With the finalisation of French group Canal+’s takeover of MultiChoice, the focus naturally moves from “whether” to “what now?”

The most cruel interpretation of the merger would be to cite the famous line: “If you tape two turkeys together, you don’t get an eagle.” Cruel, yes – because as it happens, the merger has a lot going for it.

There is business-model compatibility: both are fundamentally pay-TV broadcasters built on satellite distribution, subscriptions and advertising.

Both are heavily invested in sports rights – MultiChoice through SuperSport and Canal+ through its vast European football packages and African football rights. Both are transitioning into streaming: MultiChoice has Showmax (relaunched with Comcast/NBCUniversal tech); Canal+ has myCanal and stakes in other platforms.

There is a neat geographic and market fit. They are both dominant in Sub-Saharan Africa, but in different parts: MultiChoice, especially in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, and Angola; Canal+ in Francophone Africa.

Both are heavily investing in local content, particularly African soap operas, reality shows and Nollywood. The content strategy of Canal+ remains largely the same and, obviously, there would be significant production efficiencies resulting from a combined entity.

Then there is size. Canal+ currently has about 26.9-million subscribers worldwide, while MultiChoice has about 14.5-million active subscribers. Together, that ranks the group in the top five globally.

All this is good. So where does the turkey idea come from then? It essentially stems from the fact that they are who they are: satellite-based content providers in the era of streaming. This is particularly evident in MultiChoice’s shrinking subscriber base, lower profitability, and tighter margins; ergo, the company’s eagerness to find an exit.

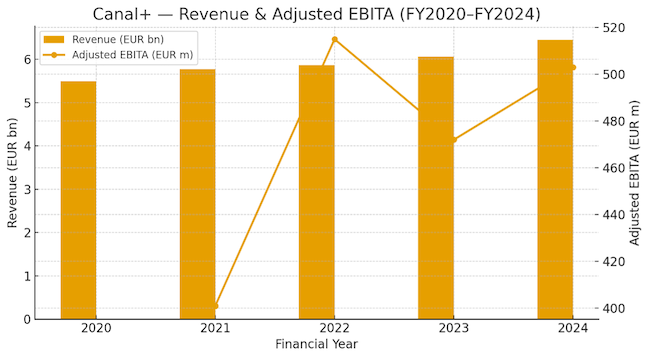

It’s visible in Canal+’s financial numbers, too, which are growing, albeit modestly.

The root of the problem is structural. Both pay small fortunes to maintain their satellite distribution channels, whereas their competitors use an established structure, paid for by someone else, known as the internet.

Satellite services work well in Africa largely because the broadband revolution has not yet fully arrived. This difference is very obvious when you go back to that combined 40-million-plus subscriber base that Canal+ executives like to flaunt: it looks impressive until you place it against Netflix’s 302-million subscribers and Disney+’s 126-million.

The lower prices Netflix and Disney can charge effectively constitute a winning vortex: every new subscriber means that production costs as a proportion of the total subscriber base drop, attracting more subscribers.

Seen this way, the merger is not so much an act of corporate aggression undertaken in anticipation of market expansion, but rather a defensive manoeuvre taken in the face of Genghis Khan looming over the horizon.

But, of course, much can change. Maintaining the satellite distribution could become significantly cheaper, and it probably will. As Africa connects, there is nothing to stop digital subscribers opting for Canal+ over Netflix – and with deep local content, the odds are probably in their favour.

A family empire

There are two further points worth noting regarding the future of the combined group.

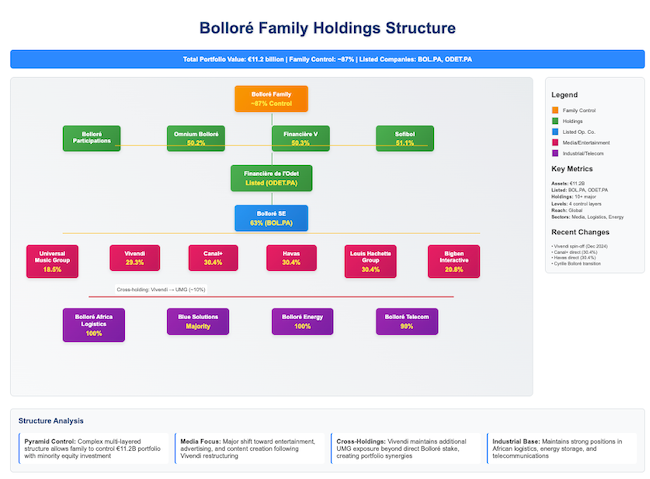

The first is about foreign ownership of broadcast rights. Canal+ is a French media company, wholly owned by Vivendi, which is listed on the Euronext Paris exchange.

Canal+ is not just a French company; it’s regarded as a strategic French media asset, deeply entrenched in the media environment and a fundamental part of French culture, providing news every day.

So how did it manage to take over a South African company which is based in a country where, notionally, there is a bar on more than 20% foreign ownership of media assets?

What the company proposed, and to which most South African and Nigerian regulators seem to have agreed, is that MultiChoice/Canal+ will hold 49% of the economic interest in a separate entity called (originally) LicenceCo, but the combined group will have only 20% of the voting rights. The remainder (51% economic interest and the majority of the voting control) will be held by the BEE group, comprising Phuthuma Nathi, Identity Partners Itai Consortium, Afrifund Consortium, and the Workers’ Trust.

This sits a bit in the grey zone. If only we knew it was so easy to sidestep local ownership requirements? For South African regulators to accept this structure is, in itself, a powerful argument for these backward local ownership requirements to be scrapped.

The other thing is that Canal+, as it happens, also has a deeply embedded control structure. South Africans tapped into the Anglophone world know all about the Murdoch family and its media prowess across the globe. But honestly, Canal+’s controlling shareholder, the Bolloré Group, puts Murdoch’s to shame, at least in the extent and variety of its empire.

The patriarch, Vincent Bolloré, has a history as a corporate raider, perhaps the most prominent in France. In the 1980s and 90s, he pivoted the group from paper into transport and logistics, especially in Africa. His nickname in Paris is apparently “Le Corse” (the Corsican), evoking the other famous French Corsican, Napoleon Bonaparte, even though the family originates in Brittany, which is on the other side of the country.

The difference between the Murdoch and the Bolloré families (apart from the fact that the Murdochs are quite a bit richer, though once you hit $10bn, who’s really counting) is that the handover to the new generation is proving much smoother, perhaps because there is so much more to divide.

Vincent Bolloré has been carefully passing power to his four children, with eldest son Cyrille, CEO of Bolloré Group, overseeing logistics and industry (which is huge, by the way), Yannick, chair of Vivendi, leading the media arm, Sébastien involved in family investments, and Marie engaged in mobility and electric car initiatives.

The point is that South Africans, and Nigerians for that matter, should be aware that their media assets, like so many around the world, are now going to be controlled by yet another single, super-rich dynasty.

What is it about media assets that attracts these powerhouse global titans? Perhaps it’s the power and the influence? Just guessing.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.