The last time we human beings ventured into space beyond low-earth orbit was in 1972; it was the year of the last of the Apollo missions and the last time we set foot on the moon. It was also the year that the pioneering artist Alma Thomas became the first black woman to hold a solo exhibition at the a major American museum, the Whitney. As it happens, in the next few weeks NASA aims to put humans back in the orbit of the moon, and I think we could learn a thing or two from the fervent canvasses of Alma Thomas, who surrendered wholeheartedly to space-race fever.

In early February, NASA hopes to launch the second of its planned Artemis missions, which are named for mythological Apollo’s twin sister. Artemis II is only a recon mission, with plans for an actual moon landing (Artemis III) scheduled for around 2028.

This will be the first time in over half a century that humans will be back in deep space. Which also makes it the first time in my lifetime, and the lifetime of any other millennial, and all those who have come after. I feel we’re all being very blasé about this imminent and astonishing event. So, I’m rolling out a little reminder of how to be awestruck, courtesy of Alma Thomas.

Learning how to be awestruck again

Alma Thomas, the first black woman to be granted a degree in fine arts from an American university (in 1924), was a trailblazer herself. She’s best known for her later abstract works, which are defined by mosaicked brushstrokes of colour hovering on pulsing colour fields, creating shimmying sensual evocations of the world around her.

Nature and music were her two big inspirations; her art is led by colour and rhythm. Her titles reflect the vibrant, multisensory world she inhabited: Old Pond, Red Sunset Concerto; White Roses Sing and Sing; Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers.

She was 80 when she held her groundbreaking solo exhibition at the Whitney. In the preceding three years NASA had sent six crews of astronauts to the moon, and more unmanned probes into deep space. The otherworldly images and accounts being sent back to Earth lit a fire under Thomas, who produced a prolific series of space paintings including Starry Night and the Astronauts, Mars Dust, Blast Off and more.

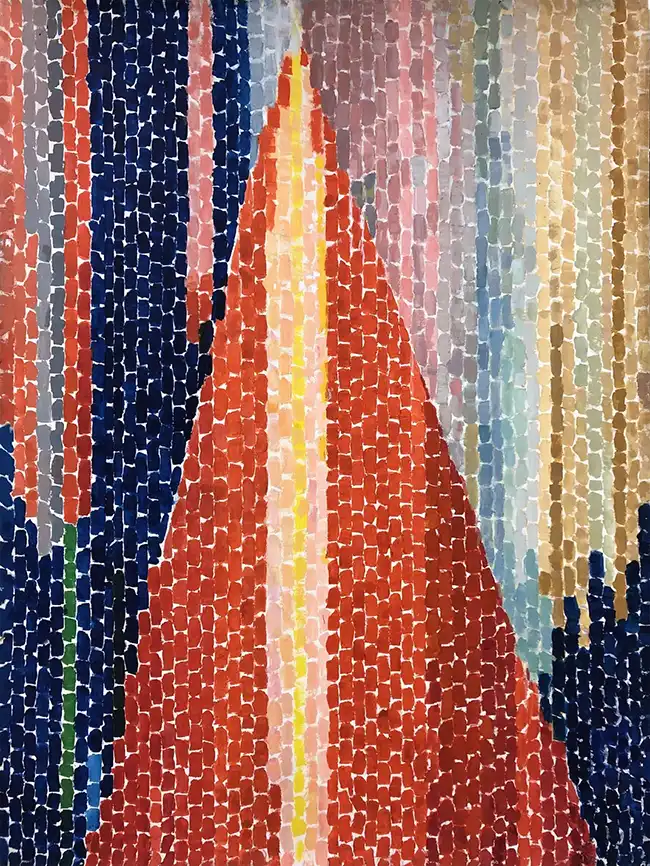

In Blast Off, you can almost feel the reverberations in front of an enormous fiery peak of reds, oranges and white-hot yellows, crowned by an almost-invisible rocket, a single tiny brush stroke of grey. And what’s that in the background, whizzing past dizzyingly? Earth, in all its blurred randomness, its deep blues and gentle pastels? Or is it space itself and the indeterminate future hurtling towards us?

As with many abstract works, you have to see these canvases in person to experience the physical effect of colour and form on the human eyeball, to appreciate the way they tremble with excitement and velocity.

When the moon came into the living room

The explosion of colour TV in the late 1960s meant that interstellar images and broadcasts were coming directly from the Apollo missions into living rooms, in full colour. This itself was something extraordinary: a marvel, a wonder!

It was also something Thomas acknowledged and celebrated in her artist statement: “Today not only can our great scientists send astronauts to and from the moon to photograph its surface and bring back samples of rocks and other materials, but through the medium of colour television all can actually see and experience the thrill of these adventures. These phenomena set my creativity in motion.”

Thomas knew that the world needs storytellers as much as it needs scientists. That colour TV broadcasts were as much something to celebrate as landing on the moon. From a distance, you might ask, was this some halcyon age when technology was pure and noble? While we sit wringing our hands, with AI hanging over heads like the sword of Damocles? No, technology is always double-edged – Alma Thomas just knew what deserved a good cheer.

Snoopy goes to space

In 1967, before Apollo 11 became the first crewed craft to land on the moon, Apollo 10 was sent to “snoop” out the moon landing (just as Artemis II will do this year). The lunar module was endearingly nicknamed Snoopy.

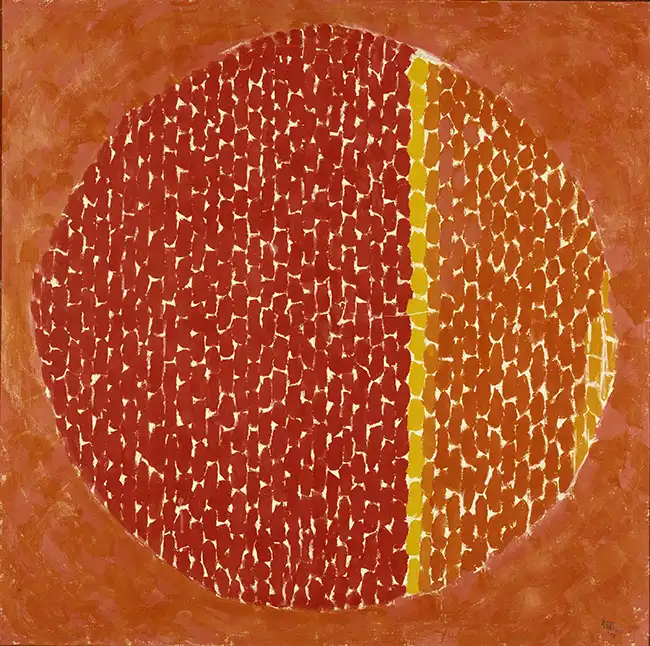

Thomas produced a whole series of canvases based on what Snoopy saw: Snoopy Gets a Glance at Mars and Snoopy Sees a Day Break on Earth, for example. Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset is a canvas painted a gentle orange, with a softly vibrating orb in the centre made up of her signature coloured strokes. Half the sphere vibrates in vertical red lines, until abruptly, there’s a glowing yellow stripe and then a transition into oranges. Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset is the embodiment of warm and fuzzy. There’s a mesmerising absence of cynicism in these paintings.

What we lost in the process

In 2026 some of us are still retching from seeing Katy Perry in a designer space suit during the last rocket-fuelled billionaire’s publicity stunt, so forgive us our cynicism. The promotional videos on NASA make no bones about the Artemis missions being the first step towards a permanent settlement of the moon (the goal of Artemis III is to drill for water-ice) and ultimately towards the exploration of Mars. And it costs billions and billions of dollars to bring these missions to fruition. Now hear the chorus wailing about All the Troubles Here on Earth!

There are many arguments to be made against space exploration, but there was no way that space was never going to call to us, and there was no way in which we were never going to answer. Exploration and novelty are part of the hardware of our neurocircuitry – something that this century’s tech was quick to capitalise on; our brains are wired to chase rabbits down the black holes of social media, and they are wired to get us to the moon. In fact you could make a trip to the moon in the time it would take to list all the artists, songwriters, film-makers, and writers to whom space has beckoned.

A starry comparison

In Starry Night and the Astronauts, a nod to Vincent van Gogh’s iconic starry night, Thomas raises our eyes far above the rooftops and silhouetted trees of Van Gogh’s horizon until we are staring into the dome of the heavens, an infinite midnight blue sky. Whereas the Dutch master’s dense strokes give us a visceral pulsating atmosphere, Thomas’s similarly short strokes expand outwards and upwards, they crack open to let the raw canvas shine through, so that her sky seems lit from within with the twinkling of uncountable distant stars. And as we’re watching, something flashes in the top right corner – our astronauts re-entering the atmosphere?

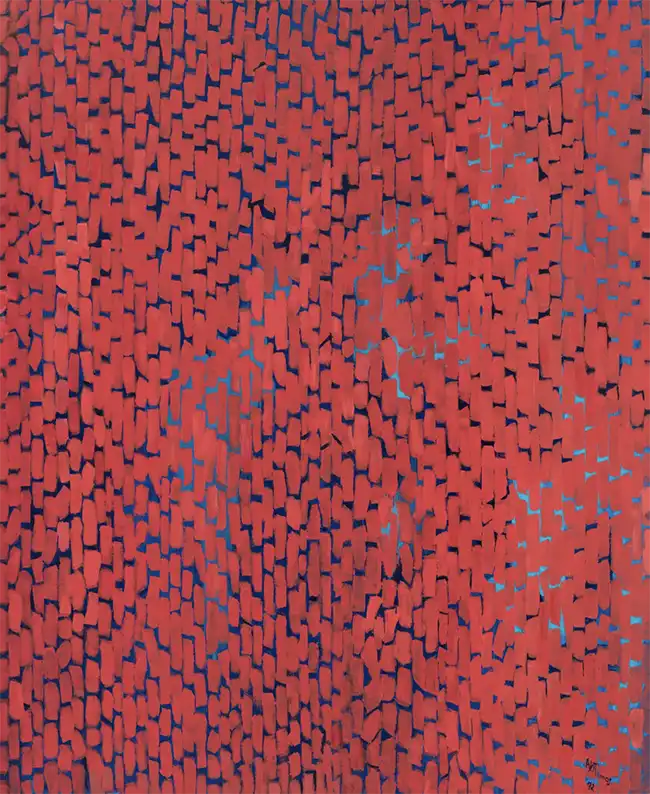

In Mars Dust, Thomas takes us into the heart of a dust storm on the red planet. Set against a shifting blue background, her red strokes fill the frame from edge to edge. The obscured background shines through, oscillating between deep blue darkness and pale cerulean flashes, but through the agitating wall of crimson we only catch glimpses. The gravitational pull of Thomas’s canvases, more than the colour optics, is really the soaring free-flight of her imagination.

The pale blue dot

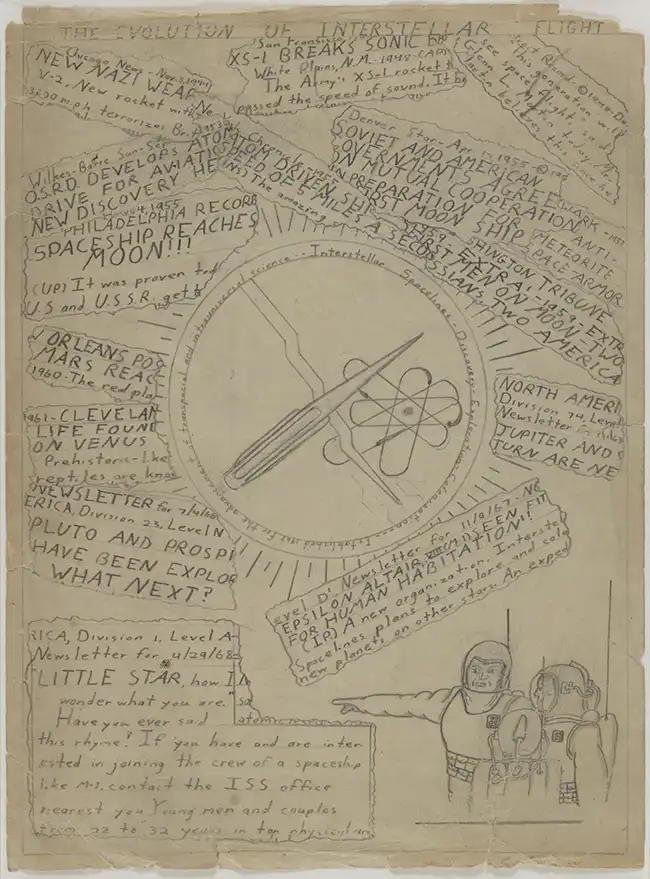

I’d also like to single out another work of art, a small drawing by the astronomer Carl Sagan. Drawn in pencil on a sheet of foolscap paper by a pre-teen Sagan sometime between 1944 and 1947, it’s a page brim-full to the margins of the best kind of imagination. The evolution of interstellar flight, as it’s titled across the top of the page, lays out the imagined future of space exploration led by the “Interstellar Spacelines” whose logo and motto take centre spot on the page.

In the bottom right corner, three astronauts in presciently drawn space suits huddle together in excited conversation, one of them gesturing expansively into the distance. The rest of the page is filled with carefully drawn fragments of what appear to be newspaper headlines. The first one from the “Chicago News” proclaims a “NEW NAZI WEAPON V2 New rocket with 3690 m.p.h.” This is the only factual headline – the first object in space was a rocket launched by the Nazis in 1944 – and the rest go on to unfold a story of reaching the moon, life on Venus, interplanetary habitation, and so on.

But the most endearing aspect of all this is the young Sagan’s emphasis on international cooperation: “SOVIET AND AMERICAN GOVERMENTS AGREE ON MUTUAL CO-OPERATION IN PREPARATION FOR FIRST MOON SHIP” proclaims one; “FIRST MEN ON MOON: TWO RUSSIANS AND TWO AMERICANS” reads another.

Sagan was a hardline scientist and a hopeless romantic. He was the person responsible for turning the Voyager spacecraft around just as it reached the edge of our solar system, to take one last photograph of the Earth. Sagan realised the importance of this perspective, Earth appears as a tiny speck, “a pale blue dot”. This photograph was the descendent of an image taken by the Apollo 8 crew of the dramatic and ethereal “Earthrise” over the moon, a photo that is credited with influencing and giving impetus to the burgeoning environmental movement of the 1970s. These are two images that fundamentally changed how we humans saw ourselves and our planet.

What space can still do for us

So, to answer the cynics and the fretting chorus: it’s true that after exploration comes exploitation, it’s true that space travel has become a billionaire’s dick-swinging contest, and yes, it’s true that there are many Earthly affairs that need our attention… Yet it is also true that space can bring out the best in us, it can make us more human, more in love with our planet, more in love with each other. Its limitlessness is the just the right size for our imagination and creativity.

Which is why, on the brink of this next journey, I’m rooting for Alma Thomas’s exuberant wonder and Carl Sagan’s idealism. We need constantly to remember what is worth paying attention to. And perhaps just what we need in our current age is some new celestial footage of our home – now live-streamed on NASA’s YouTube account – something that can, as Alma Thomas put it, “set our creativity in motion”, and expand our horizons beyond small terrestrial tyrants.

P.S. if you’d like a little boost of national pride too, the South African National Space Agency (did you even know we have a National Space Agency?!) is collaborating with NASA at the new Matjiesfontein Deep Space Ground Station, which will form part of the network of antennae in the Lunar Exploration Ground Segment set up between the USA, South Africa and Australia to make sure that the Artemis missions will have constant comms with Earth.

For more of Rebecca’s wonderful thinking, go here.

Top image: Alma Thomas

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.