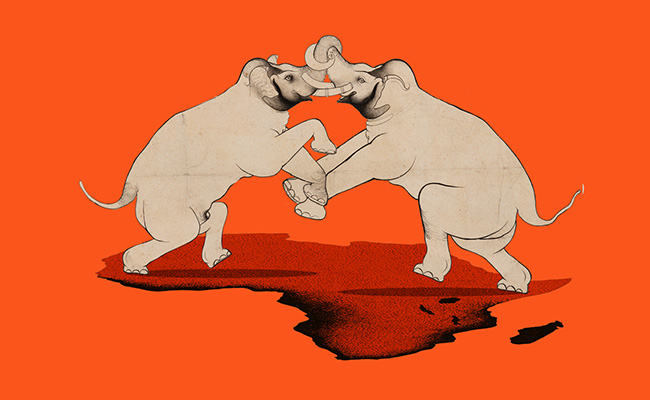

“Ndovu wawili wakisongana, ziumiazo ni nyika.” When two elephants fight, it is the grass that is hurt.

The Kiswahili proverb, popularised by Julius Nyerere during the Cold War, was meant to capture the fate of small states crushed between rival great powers. The elephants then were Washington and Moscow; the grass was much of the developing world. The metaphor remains painfully relevant today, even if the elephants have multiplied and the battlefield has expanded.

Africa finds itself once again in a geopolitical maelstrom. The war between Russia and Ukraine grinds on with global consequences. The conflict between Israel and Palestine continues to destabilise the Middle East. Sudan is imploding. Sanctions are being weaponised, tariffs turned into instruments of statecraft, leaders of sovereign countries are abducted across borders, and scenes unfold in major American cities that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. Globally, instability is not only high; it is structural.

On this stage, small and mid-sized countries are the grass: vulnerable to trampling, and collateral damage in conflicts not of their making. Yet history tells us something more uncomfortable and more hopeful. Small countries are not only vulnerable; they are also strategically valuable. And today, that value has less to do with where the ground is located than with what lies beneath it.

From geography to geology – and beyond

For centuries, Africa’s strategic importance was largely geographic: sea routes, choke points, proximity to trade corridors. That has not disappeared, but it has been eclipsed by a deeper contest. The great powers are now locked into simultaneous energy and digital transitions. Electrification, decarbonisation, AI and data infrastructure all depend on physical inputs that cannot be conjured by software or finance alone.

Those inputs sit, disproportionately, beneath African soil.

The continent holds an outsized share of the world’s critical minerals: platinum group metals, manganese, copper, cobalt, lithium and rare earth elements. The Southern African region alone accounts for close to 30% of known global reserves of some of these materials. These are not marginal resources. They are foundational to batteries, electric vehicles, grid infrastructure, hydrogen production and advanced electronics.

But the “ground beneath the elephants” is no longer only ore. It is also cables and corridors, ports and pipelines, fibre landing points, satellite ground stations, spectrum rights and data centres. It is human capital: a young population that will form the global workforce of the energy transition. In this sense, Africa is not merely resource-rich; it is infrastructure-strategic.

The leverage – and the trap

This position creates the possibility of unprecedented leverage. But it also reopens an old trap: the resource curse. Africa has been here before. Abundant natural wealth has too often translated into dependency, corruption and underdevelopment rather than prosperity.

What makes this moment different is not moral awakening but structural pressure. Supply chains are fragile. Energy transition timelines are compressed. Western governments face ESG scrutiny. China’s balance-sheet diplomacy is more constrained than it was a decade ago. Buyers need speed, reliability and legitimacy as much as volume.

The real risk, therefore, is not extraction itself – it is extraction without co-ordination.

Acting en bloc – or not at all

Africa’s historical track record of collective action is, at best, uneven. Yet there are frameworks that could be activated rather than reinvented. The AU has articulated a vision in which mineral wealth underpins industrialisation rather than extraction alone. The Africa Mining Vision and its action plan explicitly aim to ensure that the minerals sector drives inclusive growth, local beneficiation and sustainable development.

Within this framework lies a crucial strategic shift: buyers should increasingly acquire finished or semi-finished products, not raw materials.

How might this work in practice? One route is through regional economic communities such as the Southern African Development Community, the East African Community and the Economic Community of West African States. These blocs already map trade relationships, harmonise standards and provide platforms for collective negotiation.

Another, more targeted approach is mineral-specific co-operation. South Africa and neighbouring Zimbabwe command close to 80% of global platinum reserves; South Africa holds roughly 77.5% and Zimbabwe has the balance. Copper production spans the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia and several other African states, amounting to about 6% of global reserves. These are not trivial numbers. When aggregated, they confer real bargaining power.

This does not require cartel-style price fixing. More realistic mechanisms include shared royalty floors, co-ordinated export licensing, common environmental standards, standardised contracts and joint marketing platforms that reduce information asymmetry between multinational buyers and small states. The aim is not confrontation but coherence.

Strategic non-alignment, redefined

None of this happens in a geopolitical vacuum. The US, EU and China are not neutral economic actors. Each brings security expectations, regulatory spillovers and political conditions. Africa’s challenge is to avoid exclusive alignment without lapsing into passivity.

Strategic non-alignment today is not sitting on the fence. It is building optionality – multiple doors out of the room. It is diversifying partners, sequencing commitments and resisting long-term bilateral deals that lock strategic assets into inflexible arrangements.

Africa’s leverage extends beyond minerals. It includes voting power in multilateral institutions, climate legitimacy as a continent that did not cause the crisis but is essential to solving it, peacekeeping capacity that underwrites global security, and the simple fact of being a future consumer market of scale.

The cost of failure

The alternative is sobering. Fragmentation would invite a race to the bottom in tax regimes, a scattering of under-scaled beneficiation projects, and the quiet enclosure of strategic assets through long-term contracts signed under fiscal pressure. Digital colonisation would replace resource colonisation, and the ground beneath the elephants would once again belong to someone else.

Elephants are the largest animals in the bush, but size alone does not guarantee victory. In the children’s story The Elephant and the Ant, intelligence and co-ordination matter more than brute force. For Africa, survival – and thriving – will not come from neutrality or nostalgia. It will come from agility, alignment and reinvention.

In a world of stomping elephants, Africa does not need to be louder or bigger. It needs to be smarter about the ground it stands on – and relentless in claiming what lies beneath it.

Tamsin Freemantle will be hosting a panel at the Mining Indaba on Wednesday February 11 at 10am. The session looks to address financing across the full gold project life cycle, funding early-stage exploitation through production, and the next wave of African gold producers.

ALSO READ:

- ‘Resource nationalism’ raises mining risk

- Guns, cobalt and sons-in-law: Trump’s shadow diplomacy

- Is Africa about to miss its golden moment?

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.