South Africa’s film and television industry is sliding towards a cliff edge after the government’s film incentive adjudication committee failed to sit for more than a year, leaving thousands of applications unprocessed and hundreds of millions of rand in claims unpaid, industry leaders warn.

In an interview with Currency, Wandile Molebatsi, deputy chair of the Independent Producers Organisation (IPO), says the film and television production incentive (FTPI) – a legislated rebate system used to attract local and foreign productions – has effectively stalled since October 2023, with devastating consequences for producers, workers and South Africa’s competitiveness as a global filming destination.

“The adjudication committee has not sat since October 2023. That means thousands of submissions aren’t even being looked at,” Molebatsi says. “Without an approval letter, producers cannot raise finance. Projects simply die.”

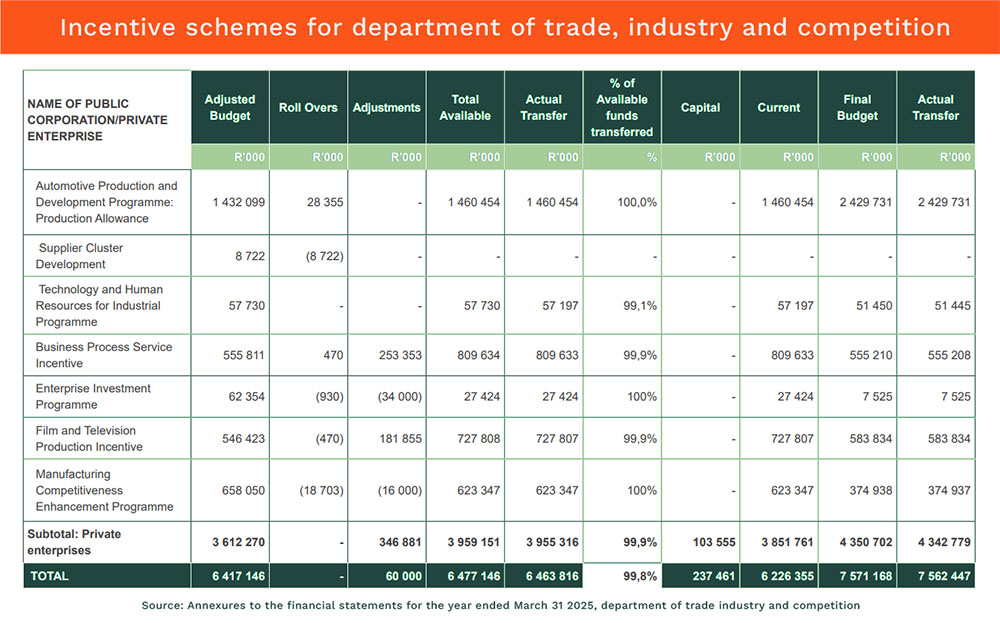

The FTPI is one of only seven incentive schemes run by the department of trade, industry and competition (DTIC), and government-produced figures suggest everything is normal.

However, the industry argues this presentation is very distorted. What happened is that in February 2024, a tense meeting took place between representatives of the film sector and the then minister, Ebrahim Patel. The industry was up in arms following lengthy delays in film incentive scheme payments to productions, totalling R663m, some dating back four years.

The ministry committed to clearing the backlog, and doing it quickly. But according to Nimrod Geva, a TV producer with nearly 20 years’ experience in the industry and a former co-chair of the IPO, in order to find enough funds to pay what was already owed, the department apparently decided to save money by not approving any new projects. The effect was to freeze the incentive scheme.

R500m a year

Industry incentives are a complex and controversial topic, but in one sense, the movie industry is different, because almost every single country that has a movie industry is supported financially by the government concerned – even Hollywood movies get tax rebates from the state of California.

The extent of these rebates is typically very small compared to the total budget of the countries concerned. The UK for example, spends roughly £1.5bn-£2.0bn a year on film and high-end TV tax relief (now called Avec). That’s about 0.12% of total UK public spending of £1.2-trillion.

South Africa’s scheme was until recently well recognised internationally and, according to producers, worked well, even though it’s a rebate scheme, not a tax deduction, which is simpler to administer.

It’s also very small – much smaller than the international average. South Africa has spent about R500m a year on the incentive scheme over the past decade, which constitutes 0.02% of the nation’s annual expenditure.

The automotive industry support scheme costs about R50bn a year, if you include the reduced excise duties that form part of the scheme. Even without the excise reduction calculation, just the production allowance granted to the car industry is almost triple what movie production gets.

Geva adds that about 80% of the rebate actually comes back to the government in payroll taxes, and taxes on purchases made in the process of producing a movie.

The economic impacts

The trump card of the movie industry is the production of a new report that suggests the incentive has been one of South Africa’s most effective industrial policy tools.

The 2025 Olsberg Report – commissioned by the IPO with support from the Industrial Development Corporation, Gauteng Film Commission and Netflix – finds that between 2015 and 2025 the FTPI generated:

- R26.4bn in gross value added (GVA);

- R13.9bn in employee compensation; and

- An average return of R5.10 in GVA for every R1 of public expenditure.

The study shows that foreign film and post-production incentives accounted for roughly 85% of qualifying spend, delivering the strongest economic returns, while domestic and co-production incentives remain underused despite their importance for local storytelling and transformation.

Crucially, Olsberg also found that 57%-64% of production expenditure flows into non-screen industries, including construction, transport, hospitality and professional services – underscoring the sector’s broader economic footprint.

Yet after a peak in 2022, production activity, employment and value added have fallen sharply, a decline the report links directly to administrative uncertainty, funding caps, delayed payments and declining reliability of the incentive system – all of which have weakened South Africa’s standing relative to rival jurisdictions.

Globally, countries from the UK and Spain to Canada, Australia and New Zealand have expanded or stabilised their film incentives precisely because production is mobile and capital moves fast. When incentives become unreliable, productions simply relocate.

‘An exportable product’

While some historic claims have recently been paid, Molebatsi says industry estimates suggest about R200m has been settled, leaving roughly R400m still outstanding.

That backlog, he says, is pushing producers into personal financial ruin. “People are losing homes. Children are being pulled out of school. Cars are being repossessed. These aren’t email addresses – these are taxpayers.”

A recurring government argument against film incentives is that production work is “temporary”. Molebatsi says that definition is now being challenged.

Recent labour gazetting recognises film freelancers as workers, acknowledging that while crews move between employers, they often work sequentially for months at a time, building long-term careers.

“In a country with mass youth unemployment, calling six months of paid work ‘temporary’ is meaningless,” he says. “Any employment is good employment.”

Film sets, he adds, have a relatively low barrier to entry, allowing semi-skilled young people to gain paid experience in technical and creative roles – something few sectors can replicate at scale.

Molebatsi also rejects the idea that film is a cultural luxury. “We are manufacturing an exportable product,” he says. “Just like mining extracts gold, we extract intellectual property – stories, music, images – and sell them globally.”

Film production, he argues, draws together musicians, painters, designers, actors, animators and technicians into a single value chain, making it one of the most integrated creative industries in the economy.

Indulgence or investment?

The crisis highlights a wider tension facing governments globally: whether film incentives are an indulgence or an investment.

Critics argue incentives distort markets, compete with spending on core services and fuel subsidy races between countries.

Supporters counter that when incentives are predictable and well administered, they function like export support – pulling foreign capital, skills and jobs into the domestic economy at relatively low fiscal cost.

The Olsberg findings strongly support the latter view – but only if the system works. “You can debate policy,” Molebatsi says. “But what you can’t do is leave a law in place and then stop administering it.”

With no approvals since October 2023 and producers threatening further protests and sit-ins (three have been held so far), the industry is now testing whether South Africa’s new political settlement can deliver something film producers say global investors demand above all else: a predictable, credible regulatory environment.

If it cannot, Molebatsi warns, productions will keep moving – and once crews, studios and trust are lost, they may not come back.

Approached for comment, the DTIC said it might make a statement on the issue in the near future.

ALSO READ:

- Can-do vibe emerges at the film market in Durban

- Talking about a revolution in Africa’s creative economy

- Trade shocks test auto industry survival plan

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.