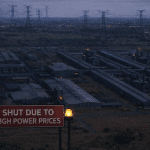

The City of Ekurhuleni, east of Joburg, is the heartbeat of Gauteng industry. Yet, strikingly, on the municipality’s website, it lists the position of group financial officer as “vacant” – which reveals so much about how dysfunctional the city really is.

Now paper and packaging company Mpact has said enough is enough. The exorbitant and erratic cost of power and water in the area are key to Mpact’s decision to close its Springs paper mill, which it announced this week.

The packaging company has now lodged court papers against Ekurhuleni, for what it calls “excessive” and “unlawful” electricity charges.

In an interview, CEO Bruce Strong says that power is costing the company at least 18% more than it should – and up to 38% in some cases.

This is a significant step, vindicating the warnings from economists and analysts that the meltdown in municipal services threatens to leave President Cyril Ramaphosa’s quest to push GDP growth up to 3% stillborn.

It is a push to suggest that Mpact’s decision to close its Springs paper mill can be laid entirely at the door of Ekurhuleni’s municipal managers, where control of finances and general functions have disintegrated since a coalition between the ANC and EFF was formed in 2023.

Economic conditions such as a stronger rand have made it worse – but the municipal meltdown hasn’t helped.

Nonetheless, says Strong, the cost of the municipality’s power supply and its failure to consistently supply it, have fatally weakened the Springs mill, which produces cartonboard and which employs 377 people.

“We’re paying over R300m in electricity costs to Ekurhuleni every year and if you just take the conservative basis that we’re being overcharged 20%, you’re talking a significant amount of money over the years.”

R200m in lost working days

Between 2020 and 2025 alone the Springs paper mill lost 179 working days thanks to power and water outages, says Mpact. That works out to 30 days a year – at a cost of R2m a day. In total, Strong says the interruptions have drained it of more than R200m.

“A paper mill is designed to run 24/7 – otherwise it can’t recover its costs. So if you’re not running all the time, you’re costing yourself a lot of money,” he says.

Like almost every other industrial firm in South Africa, Mpact had to become self-sufficient wherever possible, it says, given Eskom’s lost decade of load-shedding. It ploughed north of R130m into its own backup power over the past few years: 9.4MW of solar capacity throughout its six Ekurhuleni operations, with 6MW at the Springs mill alone.

But that is money that could have been spent in other ways, and is at the crux of the mill’s lack of competitiveness.

“You’ve diverted capital from something that you shouldn’t have to do,” says Strong. “There’s no doubt we’d be under pressure now with the rand where it is and the international market where it is, but at least you’d say: ‘I can hold out for a while.’”

Economically, the closure of the Springs mill will have wider ramifications. It is the only domestic producer of cartonboard – packaging for products like cereal – and it competes directly with imports.

But given a glut of global supply and the stronger rand, the mill’s largest customers are able to import cartonboard at prices approximately 20% below its own cost of production, Mpact says.

That led to Mpact’s largest customer notifying the company that it would no longer need its services, prompting the decision to shut the mill by March. But the company retains five other plants in the municipality and, together with the Springs mill, employs about 1,000 people in the area.

‘No alternative’

Mpact has offered to pay 84% of its electricity bill to the municipality until the dispute is settled.

“We’ve approached the municipality in the past to try and get our supply directly from Eskom, and to assist in the maintenance of that infrastructure but that hasn’t been possible – so we’ve been left with no alternative other than to bring these proceedings to try and protect the rest of our operations,” says Strong.

Asked how it arrived at its conclusion that it was being overcharged, Strong says it became obvious after comparing its Ekurhuleni plants to power costs at its Felixton operation in KwaZulu-Natal, which has similar infrastructure.

“Even allowing the municipality to recover some costs, then you still come to a number that’s 20% higher,” he says.

Mpact has also brought a review against energy regulator Nersa, which it says approved the power tariffs without due process. “They didn’t consider the correct cost-of-supply study that Ekurhuleni was meant to submit and as a consequence they gave a tariff that was not justified. And it was not transparent,” says Strong.

Municipal revolt

Mpact joins a growing list of businesses that are now suing the state for services they have been charged for but haven’t been received.

The longest-running saga has been between Astral Foods and the Lekwa municipality, over its inability to provide power and water to the company’s Standerton plant. In 2021, Astral got a court order against the government and National Treasury over the non-delivery of services.

Former Astral CEO Chris Schutte told Currency last year that South African firms are increasingly becoming uncompetitive thanks to the state’s multiple failures.

“Our production efficiencies are better – but not our costs, because we have all these added things we have to do that the government is supposed to,” he said.

Piet le Roux, the CEO of business organisation Sakeliga, which is embroiled in its own legal battle to get the state to intervene in the North West’s chaotic Ditsobotla municipality, warns that there may be a lot more business casualties on the horizon.

“We’re in for a rough ride and I think people who say South Africa has turned a corner are missing key warning signs,” he tells Currency.

“I think South Africa is seeing maybe the largest wealth transfer story in the world that no-one’s heard of. These municipal electricity bills are a money-making scheme; they use that money from those willing to pay and transfer that to either corruption and self enrichment [schemes] or to buying voters.”

Le Roux uses the example of financing social housing projects funded with money earmarked for other services, like power, to shore up the ANC’s waning support.

In Ekurhuleni’s case, the municipality owed Eskom R5.8bn as of June 2025.

“It has reached such a magnitude that I think it is choking the economy,” says Le Roux.

Currency has approached Ekurhuleni for a response; its comments will be added once we receive them.

ALSO READ:

- Can Sakeliga force Ramaphosa to – finally – act?

- North West: The root of the rot

- Lights out for Joburg: Dada Morero’s big Eskom gamble

Top image: Mpact’s mill in Springs. Picture: supplied.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.