The best insights into the economic thinking of Paul Mashatile are often courtesy of his unscripted public debate over many years, whether in the National Assembly, media interviews or other forums.

Mashatile’s public appearances have always been highly choreographed, with speeches and remarks prepared by his staff before delivery. Nonetheless, they provide enough data to form an outline of what his economic theory could look like.

Mashatile seems to recognise that the private sector has a significant role to play in the economy and any effort to accelerate growth. But it is clear, however, that he will not break with ANC policy on state economic leadership.

“We are convinced that to build our economy, leaders from all sectors, including business, politics, government and civil society, must work together,” he told the African United Business Confederation last year. “It is our duty as political leaders in government to formulate policies that promote an environment conducive to economic growth [that] stimulate innovation.”

But in the same address, he added: “The ANC government will continue with the expansion of industries for an inclusive economy, revitalising the economy, and investing in people and micro businesses, particularly those owned by previously marginalised groups.”

Mashatile believes there are areas where the state and the private sector can work together beneficially – though it seems this will always happen at the behest and under the leadership of the government.

In 2023, he praised the collaboration between Business Leadership South Africa, Proudly South African, and the buy-local campaign as exemplifying “the dedication we seek from the private sector, where businesses continue to localise their supply and value chains” to expand industries in which South Africa has an advantage.

“It is still the state’s intention to support all industries that remain competitive, as well as those where capacity has been built up over the years, because of the designation of sectors for local procurement by the government,” he said.

During the electricity crisis, the private sector implored the government to allow it to assist the state in mitigating the effects of power shortages.

At the height of the power crisis in July 2023, Mashatile said that Gwede Mantashe, the minister of minerals and energy, had been “engaging” within businesses to find a solution.

“Allowing private developers to generate electricity is one of the country’s significant reforms. In this regard, there are already over 100 projects under way, with a total capacity of over 9,000MW planned to be added over time,” he said.

Companies in the renewable energy programme were about to build 2,800[MW] of new capacity but, to deal with the crisis, “Eskom will acquire emergency power that can be installed in the near future”, he said.

At the time, Mantashe had to be forced by Ramaphosa to remove the limit on the amount of electricity that private power producers could generate – and that was only because the country was facing disaster.

No softening of BEE

Mashatile is deeply committed to BEE as a cornerstone of ANC and government economic policy.

Despite the current debate about BEE’s effectiveness in producing fundamental economic change, it is clear that Mashatile will not veer from the course set by his predecessors should he become party leader and head of state.

Broad-based black economic empowerment (B-BBEE) is not only part of the ANC government’s DNA, it is also part of the foundation of ANC and patronage politics.

During state capture, BEE and preferential procurement became the fig leaf behind which networks of extraction could construct the scaffolding of large-scale corruption – to benefit only a few. No ANC leader will discard BEE as policy.

In fact, since Mashatile’s appointment as deputy president he has been strident in his assertions that BEE regulations and laws need to be refined and more firmly implemented.

His public statements are transparent: he wants stricter and narrower BEE laws to ensure economic activity is more regulated in favour of black participation.

“There is a more pressing need to support aggressive means and forms of economic integration for black-owned firms, particularly in the historically untransformed sectors of the economy,” Mashatile said at the Black Business Quarterly Awards ceremony in 2024.

He said the government must “pay close attention” to creating a regulatory environment that supports the informal economy. “The government’s efforts to restructure the economy through the B-BBEE policy, legislative framework and other interventions have made progress, but further efforts are still required.”

Mashatile said the success of black entrepreneurs represents the attainment of economic freedom, after political freedom in 1994.

“Despite the obstacles encountered since the passage of the B-BBEE Act two decades ago, our government remains unwavering in its mission to enhance and broaden economic empowerment and inclusion across all sectors.”

At a discussion after this year’s budget was tabled, Mashatile said that while the ANC took political charge of the country in 1994, it had not taken charge of the economy. This was revealing of his commitment to the primacy of the state in the economy and society.

“For the first 15 years of the country’s democratic rule, the economy grew at a rapid pace. However, over the past decade-and-a-half the country’s economy has been marked by slow growth,” he said.

Mashatile linked this to research published by the JSE in 2013, which said there was only 10% Black ownership directly, and 13% indirectly, through institutional mandated funds.

These numbers are “indicative of a lack of structural reform, which has led to the continuation of ownership patterns that remain in white hands”.

That was not good enough, he said, and the government should intervene.

Mashatile said that three decades after the end of apartheid, the economy is still characterised by high levels of poverty and inequality, despite policy interventions like the Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment Act.

“Evidently, without the introduction of critical structural and transformative policies such as B-BBEE, the economy will still largely be white and, in particular, white male dominated,” he said.

Structural transformation has “remained stubbornly elusive”, he said, adding that this “necessitates continuous intervention” and “the rigorous implementation of policies that are designed to, among other things, cultivate black industrialists”.

This would increase the participation of black individuals in the entire value chain of the economy, he said.

These themes recur whenever Mashatile speaks at award dinners or gatherings of black businessmen – but they are conspicuously absent when he speaks in other formal settings, such as investor meetings at Goldman Sachs in London or the London Stock Exchange.

Of course, the emphasis will change for different audiences, but if BEE is a crucial part of ANC economic thinking and dogma, the party and the government it leads should be able to articulate it on every stage.

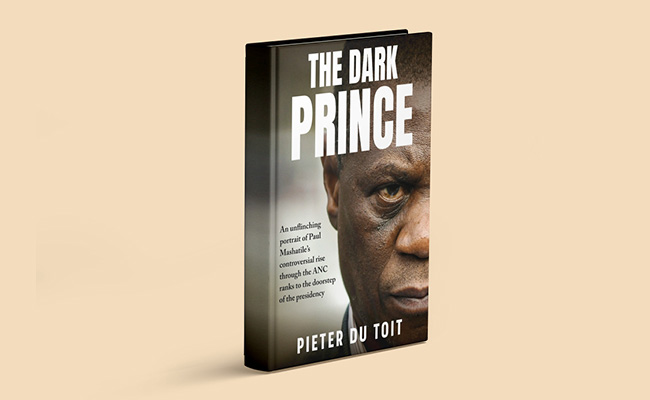

Pieter du Toit’s ‘The Dark Prince’ is published by Jonathan Ball.

Top image: Deputy President Paul Mashatile. Gallo Images/Darren Stewart.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.