The global shift towards private markets is no longer a niche phenomenon confined to Silicon Valley venture capitalists or buyout funds. It is becoming a defining feature of modern capital allocation – and, increasingly, a response to the growing complexity and compliance burden of public markets.

This is the view articulated by Westbrooke Alternative Asset Management head of investor solutions and director Dino Zuccollo in an interview with Currency. Zuccollo argues that the traditional logic of listing has been fundamentally inverted.

“In the past, listing was the endgame,” Zuccollo says. “It was the big liquidity event – the point at which founders monetised what they had built. Today, being listed is increasingly seen as an impediment to growth.”

Historically, listed companies traded at a premium. Public markets offered access to deep pools of capital, liquidity and valuation uplift. But Zuccollo argues that this premium has quietly become a penalty.

“Being listed brings regulation, red tape, disclosure requirements, quarterly pressure – and, in a world where speed matters, that can slow you down,” he says. “The ability to move quickly is often the difference between success and failure.”

This is particularly evident in technology and platform-driven businesses, where first-mover advantage can determine the entire outcome. “There’s only one Facebook. There’s only one Uber. The rest fall by the wayside.”

From premium to penalty

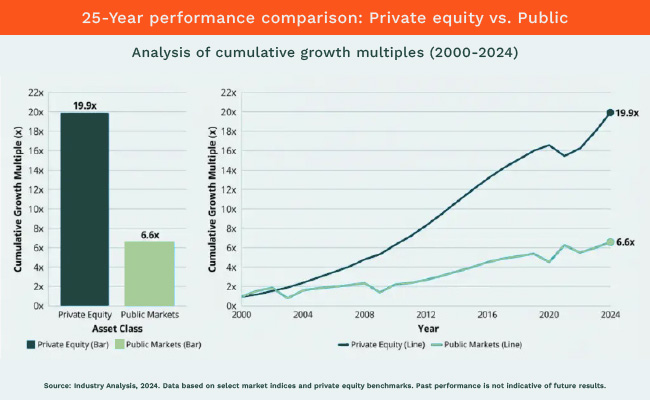

The data backs this up. The average age of a company at IPO has risen from eight years in 2004 to about 14 years in 2024, meaning much of the highest-growth phase now happens while companies are still private.

“That early growth period is where the value is created – for founders and early investors,” says Zuccollo. “By the time companies used to list, a lot of that upside was already gone.”

Crucially, companies no longer need public markets to raise large amounts of capital. Private capital has scaled to institutional proportions.

“Thirty years ago, if you wanted serious capital, you had to go public,” Zuccollo says. “That’s no longer true.”

So how exactly does this private “members’ club” function?

Private markets, essentially, are investments in companies, assets or loans that are not traded on public exchanges, where capital is committed directly or through specialised funds. This is done typically in return for longer holding periods, less liquidity and greater exposure to underlying business fundamentals than in listed markets. They include private debt, private equity, hybrid capital, real estate and some venture capital.

Global private market managers now deploy capital on a scale once associated only with stock exchanges and banks. Firms such as Blackstone, Apollo and others rival national economies in terms of assets under management and revenue.

“The pool of available private capital is vastly larger than it used to be,” says Zuccollo. It means entrepreneurs can fund growth without surrendering control or absorbing the compliance costs of a listing.

Leaving a gap

This shift has been accelerated by the retreat of banks from certain types of lending, creating space for private credit and hybrid capital to flourish – a trend that has little to do with technology hype and everything to do with structural changes in finance.

The move towards private markets is not only about companies staying private. It is also being driven by investors grappling with concentration and correlation risks in listed markets.

In the US, the “Magnificent Seven” now account for roughly 55% of the S&P 500’s performance, meaning portfolios that appear diversified are, in practice, highly concentrated.

“At the same time, bonds and equities are now moving in the same direction,” says Zuccollo. “The old 60:40 portfolio no longer works as a shock absorber.”

Private markets, he argues, are increasingly filling that role.

“When you have assets that are genuinely uncorrelated – priced on fundamentals rather than headlines – they can stabilise portfolios in ways traditional assets no longer do.”

Globally, the allocation gap is stark. In the US, high-net-worth investors have shifted from roughly 3% exposure to private markets to more than 20%, with some family offices closer to 50%. By contrast, South African investors remain far behind.

The problem with very small allocations is that private investments “don’t move the needle”.

He says: “If you’re allocating 3% of a portfolio, even spectacular performance won’t materially change outcomes.”

At allocations closer to 20%-25%, however, private assets can provide meaningful diversification while liquidity is maintained elsewhere.

A common misconception is that private markets are synonymous with illiquidity. Zuccollo says the reality is more nuanced.

“Many private market products now offer quarterly liquidity, others six to 12 months, while private equity remains locked in for longer,” he says.

But he cautions against forcing private assets into daily pricing structures. “The benefit of private markets is precisely that they’re not repriced every time a politician says something or markets wobble.”

Offshore allure

“High-net-worth South Africans typically have over 80% of their assets offshore, and private market exposure is following that trend,” says Zuccollo.

Locally, the ecosystem has historically been thin outside hedge funds and private equity. But private debt, in particular, is growing as non-bank lenders step into gaps left by traditional banks.

“South Africa has been slow, but sentiment is changing,” he says. “Load-shedding has eased, inflation is lower and political stability has improved. Optimism is returning – and that’s where capital flows start.”

Whether that sentiment translates into sustained domestic investment remains to be seen. But the structural forces driving private markets – regulatory pressure on public companies, abundant private capital and portfolio diversification needs – show little sign of reversing.

As Zuccollo puts it: “Private markets aren’t replacing public markets. They’re filling the space public markets have made too expensive to occupy.”

This story was produced in partnership with Stanlib.

ALSO READ:

- Private equity’s ascension need not hurt public markets

- Hard concentration: The real problem with Big Tech’s dominance

- Are today’s ‘safest’ equity bets tomorrow’s risks?

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.