If there is a critical new discussion taking place at the Mining Indaba in Cape Town, it’s about critical minerals. But even the definition of “critical minerals” is a movable feast, and it varies from country to country.

Mineral and petroleum resources minister Gwede Mantashe said during his official opening address at the indaba: “The global scramble for minerals has entered a more aggressive phase, driven by strategic priorities in developed economies seeking to reduce dependence on external suppliers.”

But Mantashe added that he had come to the conclusion that every mineral is critical because all products were originally either grown or mined.

However, his extremely broad definition is not the technically accepted one. More formally, “critical minerals” are all minerals and metals that are considered essential to a country’s economic or national security, and whose supply chains are vulnerable to disruption. Or to put it another way, they are minerals of high economic importance where there is a high supply risk.

That will differ from country to country, but the commonly classified critical minerals include lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, nickel, graphite, gallium, germanium, platinum group metals (PGMs), manganese (in some jurisdictions) and some forms of titanium. Though they are “critical”, gold and iron ore, for example, are not considered critical minerals because supply chains are broad and liquid.

Intra-continental tensions

A quick glance at that list demonstrates how important Africa is to the category. Just for example, the vast majority of currently produced cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and both PGMs and manganese are abundant in South Africa.

The subject of Africa’s approach to critical minerals was a contentious issue at the indaba, with Mantashe urging African countries to avoid a “race to the bottom” and to “talk with one voice”.

The Daily Maverick reported that Mantashe clashed with his Congolese counterpart at a closed ministerial meeting at the indaba, going so far as to accuse the DRC of “selling out [to the US], or words to that effect” on critical minerals.

Later, at a discussion that included the two ministers, DRC mining minister Louis Watum Kabamba defended the DRC deal, saying it was not one-way and the country had not sold its minerals for nothing. He said the DRC was looking after its own national interest by diversifying its partners, noting that China had been dominating the purchase of African copper production, for instance.

Tariff tit-for-tat

The whole issue of critical minerals exploded into public consciousness when it became apparent that US President Donald Trump had been forced to pull back on his tariff escalation plan against China when the world’s second-biggest economy introduced export controls on several rare earth elements last October. These curbs were widely seen as retaliatory against US tariffs and had the potential to disrupt supply for industries that rely on them.

Both sides gradually de-escalated the dispute, and by November, shipments of rare earth elements from China to the US were reported to have increased again following the agreement, indicating that the earlier export controls were no longer causing the same disruptions.

But just the fact that China could successfully use rare earth elements as a negotiation tool opened a window on the concept, sparking frantic fresh efforts to build new mines around the world, some heavily backed by US funders, to make up the shortfall.

So, now the question at the Mining Indaba from the point of view of global politics focuses on two questions: which critical minerals are the most critical, and how long will it take for the countries that don’t have them to secure them?

The question doesn’t only have to do with mining, because the one well-known thing about rare earth elements is that they are not geologically rare, and can even be recovered from coal ash and industrial waste streams. Economically viable extraction and especially separation, however, remain technically complex. And the trick is not only availability but also refining capacity, which in the case of some of the elements, is extremely difficult.

China’s dominance

For places like the US and Europe, the problem minerals elements are in fact a subset of rare earth elements, called heavy and medium rare earths, including some few people have ever heard of: yttrium, ytterbium, holmium and terbium.

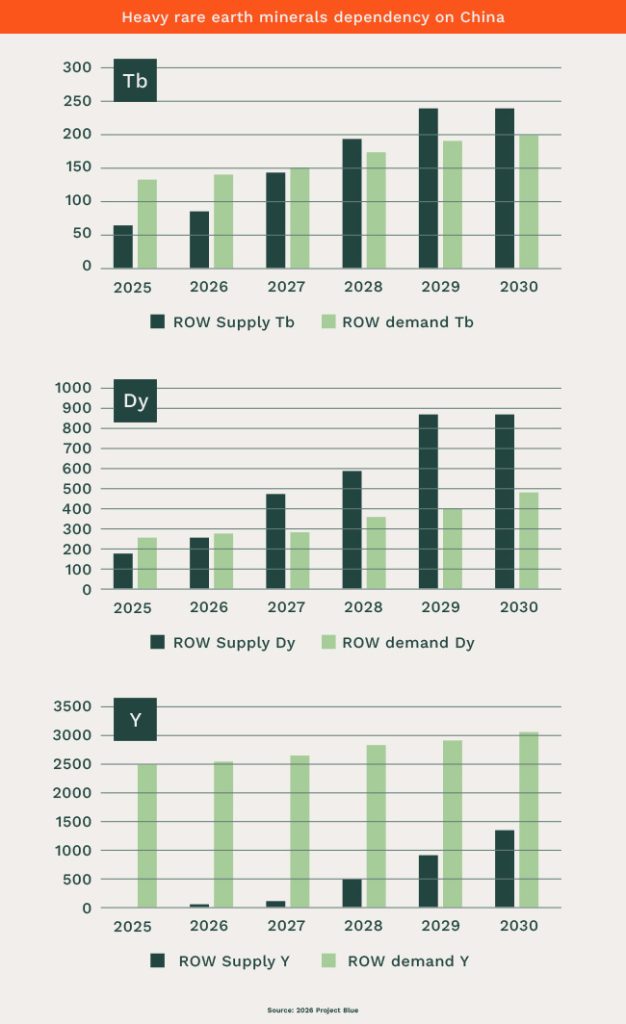

A presentation at the indaba by geological consultancy Project Blue looked in depth at critical minerals in general, but also at three of these heavy rare earth elements: yttrium (Y), dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb).

It came to the conclusion that the project pipeline outside China is expanding, but that China is expected to retain dominance in heavy rare earth processing into the 2030s.

These rare earths are crucial for most powerful permanent magnets, essentially because at high temperatures magnets lose magnetic strength. Adding small amounts of dysprosium and terbium increases their resistance to demagnetisation. The crucial use of these powerful magnets is in electric cars and, consequently, much of the shortage is driven by the increasing global market share of electric cars.

And that demand is very dependent on the attitude of developed economy governments towards climate change and the electric car industry. Founder and director of Project Blue Nils Backeberg said at a presentation on the periphery of the Mining Indaba that the regulatory policy frameworks remain a core driver for the electric vehicle (EV) industry in the short to medium term.

In key regions around the world, EV sales are increasing fast, with lots of room to grow. About 50% of the new car market in China now consists of EVs, about 20% in Europe, and 10% in the US.

“In the world of geopolitics that we live in today, with policies being volatile, this is making this quite a complicated landscape to navigate, especially looking at investment opportunities and potential threats,” Backeberg said.

ALSO READ:

- Claiming the ground beneath the elephants: Africa’s new geopolitical challenge

- White-hot platinum

- Mantashe speaks ‘growth’ amid regret at South African mining’s ‘lost generation’

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.