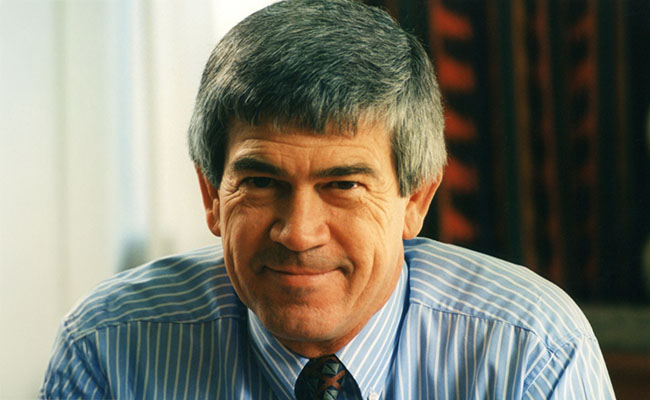

One of the most often-told stories about mining entrepreneur Brian Gilbertson, who died last month at the age of 82, is also the most miscued: the famous story about the ego landing.

Almost inevitably, the sparse and formulaic obituaries written about Gilbertson over the past month can’t help but mention the story, which was first noted years ago in The Economist: staff would greet Gilbertson’s arrival by helicopter on the roof of Gencor’s headquarters in the heart of Joburg by declaring that “the ego has landed”.

Yet, by all accounts, Gilbertson was not egotistical in the formal sense; but he was self-assured, very certain, visionary and, most of all, a fiercely independent-minded outsider. And those qualities were on dramatic and full display at the two key moments of his life: the reconfiguration of Australian mining giant BHP and his departure from it.

Several people who knew him well – well enough to know all aspects of his complex character – are still a bit bemused by this characterisation of Gilbertson, whom they describe as kind, polite and generous. He certainly never talked about himself in the way an egotist would. But, they add, he was never “warm and cuddly” and could be distant, quick to smile but always with a cool demeanour. “People were in awe of him,” one former colleague said.

In fact, there is an enormous irony behind the characterisation of Gilbertson as “egotistical” because, oddly enough, his deposition from the merger he oversaw just 180 days after it was consummated was much more the direct consequence of the egotism of the then company chair, Don Argus, who also had a nick name. His was “don’t argue”.

A mega-merger

As it happens, the creation of the merger between Billiton and BHP in 1999 is now swept away in Australia, and South Africa for that matter. The Australian Financial Review acknowledged Gilbertson’s contribution in conceiving of the merger, but it noted that perceptions had grown over time that it had served Billiton shareholders better than BHP’s. “By 2015 most of the Billiton assets were providing little value and were demerged into South32,” the paper noted, pointing out also his “rocky” relationship with the Australian business community.

Possibly. But there is still an argument to be had about Gilbertson’s role, because at the time BHP was emerging from a series of investment setbacks and was very much in danger of losing its title as “the big Australian” to its long-time rival Rio Tinto. There is no doubt that the reconfiguration of BHP, including some young talent from Billiton, a fresh approach and a new management, ultimately strengthened the company.

The deal was preceded by the creation of Billiton itself out of the morass of oil company Shell’s mining assets, which was a truly astoundingly good deal for Billiton shareholders. The subsequent deal that never happened was the proposed merger of Rio Tinto and BHP, designed specifically to create price-bargaining power and production synergies in the Pilbara region where both companies operated.

Typically, Gilbertson just did what he thought was the right thing and do it fast, as his long-time mentor Derek Keys had taught him. That independent streak again. So no sooner had one huge deal – the largest mining deal at the time – been consummated, than he started negotiating with Rio, aiming of course to inform the board when a loose meeting of minds had been achieved.

The blockbuster deal that wasn’t

It would have been an absolute blockbuster of a deal, but like all huge deals, it would have had complications. It might have meant that BHP would have had to sell its oil assets, which constituted about 30% of its earnings at the time. It might have meant moving the head office to London, which would have suited the urbane Gilbertson down to the ground. And it might have meant moving BHP’s centre of Australian operations out of Melbourne to (OMG!) Perth.

All three were just frightening to the Australian-dominated board of BHP at the time, and they freaked out, summarily booting Gilbertson out as CEO, citing “irreconcilable differences”.

But here are the many ironies: first, BHP did ultimately sell its oil business to Woodside in 2021. BHP did in fact build a huge new headquarters in Perth, now the city’s largest building, right next door to Rio’s Western Australia headquarters. And BHP did try to merge with Rio a few years later – a merger attempt that failed, really, because the iron ore explosion had taken place by this time, and competition authorities around the world would probably have looked at it askance.

The deal needed to be done when Gilbertson conceived of it, by a dealmaker with a great record – that is, Gilbertson. But it was scotched by a chair and board whose collective egos were piqued about being left out of the early negotiations. What can you do; little men are everywhere.

As it happens, it probably didn’t make much difference, because conveniently for both BHP and Rio, the iron ore price just exploded on the back of Chinese and Asian economic growth shortly afterwards, and both companies have not looked back since. Such are the vagaries of the mining business.

The big secret

But there is one coda to this story: Gilbertson never told anyone the real cause of his ousting, for years and years. Of course, nobody inside Rio or BHP did that either, but they had a big incentive to not tell anyone – they would get fired. Gilbertson had been fired already, but he might have gained in status in the corporate world based on the sheer audacity of the proposal – and locked a bit of retribution for the small-mindedness of his opponents.

A more egotistical man than Gilbertson might have bypassed the inevitable information lock-up imposed by BHP and leaked the story to, say, a big London-based financial publication. They certainly asked him. But he never did. He went for a long walk in Tasmania and kept his own council.

A bit later, the Australian Financial Review made a solid attempt at describing the breakup, and it did hint at the deal. But nowhere was it definitively specified – not in Australia, South Africa or London. In some senses, this fact is a kind of inverse hat-tip at Gilbertson’s vision; it was so audacious that nobody outside the organisations could really get their heads around it.

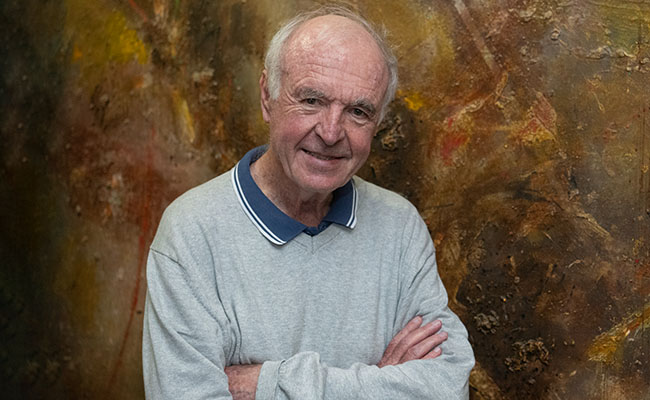

After BHP, Gilbertson never quite found a second act to match the first. He remained active – chairing companies, pursuing private ventures, advising internationally – but the scale was inevitably smaller. Having already executed one of the largest mining mergers in history, there was no obvious encore. Some later ventures were structurally flawed, and others appeared motivated as much by personal loyalty and legacy as by cold strategic logic.

Outsider status

The root fact is that Gilbertson was never an insider. Born into a modest Free State background and educated at Rhodes University, he did not carry the social markers that defined South Africa’s traditional mining elite, nor later the Australian corporate establishment he would encounter at BHP. He didn’t even study mining engineering – he was literally a rocket scientist. That outsider status shaped almost everything about him: his management style, his alliances, his appetite for risk, and ultimately the resistance he provoked.

Even so, his standing in South African corporate history remains exceptional. Few executives from the country have not only operated successfully on the global stage, but reshaped it. Alongside figures such as South African Breweries CEO Graham Mackay, Gilbertson belongs to a very small group of South African corporate leaders who did not merely export themselves, but exported an entire corporate vision.

His obituaries describe him as a visionary. But the fuller picture is more interesting than that word suggests: a brilliant, difficult, sometimes demanding outsider whose greatest strength – his refusal to conform – was also the reason his reign at the top ended sooner than it might have.

Gilbertson’s legacy is not just the companies he built, but the reminder that transformative leadership rarely fits comfortably within established institutions.

Top image: www.online-tribute.com/BrianPatrickGilbertson.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.