The newest president of the African Development Bank hails from one of the poorer economies on the continent – Mauritania, where GDP per capita sits at about $2,120. But it is 61-year-old Sidi Ould Tah’s ties with influential Arab states that may have swung the vote in his favour.

The Mauritanian candidate beat off four other candidates – including former Transnet group treasurer, South Africa’s Swazi Tshabalala – for the highest post at the African Development Bank (AfDB) on May 29.

It was an indication of how effectively Mauritanian diplomacy managed to mobilise a majority around its candidate among the 54 African member states and the 27 non-African members with voting rights on the Bank’s board of governors. What helped, according to the Dakar-based Financial Afrik, was the strong support Tah received from Côte d’Ivoire’s president, Alassane Ouattara, and the influential Beninese finance minister, Romuald Wadagni.

Tah has a degree in economy from the University of Nice-Sophia-Antipolis in France and one in agronomy from Morocco’s Hassan II University, as well as almost four decades in national and international finance.

In the late 1990s, he began gravitating towards the region that proved to be key for his further career and is likely to be crucial for the future of the bank he’s just been elected to lead: the Middle East – not least because of the large amounts of money it can mobilise.

The London bi-weekly Africa Confidential suggests that his excellent connections with the Gulf States and others in the region may well help him plug the $555m hole Donald Trump’s administration is leaving in the African Development Fund (the soft-loan arm of the AfDB Group), as a result of its overseas budget cuts.

It doesn’t mean the continent is “under attack from the US government”, Tah’s predecessor, Akinwumi Adesina, who spent a decade with the bank, told the Financial Times in April, right before Trump unleashed his tariff new world order. But it does mean the continent should adapt, he said.

“I can’t take your benevolence and put it on my balance sheet,” he said, speaking of the US’s swingeing cuts to aid. “Africa is not going to beg its way to development. It has to do so by trade and investment.”

The AfDB itself has access to more than $300bn in capital, mostly for infrastructure, power and agriculture projects.

Making his mark

Tah’s connections with Arab states span much of his career in banking. First, there was a three-year stint in the Sudanese capital Khartoum at a major rural investment and development agency and then a move to the Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Tah returned to Mauritania in 2006, becoming an economic adviser to both the president and the prime minister. He survived a coup in 2008 to become the country’s economy and finance minister, a position he held for seven years.

It was then that he really left his mark, setting up major reforms that greatly reduced inflation, cleaned up government finances and secured international assistance for big infrastructure projects in roads and electricity.

The institution that links Africa and the Middle East was his penultimate stop before landing in Abidjan: Tah spent the past decade heading the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa. During those 10 years he transformed it into one of the premier development banks on the continent by accessing funds lodged in the numerous sovereign wealth funds of the region, which helped quadruple its capital to $20bn.

He has big shoes to fill when he takes office on September 1. Nigeria’s Adesina oversaw a comprehensive reform process at the bank, held together by what became the “high five”, priorities the bank should live by: bringing electricity, ensuring food security, industrialisation, improving the quality of life for the citizens of this continent and advancing continental integration.

Tah will also have to take on the issue of climate change and the disruptions it brings to African economies, as well navigate the conundrum that plenty of African countries are rich in hydrocarbons, notwithstanding a big push towards renewables by Western financiers.

As Adesina told the FT: “Africa cannot be sitting on massive resources and [remain] poor. For me, it’s not negotiable. Africa doesn’t have access to electricity and yet is not allowed to use its gas.”

In short, the AfDB has to help African governments attract investments for industries that can transform those commodities on the continent instead of outside it.

It certainly has more capital to do so now: Tah’s predecessor increased capital at the bank from $93bn to $318bn. The new chief wants more financial injections and a faster project cycle, streamlining the workflows of the Bank’s bureaucracies.

The next five years will tell whether he can pull it off – and land this calm but determined financial technician a second term at the helm.

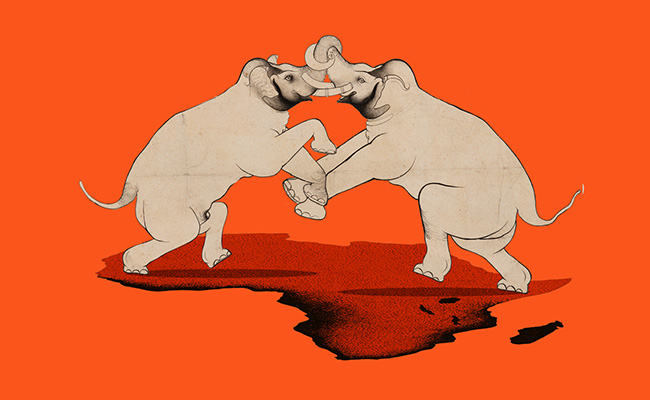

Top image: African Development Bank president Sidi Ould Tah. Picture: supplied.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.