“Malta is the golden clasp that ties the history of the sea together.” – Samuel Griswold Goodrich

Of all of Leon Louw’s extraordinary interactions with economists and politicians around the world, one in particular bears expansion because its effects were profound, and because it ended up almost creating a free market experiment on an island in the Mediterranean. That’s not something that happens every day. That island was part of the Maltese archipelago.

The story centres on a South African businessman by the name of John Sherry who started a listed electronics firm in South Africa called Jasco in 1976. Sherry was born in Malta, but studied and worked in the UK before moving to South Africa. He led the company as board chairman until 1998 and remained a non-executive director until his retirement in 2016. He died in 2019.

On his retirement, he went back to Malta, became involved in humanitarian work, and was eventually honoured as a Knight Chevalier by the Maltese government. But even before then, he was deeply involved in the politics of Malta. The islands – there are eight of them, with Malta by far the largest – have been a crucible of international politics for centuries, partly because of their strategic position slap-bang in the middle of the Mediterranean. Malta was fought over during the Punic wars between Rome and Carthage in the centuries before the death of Christ. It was besieged in 870AD by the Aghlabids, an Arab Muslim dynasty from North Africa. The Great Siege of Malta took place in 1565 when the Knights Hospitaller repelled the Ottoman expansion.

Malta was a feature in the Napoleonic Wars, and was successfully invaded by the French under Napoleon Bonaparte. Despite holding on to the territory for only two years, Napoleon introduced lasting administrative changes, notably stripping the royalty of their legal privileges. Napoleon’s invasion prompted the intervention of the British, and despite the 1802 Treaty of Amiens requiring Britain to return Malta to the Knights Hospitaller, Britain opted to retain control due to its strategic importance. It was formalised as a Crown Colony in 1814 and served as a key naval base, supporting British operations in the Mediterranean during both World Wars.

Consequently, when Malta gained independence in 1964, its economy remained rooted primarily in its historic function, as a military base. It was heavily dependent on the British military presence, with the naval base and related activities constituting about 20% of GDP. The economy was underdeveloped, with limited industrialisation, high unemployment, and reliance on agriculture, fishing and colonial subsidies.

The first government was nationalist in character, promoting tourism and light manufacturing, but progress was slow, and the economy remained vulnerable. A fiercely socialist victory at the polls by the Labour Party followed in 1971, and key sectors, including the banks, telecommunications, and parts of the energy sector, were nationalised. The government joined the Non-aligned Movement, tried to reduce reliance on Western powers, and aligned itself particularly with Libya.

It all seems so familiar. Economically, the result was not disastrous, but growth was sluggish. Social improvements were registered, but the economy became progressively more fragile and the Labour Party was transparently losing support. The key figures here were the two Labour Party presidents, Dom Mintoff (1971-1984) and Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici (1984-1987). During his presidency, Bonnici accelerated the socialist economic experiment, but inevitably, that just made things worse. At this point, Sherry, a very respected figure on the island, suggested they talk to his old mate from South Africa, Leon Louw.

Louw was asked to present a range of proposals to the government. “I came up with a blueprint of economic policy, which, amazingly, was implemented.”

Louw says the policies had to look like socialism, but were actually aimed at free market reforms. Louw’s proposals were wide-ranging; it helped that they were the kinds of reforms supported later by the European Union, other key people in the business sector, and various advisers.

One of Louw’s innovative ideas was to propose that many changes could be purely administrative. For example, the government could technically keep control of issuing taxi licences; all it had to do was issue an administrative order that everyone who applied for a taxi licence would get it immediately. He made similar proposals regarding other red tape constraints across the administration, like the tight building codes.

The most far-reaching change was his proposal to encourage the establishment of Malta as an entrepôt (transshipment) port. This kind of port is a trading hub where goods are imported, stored, then re-exported without undergoing significant processing or manufacturing changes. The key diffence with Malta’s law at the time was the necessity to have low or no customs duties on goods meant for re-export, making it attractive for international trade. It’s important that the port does not require major manufacturing, but there is often processing, such as repackaging, labelling and quality checks before re-export. The change leveraged Malta’s position as a trade route for ships coming through the Suez Canal from Asia, and its historic ports built during its involvement in successive conflicts.

The other thing Louw suggested was reducing red tape in the tourism industry by specifically allowing Maltese citizens to run bed-and-breakfast establishments, for example. Once again, this was leveraging Malta’s pre-existing natural competitive advantage, being an English-speaking island in the sunnier and warmer part of the Mediterranean. There were many others.

Economic growth started to pick up aggressively, and the Labour government presented Louw with an award in recognition of his contribution. It was during this period that he tried to convince the government to use one of the islands as a libertarian haven where they could establish the ultimate free economy, with free banking, free currency, free everything.

The island they had in mind was Fila, which is a mostly barren and uninhabited islet 4.5km south of Malta, the most southerly point of the Maltese archipelago. The only problem was the island’s size, covering only about 10 hectares, and its huge cliffs on all sides; it looks like a fortress rising dramatically out of the sea.

“There is very little surface area you could develop, and we decided that it wasn’t feasible,” Louw says. “But now I think that was a mistake. If I’d had the time and energy, it would have been worth just doing it and seeing what would happen.”

As it turned out, the Labour Party lost the next election, despite the improving economy. Louw says that when he visited members of the new Nationalist Party government, they said to him, “Thanks for the policies, we just carried on implementing them.”

Malta’s growth rate continued at pace, and the new government initiated a campaign to join the EU, which required a whole new set of free trade reforms. Malta joined in 2004 and adopted the euro in 2008, integrating into the Eurozone’s economic framework.

This facilitated access to the EU’s single market, boosting trade and investment. Capital controls were fully lifted upon accession, shifting Malta towards a market-driven economy.

After this, growth really took off, with GDP increasing on average 6.5% annually between 2014 and 2023, one of the highest rates in Europe. Maltese income per capita is now slightly higher than the EU average and unemployment is extremely low. But there have been several high-profile scandals in Malta in the 2010s and 2020s, loosely associated with the Labour Party, which regained power in 2013.

Economically, the changes wrought during its economic crisis period have largely stuck. For example, taxes are not low, but they are lower than in many other countries in Europe. They are not as low as they might have been on the island of Fila (zero!) if the experiment of a totally economically free state had been implemented.

Pity!

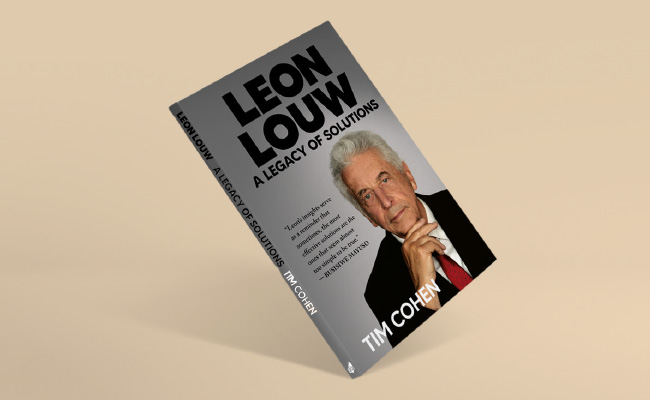

‘Leon Louw: A Legacy of Solutions’ by Tim Cohen is published by Maverick 451 and is available at a recommended retail price of R360.

ALSO READ:

- How Capitec’s ‘seven dwarfs’ built a banking behemoth

- The One Thing …

- Behind the birth of cadre deployment

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.