The celebration over Eskom’s first profit in eight years this week was surprisingly muted for a company that was on its knees, and had the country on its knees, a few months ago.

Yet on Tuesday, Eskom CEO Dan Marokane revealed that the utility had, against the trend, reported an after-tax profit of R16bn – an unthinkable result for a company that until last year couldn’t keep the lights on, and which clocked up total losses of R159.5bn over the previous seven years.

“Our recovery programme is a journey,” said Marokane in an interview. “At the right levels of debt, and the right performance operationally, this business should be able to wash its face.”

Well, yes, given the prices it charges households, you’d think it could – but that is something it manifestly hasn’t done for years. And it has cost the country hugely.

Marokane quantified the damage to South Africa from the “absence of a reliable power supply” last year at an astounding R2.8-trillion. “That number has come down to some R480bn, so a functional Eskom that is sustainable is important for the country,” he said.

No kidding. The loss of R2.8-trillion is an unfathomable number, and a serious bite out of South Africa’s wheezing GDP. Extrapolate that over the 16 years of blackouts, and you can see how the country’s economy would be in a completely different place, but for this debacle.

“We have to appreciate the strides made in moving us from that point to where we are now,” said Marokane. “We ought not to have been there in the first place, but it is when we did not have the power that we begin to appreciate the importance of having a [sustainable] utility.”

And the turnaround is impressive. In whole numbers, to go from a R55bn loss to a R16bn profit is a R71bn turnaround. To put that in context, last year’s loss was equal to nearly R1,000 for every South African.

So how is it that Eskom, depicted a decade ago as an unfixable basket case likely to drag South Africa to failed-nation status, made such a reversal?

In a nutshell, the answer is: more electricity to sell, less expensive diesel being burnt, and then, critically, a 12.74% tariff increase. Oh, and a saving of R5bn in interest payments, thanks to National Treasury taking over a large chunk of its debt.

All of this was laid bare when CFO Calib Cassim stepped up to present Eskom’s numbers at the results presentation.

This showed that Eskom’s primary energy costs dropped 14% to R150.2bn (less diesel being burnt), its sales rose 3.5% to 189.7TWh (a higher energy availability factor, or EAF, approaching 70%), which pushed its revenue up by R45bn to R340.9bn.

Little matter that it only actually hit an EAF of 70% for three weeks this year, it’s still going in the right direction at least, for the first time in ages.

Time to eat

So does this profit now mean that Eskom can stop dipping its proboscis into your pocket as frequently as before? Now that its price hikes have tipped so many people over their household fiscal cliff, will this be the end of that particular cycle?

Mercifully, Marokane suggests it may just be.

“We have heard the plea of South Africans in as far as the cost of electricity [is] concerned going forward. We are planning on a business model that will have to survive on a single-digit increase in the price of electricity going forward,” he says.

It’ll have to do this by cutting R50bn in cost, selling more electricity, and cutting out the corruption and waste that has made Eskom a byword for self-dealing.

This is clearly a talking point that Eskom wants to drum home. On a PSG webinar after Eskom’s results, chair Mteto Nyati echoed Marokane’s promise.

“We should not be able to see tariff increases that are above consumer price inflation,” he said. “They need to be single digits, very much in line with everything else in society.”

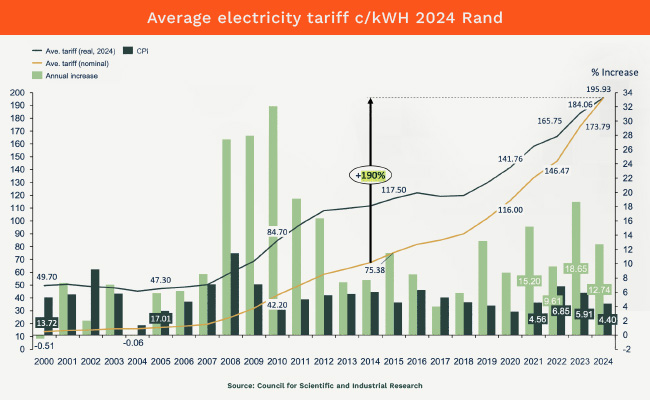

This would be a big deal, since Eskom’s tariffs have risen by an average of 10% a year over the past decade, roughly double the average 5.2% over that time. A Council for Scientific and Industrial Research report that Marokane mentioned confirmed that power prices soared 190% since 2014.

Before 2008, it said, power prices were mostly below inflation. Load-shedding, and immense spending on Medupi and Kusile, changed this dynamic entirely.

Before this year’s 12.7%, last year the prices rose 18.6%, then 9.6%, then 15.2%. That’s a lot of feeding at the trough.

Still, it remains to be seen if Eskom can keep to its word, given the new, new migraine it is facing: South Africa’s corrupted municipalities.

At last count, municipalities around the country owed Eskom R103bn. Even the City of Joburg, the country’s economic hub, which has been run with the sort of attention to detail of a nursery school art class, wasn’t paying its power bills.

“You are looking at about R125bn come the end of the year, maybe even as much as R130bn, which is unsustainable,” says Cassim. “What we do say, at this trajectory, is that by the time you get to 2030, this number could be well above R300bn, which will nullify the R230bn in debt relief support [given by National Treasury].”

This, Cassim says euphemistically, is the “biggest area we need to address”.

It is also a risk to Marokane’s pledge to keep down the costs for those consumers who do pay their bills. A massive debtors book means that as much as Eskom might not want to hike prices again to cover the hole in its balance sheet, it might just have to.

Top image: Eskom CEO Dan Marokane. Picture: Gallo Images/Lubabalo Lesolle.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Rob,

If Eskom had to impair its debtor’s book according to IFRS, it would have been a different story. Does anyone see a lignt at the end of a disfunctional local government tunnel?

I wouldn’t be holding my breath for them to keep this up. Let’s be real—whenever the government gives itself a pat on the back, it’s usually a one-way ticket back to business as usual… aka, the loot train rolls on!

Muted celebration is not surprising if you consider the report given to Parliament on 16 October by the Auditor General: “Eskom’s overall audit outcome remains similar to the prior year due to qualifications on

the disclosed irregular expenditure (completeness and accuracy) and losses due to criminal conduct (completeness).” The AG presentation to Parliament (on the Parliamentary Monitoring Group website) is worth reading.