A number of South African wild animal exporters have been supplying animal import companies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with birds and animals, despite questions over whether this has been done in compliance with the global treaty governing wildlife trading.

Some of these animals are re-exported to Vantara, a 1,200ha area adjacent to a huge oil refinery in Jamnagar, India, which is billed as the world’s largest zoo, with an animal population running into the hundreds of thousands.

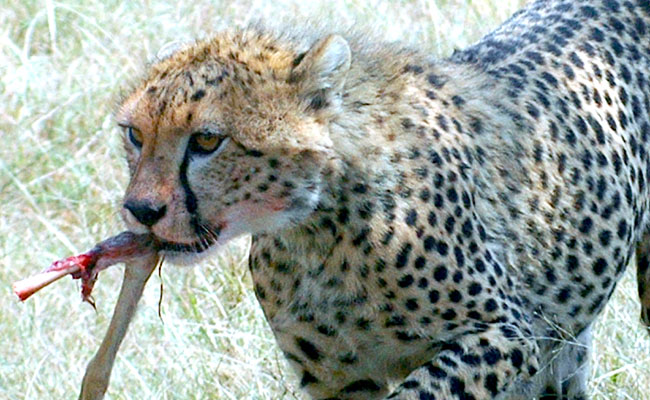

Yet the evidence obtained in this investigation shows that South African companies appear to be shipping endangered wild species directly to Vantara, including leopards, cheetahs, tigers, African grey parrots and Scarlet macaws.

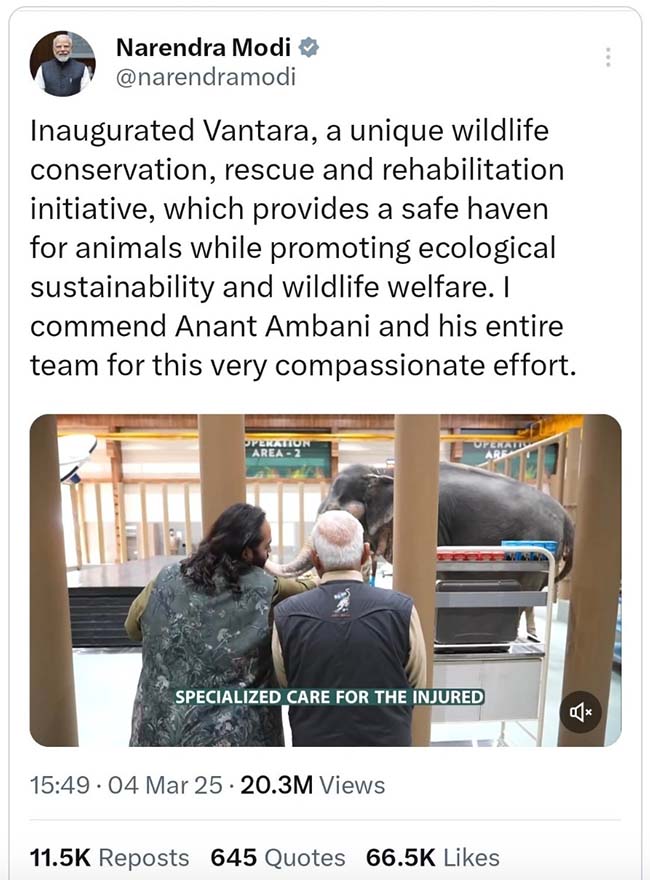

This compounds the controversy over Vantara, originally known as the Greens Zoological Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre, which is the brainchild of Anant Ambani, the son of petrochemical billionaire Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man.

Last week, India’s Supreme Court ordered an investigation into claims that animals were being bought illegally, that wildlife laws were being flouted, and that this involved financial irregularities and possible money-laundering.

This will be a blow to a family with a reputation for living large: its home in Mumbai is a 27-storey building, and Ambani gets around in a Boeing 327 Max. Anant’s three-day wedding last year – billed as India’s “own royal wedding” – cost an estimated $600m.

But despite the allegations that Ambani has bent the rules in building his mega-zoo, he claims that “Vantara is a combination of the age-old ethical value of compassion with the excellence of modern scientific and technological professionalism”. Last year, he said animal care is a selfless service towards “the almighty as well as humanity”.

Yet investigations suggest a number of South African exporters, and an obscure animal shelter and zoo in the Abu Dhabi desert town of Al Ain in the UAE, have supplied thousands of exotic animals to Vantara using questionable sourcing practices.

The UAE entities – the Kangaroo Animals Shelter Center (KASC), and the Capital Zoo and Wildlife Park (CZWP) – are owned by wildlife trader Khaled Aldhaheri, and have supplied more than 7,800 animals of protected species to Vantara.

Both KASC and CZWP were unknown before February 2023, when KASC made its first shipment of exotic animals to Vantara, followed by the first shipment by CZWP in February 2024.

Aldhaheri appears to operate through three commercial animal trading companies in Abu Dhabi: Kangaroo Animals Trading, Kangaroo Est and Ekat. Kangaroo Logistics is an Aldhaheri company used to import and export animals.

Records obtained through the Promotion of Access to Information Act show that in 2022, three South African companies – the Akwaaba Predator Park, Parrot Pet Ranching and African grey parrot exporter Russelle Wheatly – exported animals and birds to Kangaroo Animals Trading.

Akwaaba Predator Park, owned by the South African Nazeer Cajee, exported five cheetahs, five leopards and 14 Bengal tigers to Kangaroo Animals Trading. In his personal capacity, Cajee also exported two white tigers and three “snow” tigers to Kangaroo Animals Trading.

Akwaaba has since been closed, but has been accused of running a lion breeding and canned lion hunting operation.

It underscored a grim truth: while South Africa has no officially registered tiger breeding facilities, it has become the world’s largest exporter of live tigers and their parts, according to the US-based non-profit Big Cat Rescue.

“These animals are bred in captivity for everything from trophy hunting to illegal bone trade, feeding demand in China and other markets,” it said.

Nonetheless, this year, the Wildlife Animal Protection Forum South Africa, an animal rights organisation, published a report claiming that Vantara imported 40 cheetahs from Akwaaba, along with almost 500 other animals. But disturbingly, they could find no record of the South Africa export, except for 40 tigers and one ocelot.

The forum expressed concern about Vantara buying big cats from South Africa to become “breeding machines, exploited within the numerous animal breeding facilities (nurseries) located outside the main zoo” at Vantara.

New evidence suggests that at least five of the Akwaaba cheetahs, seven leopards and 24 tigers went to Vantara via the Kangaroo Animal Shelter. These were not distressed animals in need of rescue, but appeared to be commercial trades.

While neither Cajee or Aldhaheri responded to requests for comments, Vantara has denied this. It says all animals “received from facilities abroad are on a non-commercial basis, with prior confirmation from the CITES [Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species] management and statutory authorities of both countries”.

The UAE CITES Management Authority had not responded to a request for comment by the time of publication.

In an emailed statement, Aldhaheri confirmed that he operated KASC, but denied he was an animal trader.

“The shelter’s sole purpose is the welfare and rescue of animals, and all activities are conducted in strict compliance with UAE laws and relevant international regulations,” he said. “Your claim that I am involved in animal trade is entirely baseless.”

Yet this contradicts what Aldhaheri seems to have written on an animal trading website, where he said: “We are importer and exporter of live animals [sic]”, adding that he is “regularly selling” wildlife, and “regularly buying” exotic animals, including big cats.

This highlights a glaring loophole in the CITES rules. While highly endangered species cannot be traded commercially, they can be exported to other countries provided the shipment is classified as being for a “zoological institution”.

Aldhaheri has not yet responded to additional questions sent to him for this article. Yet he seems to have made changes to his business to make it more acceptable to Vantara.

His company, Kangaroo Animals Trading, has now been converted to the Kangaroo Animals Shelter Center, asserting that its “sole purpose is the welfare and rescue of animals”.

This is what Vantara requires as a registered rescue centre. Indian law says that “no zoo shall acquire, sell or transfer any wild or captive animal except from or to a recognised zoo”.

Exposing Kangaroo traders

Patricia Tricorache has investigated wildlife trafficking for two decades with the Cheetah Conservation Fund and Colorado State University. She has reported extensively on the trafficking of cheetahs out of the Horn of Africa.

“I first heard of Khaled Aldhaheri, operating as Kangaroo Animals Trading, back in August 2022, when a source in the UAE informed me that Kangaroo was using its licence to import and sell lemurs and tigers with CITES permits and selling them ‘under the table’,” she said.

Tricorache said the firm began by trading in livestock, but later moved into more exotic species such as big cats, and Africa’s great apes.

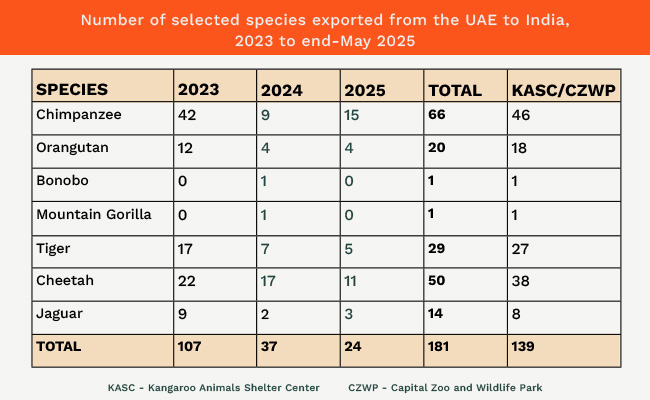

Export records show that KASC and CZWP’s shipments to Vantara included endangered species such as a mountain gorilla, chimpanzees, Tapanuli orangutans, cheetahs, jaguars and Bengal tigers.

Yet all of these species are listed as threatened with extinction, so any trade in them is strictly regulated by CITES, a treaty ratified by both South Africa and India back in the 1970s.

This means trading in those species is only authorised in exceptional circumstances, like for scientific research, and must be accompanied by a CITES-issued import and export permit. Animals seized from the illegal trade may also be exported in exceptional circumstances, such as relocation to a sanctuary, but this is clearly specified as such.

CITES trade records have yet to be made public for 2024 and 2025, so it is impossible to say how many animals were transported without permits. But what is known from trade records is that KASC and CZWP exported 77% of the endangered animals shipped from the UAE to India between 2023 and June this year.

Customs data shows CZWP exported a mountain gorilla to Vantara in 2024, but this seems unlikely to have been one in captivity.

Ian Redmond of the Ape Alliance and the Gorilla Organization, who has worked with gorillas for almost five decades, says “the only mountain gorillas in captivity in recent decades were the orphans in the Senkwekwe Centre at the Virunga National Park” in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“They exist only in the wild in two relatively small areas of forested mountains where the DRC, Uganda and Rwanda converge. If one was exported to the UAE, then re-exported to India, it can only have been taken from the wild,” Redmond said.

And this would have entailed much slaughter. Redmond says the capture would “almost certainly” have resulted in the death of at least two adults – being the gorilla’s parents.

“As most gorilla infants die before reaching competent care, it is very likely other infants would have been captured, also by killing their parents, but didn’t make it,” he said.

Aldhaheri did not respond to a request for comment on the mountain gorilla trade.

Still, there are other red flags in the trade records.

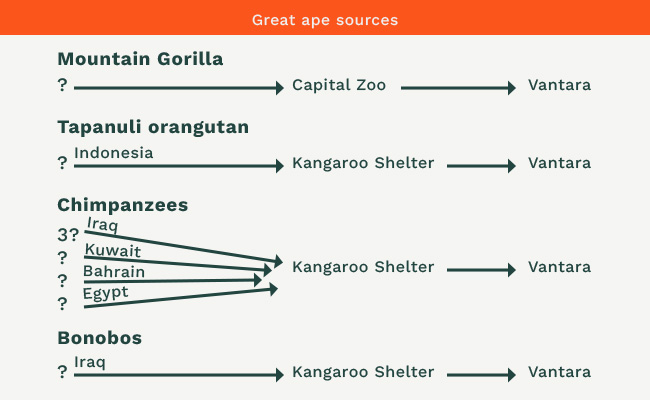

For instance, Vantara imported a bonobo from KASC in February 2024, and there is one CITES record showing that a bonobo was imported to the UAE from Iraq in 2023. Yet Iraq’s CITES data shows no imports of bonobos – a discrepancy often seen as indicating illegal trade.

Among the 25 most threatened primates on earth, found only in the Batang Toru forest in Sumatra, Indonesia, is the Tapanuli orangutan. There are fewer than 800 in the world.

Yet the KASC supplied one to Vantara in February 2024, and the CITES trade database has a record of the UAE importing the animal from Indonesia – but, curiously, Indonesia did not report the export of that orangutan.

Orangutan conservation groups say there is only one way in which such an animal was obtained.

Andrew Gunnyon, speaking on behalf of The Orangutan Project, said: “There are no Tapanuli orangutans in captivity. The orangutan would have been poached from the wild.”

Gunung Gea of the Scorpion Foundation, a wildlife trade monitoring group based in Sumatra, concurs. “I strongly suspect that it was smuggled via eastern seaports of Sumatra crossing Malacca Straits to Malaysia, then to some other countries,” he said.

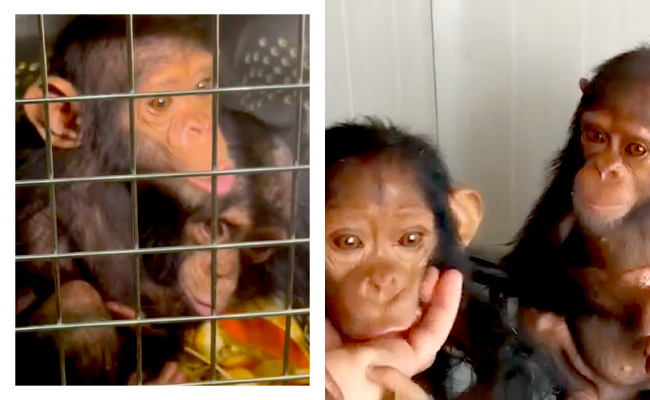

There are similar red flags around the chimpanzees which arrived in India.

While KASC exported 46 chimpanzees to Vantara, CITES reported that only 30 had been imported to the UAE by the end of 2023. None of the chimps arriving at KASC had their origins declared to CITES, barring three that arrived in Iraq from Germany in 2022 and the Tapanuli orangutan from an unknown source in Indonesia.

Indian trade records show that 36 chimps arrived in the country from the UAE in 2023, six fewer than UAE reports having exported. Strangely, India indicates that eight of the chimps originated in South Africa – yet South Africa does not report that export.

However, new questions have emerged after Tricorache shared a video that had circulated on trading groups by an Iraqi dealer, who says he sold seven of the 11 Iraqi chimps to Aldhaheri.

Cheetah shenanigans

There are similar problems with the cheetahs exported to Vantara, some of which came from South Africa. Of the 50 cheetahs that the UAE exported to India between 2023 and May 2025, Aldhaheri exported 38 to Vantara.

Again, this data throws up several contradictions: in 2023, the UAE reported to CITES that it had exported 10 cheetahs to India, all bearing a source code indicating they were from a CITES-registered facility allowed to breed the animals for commercial purposes.

The problem, however, is that there are no such breeding facilities registered with CITES in the UAE. So where did these animals come from?

“Under normal circumstances, cheetahs require very large spaces,” Tricorache says. “In Namibia, for example, the government dictates that the legal space to house cheetahs is one hectare per animal. If the Google Maps measurements are right, [KASC]’s space is roughly 8m x 10m, or 80m2, which would be completely inadequate.”

Aldhaheri’s websites sheds little light on what’s going on.

KASC’s website is a single page with dead links and much of the site’s text is placeholder language in Latin. A Google search of the location lists KASC as a “pet shop”, while satellite images show a small building in the Al Ain industrial area that ostensibly was used to transship thousands of animals to India.

Similarly, CZWP’s website was only created in early 2025, though it is more developed. Some links are active, though most lead to external sites that have nothing to do with the zoo in the Al Ain desert.

Yet some of the animals shown on CZWP’s website include chimpanzees, orangutans, a variety of lemurs and leopards. The website also includes a phone number, which if called plays a pre-recorded message: “Our zoo will remain closed to the public until further notice.”

The website includes numerous positive reviews from supposed visitors, and co-ordinates of its location, which is a barren sandy region to the west of Al Ain. Its structure consists of a long shed with stalls that look more suited to livestock.

Seen together, these revelations about the suppliers to Vantara raises serious questions about the zoo’s true purpose. And much of this would run counter to the message trumpeted by Ambani’s PR machine, which is that Vantara was meant to be a sanctuary for captive animals to live in freedom with the best care.

Yet the media blitz seems to have worked. India’s prime minister Narendra Modi, for instance, has given Vantara his blessing, despite the questions over the real cost to conservation of its methods.

This is despite the fact that numerous sources have cast doubt on how Vantara sources its animals, arguing that many of the purchases amounted to commercial trading in exotic animals, some of it seemingly illegal.

Big Cat Rescue, the US based non-profit organisation, remains deeply sceptical of Vantara.

“While Vantara portrays itself as a sanctuary, its massive acquisitions of animals, particularly big cats, suggest something else. If these animals were truly rescued, where is the evidence of their previous suffering?,” it asks.

Instead, it says, critics fear that “Vantara is stockpiling animals for future breeding programmes – a move that could fuel the exotic animal trade, much like South Africa’s canned lion industry”.

If South Africa is indeed enabling this toxic wildlike trade, it is long past due for Dion George, South Africa’s environmental minister, to intervene.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Having worked in the UAE as the technical director of the Dubai safari park while it was being built and then after completion for a few years, I can state that the number of animal dealers there is mindboggling.

They seem to come out of the woodwork offering all types of animals.

And there seems to be enough wealthy people wanting unusual pets to keep them busy (even though the law about owning exotic animals was put in place to stop it, but seldom enforced )

I had to build a special building to home animals that were rescued or surrendered by people that got tired of their new toy or the animal had grown to big.

In the time I was there I saw everything from big cats to apes and even a Komodo Dragon come through the place.

Often I saw the problem was that the curator or the vet working for wealthy families would bring in the animals while they were young and as soon as they got to big they would replace them just to stay in favour with the family.

I would like to offer any research I can do for you.

Lionexpose

info@lionexpose.org.za