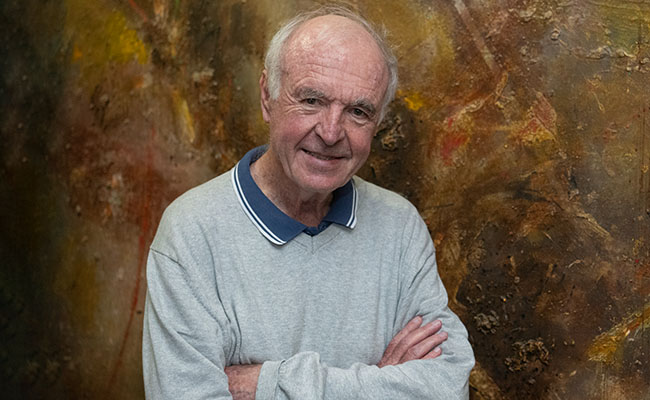

“Things have honestly changed more in the last five years than they have in the last 125 years,” says Donald Greig of the luxury jewellery brand Charles Greig.

Jewellers have been in the centre of the maelstrom. On the one hand, the gold price has rocketed 110% over the past three years; on the other, diamond prices have tumbled about 35% over that the time. The upshot: fine pieces remain expensive to produce, but aren’t as valuable as they once were.

There are several roots to this, including a slowdown in luxury sales in China in recent years, a country where the diamond jewellery market was once booming. But nothing has been quite as ruinous as the rise of lab-grown diamonds.

“Lab-grown diamonds have collapsed the whole diamond market globally, and it’s not something that’s going to recover,” Greig says, seemingly resigned to the finality.

But the data reinforces his grim prediction. Currency reported last year that lab-grown diamonds accounted for 14.3% of all diamond sales in 2023 – and that figure jumped sharply to 20% in 2024.

Lab-grown diamonds are far cheaper to produce, even though they are molecularly, chemically and optically identical to natural diamonds. And, because they are produced industrially, supply is endless – puncturing the myth of diamonds as rare.

Diamond producers are feeling this devastation in their pocket.

The government of Botswana, which gets a third of its annual revenue from diamond sales, has warned that its joint-venture mining business, Debswana, will see a staggering 40% fall in output in 2025. De Beers, which owns the other 50% of Debswana, was forced to shed more than 1,000 jobs at the company in May.

“This model has reached its limit,” Botswana’s President Duma Boko said last month. “This is no longer an economic challenge alone; it is a national social existential threat.”

Jewellery giants like De Beers, once a hugely profitable part of Anglo American, have lost their relevance and value in the past decade, unable to compete with the mass production of lab-grown diamonds. Keeping the dream alive in the face of all this is a brutal task.

Anglo American still owns 85% of De Beers, but has been itching to sell it. In February, it slashed the value of that stake by $2.9bn, bringing its total write-down to $4.5bn. No wonder, as De Beers made a $189m loss in the first half of 2025.

The once-dominant jewellery brand made a confused lurch into the lab-grown sector too with its own brand, Lightbox, positioning it as a low-cost trendy alternative to expensive natural diamonds. It was a disaster, only serving to confuse and cannibalise De Beers’ core business, so it quietly ditched that plan.

It’s not the only one. Fabergé, the luxury brand known for its bejewelled eggs, was also sold by the miner Gemfields last week to SMG Capital for $50m – a sharp drop from the $142m that Gemfields paid for Fabergé in 2013. Fabergé has also faced a loss of prestige in the face of the diamond crisis, and in a luxury market in flux.

“Mining companies are experts in supply, not in luxury branding,” says gemmologist Tim Watson. “Success in jewellery retail depends on heritage and craftsmanship – strengths of established international brands like Cartier or Van Cleef & Arpels. This is why miners have stepped back from luxury ventures and concentrated on their core expertise.”

Forever needs a facelift

The diamond downturn is, to some extent, a marketing issue.

Consumers are no longer so easily fooled by slogans such as “A diamond is forever”, and economic pressures coupled with concerns around the ethics of diamond mining mean it won’t be an easy market to swing back around.

To protect their businesses, most luxury jewellers refuse to work with lab-grown diamonds, while furiously extolling the virtues of natural diamonds.

This underscores the fact that the most powerful advantage that natural stones possess is their narrative, their connection to the earth’s formation. Marketers have argued that the millions of years taken to create a natural diamond is a metaphor for family legacies.

“Jewellery has strong emotional and sentimental value,” Watson says. “It commemorates special life events, represents status and self-expression and continues to be seen as an heirloom.”

And while colourless, high-quality diamonds have lost their value, Greig says coloured diamonds – far more difficult to synthesise – have held their value and are becoming increasingly valuable. Champagne and yellow-coloured diamonds, once outcasts, are now marketed as inimitable – a show of what the earth can do that machinery cannot.

After diamonds

While the diamond industry is struggling, other gem miners and jewellers have retained their value. Greig says precious stones such as rubies, sapphires and emeralds are “still very collectible and sought after, with a huge demand”.

In fact, the rise of coloured gems is directly linked to the challenges the diamond industry faces, stone dealers say, as consumers are seeking out a luxurious alternative to diamonds.

Miners are feeling this upswing too. Gemfields will use the proceeds of the Fabergé sale to expand its gemstone business: partly for its new processing plant at Montepuez Ruby Mine in Mozambique, and partly to extend its Kagem Emerald Mine in Zambia.

Watson says international tourists remain captivated by the rich, distinctive colours of gemstones mined in Africa, such as tanzanite, tsavorite and tourmaline, and are willing to pay high prices for these rare gems.

Luxury jewellery and gemstones are also seeing an uptick on the antique market, where unusual and limited-edition pieces are selling for millions.

Kim Goeller, a jewellery specialist at auction house Strauss & Co, explains that people are increasingly turning to the vintage market to get into luxury jewellery.

“Brand names will stand the test of time and buying a Rolex watch or a Van Cleef & Arpels necklace on auction is the most affordable way to enter the big brand market,” says Goeller. “These items hold their value and desirability. Some pieces are no longer available at retail level, and their [desirability] factor soars even further.”

Goeller says young couples are increasingly choosing engagement gems on auction.

By going vintage, clients can enjoy high-quality artistry without worrying about their contribution to continued gemstone mining, which often comes with ethical concerns around labour exploitation and environmental damage.

The rarity of vintage items also makes them sound financial investments, as their pieces increase in value as they become harder to find.

But the reality that people will now choose a historic signet ring, say, over a new diamond is telling of the state of the luxury jewellery market. Miners, jewellers, and consumers alike are all looking for the next big thing – and it’s not diamonds.

Greig believes this slide will hit even the most globally established brands. Looking at the swanky diamond stores on Bond Street and Fifth Avenue with their massive, polished stones, he can’t help but wonder: “Where is the value on something like that heading?”

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

It is justice on criminal activities that was supposedly started under philanthropy. Stripping assets from a country for own benefit.

Thank you Mr C J Rhodes.

Natural diamonds are so common. To compete with the lab grown market, its time the price of natural diamonds were adjusted accordingly. This will lead to a quandary as to what stone to buy. As for myself, I prefer natural.