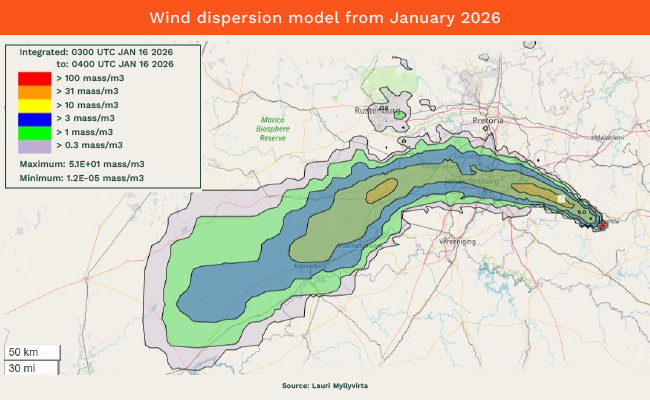

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air has noted for several years the repeated dispersion of toxic hydrogen sulphide from the Secunda area moving east to Joburg.

“The reason this happens in the summer is the wind directions – easterly winds are much more common,” he says.

Hugo adds: “It’s not just that Sasol is the only plausible source, but [Myllyvirta’s model] actually predicts that this air mass from Secunda to Joburg arrives when people are reporting the odour.”

Sasol’s response – that things are business as usual – seems to be precisely the problem.

“The process of running the plant is so incredibly dirty, and the country’s environmental regulator is so lenient, that permitted routine emission can cause severe pollution more than 100km away depending on wind conditions”, says Myllyvirta.

Sasol did not reply to questions from Currency as to whether the smell over the city could have come from Secunda, despite it “functioning within normal parameters”.

‘Rampant non-compliance’

Minimum emission standards (MES) for industrial activities were introduced in 2010, and companies have had more than 15 years to meet compliance for this bare minimum law.

“Ultimately, various industries have still never complied,” says Hugo.

Major polluters like Sasol and Eskom have argued for exemptions and launched litigation for years to try and stay the process of lowering emissions. Sasol initially sought to be entirely exempt from the MES in 2014 – something that, Just Share argues, is simply not allowed in law. Instead, it was later granted a postponement.

It subsequently applied for an “alternative” (weaker) emissions limit for its Secunda plant – an application the National Air Quality Officer turned down.

However, in 2024, Barbara Creecy, then the minister for forestry, fisheries and the environment, granted Sasol’s appeal for this “alternative” limit on its sulphur dioxide emissions at Secunda to be permitted until 2030. Sasol, Just Share argues, has sought leniency beyond this deadline.

Just Share has vociferously opposed the appeal granted by the minister. “It has always been made very clear that exemptions from minimum standards are simply not legally permissible,” it says.

The organisation notes that the country’s National Air Quality Officer in 2023 said Sasol had already been granted the single postponement to which it was entitled, and that any deviation from the MES – including by alternative emissions limits – would be contrary to legislation.

It all points to “rampant non-compliance with air quality legislation”, in Hugo’s view.

Meanwhile, Sasol has said it aims to reduce its emissions by 30% by 2030, but only an 8% reduction had been reached by 2024, and the currently exempt Secunda boilers will still be running after 2030 in any case.

The limit … does not exist?

South Africa’s emission standards, already not complied with, are some of the weakest in the world.

The stats speak for themselves – South Africa’s MES are weaker even than those in other developing countries. Our sulphur dioxide MES is more than 38 times weaker than the standard enforced for the vast majority of China’s existing coal fleet. And when it comes to hydrogen sulphide, the gas that causes that lingering smell, the limits are almost non-existent.

Dangerously, hydrogen sulphide can combine with other pollutants to create the most hazardous of all air pollutants, the innocuously named “particulate matter 2.5” (PM2.5). Its particles are just small enough to penetrate the lungs and enter the bloodstream.

A 2025 report produced by Greenpeace Africa found that South Africans were breathing air with 27 micrograms per cubic metre of PM2.5 on average. The World Health Organisation’s guideline for PM2.5 is five micrograms per cubic metre.

The department of forestry, fisheries and the environment noted the seriousness of this health hazard to South Africans back in 2022, when the department resolved to introduce an ambient air quality standard for hydrogen sulphide. Most other harmful pollutants like sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide are already limited by these ambient air quality standards.

The department also set up a task team in 2022 to provide recommendations on interventions to improve the effects of hydrogen sulphide.

But as of 2026, there is still no ambient air quality standard to control hydrogen sulphide in the air, despite the kilotons of it produced by Secunda, the “major source” of hydrogen sulphide in South Africa.

The department tells Currency that the task team’s recommendations are “currently under implementation” and that it is “undertaking a review” of the ambient air quality standards as part of these recommendations. Naturally, there was no explanation as to why it is taking so excruciatingly long.

Until such time as these reviews turn into actions, South Africans can expect to only be choking on more fumes.

This story has been updated to reflect new statistics for South Africa’s MES.

ALSO READ:

- How Sasol went rogue on its climate ‘plans’

- Why is coal miner Glencore doing a ‘green energy’ deal with Discovery?

- Why Sasol still calls the climate shots

Top image: Pexels/Sherissa/Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.