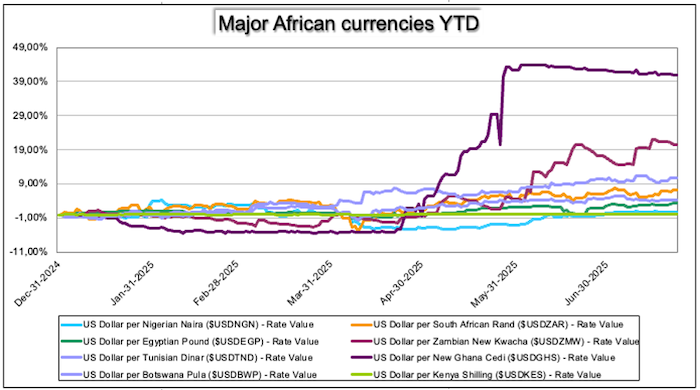

Here is a sentence you don’t hear often: year to date, every major African currency is up.

It is something of a rare moment in time. African currencies are notoriously “volatile”, and in this context, “volatile” most often means that they’re prone to dropping like a stone.

But since the start of this year, something dramatic has happened to African currencies; they have been surprisingly and shockingly undramatic. And this is true of currencies that are strongly managed, like the Egyptian pound; currencies that use a crawling peg system, like the Botswana pula; or those that trade almost entirely freely, like the rand.

The extent of the rise against the dollar this year is mixed, with the bigger economies particularly moving in a tight band. The Nigerian naira is up marginally against the dollar, the rand is up 7.3% and the Egyptian pound up 3.6%.

But some of the other currencies have moved up sharply. The new Ghanaian cedi is up 40% and the Zambian kwacha is up 20%.

Co-chief investment officer at Anchor Capital, Nolan Wapenaar, says this surprising turn of events is attributable mainly to two things: a weaker dollar so far this year, and quite a few rebounds from dramatic declines if you look a bit further back in time.

“Over a longer period, there’s been a big drop off in African currencies,” he says. Over a three-year period, not a single African currency other than the Tunisian dinar has registered gains against the dollar; the Egyptian pound is down 70% and the naira is down 60%.

These currencies reflect the problem of trying to manage a currency exchange rate, but it is significant that many African governments are moving away from this practice. The biggest offender here was the Nigerian authorities, but since President Bola Tinubu’s election in 2023, the country has been moving towards a crawling peg system, and results are beginning to show.

In a crawling peg system, authorities gradually adjust a country’s currency over time, with small, regular changes based on economic factors like inflation or trade. Theoretically, this method offers stability while allowing for flexibility, helping avoid sudden, large shifts in the exchange rate.

The naira is being supported by a “somewhat more market friendly government with a reformist attitude”, Wapenaar says.

The situation has been somewhat forced on Tinubu, who inherited a difficult situation from his predecessor. “But as a result of those policies, Nigeria’s been a bit of a market darling,” says Wapenaar, though whether that is deserved on a fundamental basis still remains to be seen.

Declining dollar

Because the dollar has weakened against the euro since the start of the year, that too has tended to make African currencies seem stronger against the dollar, whereas on a trade-weighted basis, they have probably slipped a bit.

“Generally speaking, you would expect African currencies to depreciate anywhere from 5% to 10% against the dollar over time. And most of them have done that sometimes a bit quicker, sometimes a bit slower,” says Wapenaar. The main reason for that is the inflation differential; the currencies of countries with high inflation rates tend to depreciate faster than those with low inflation rates.

But African inflation rates have fallen over the past year too, and that has tended to keep currencies confined to a holding pattern. A good example is the often-maligned rand.

The other issue is trade, which very recently has tended to favour African exporters. Oil dominates the exports of some African countries, notably Nigeria. But for the exporters of food, the terms of trade have been unusually favourable for African economies. Not to mention the strength of some commodities like gold, copper and platinum.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.