Some very significant government announcements slip by without noticeably disturbing the cacophony of South Africa’s political discourse. I suspect, and somewhat hope, that Transnet’s announcement last week that 11 groups have been selected to operate on key rail corridors is one of them.

How significant was this announcement? Both very, and not at all.

Its news is somewhat diminished by the fact that it is part of a longer and more complicated process that has been already announced.

But behind the procedural trail is something much more consequential: South Africa is entering a new era of freight rail transport, underpinned by the philosophy of an overlap between public and private operations. It therefore joins a long list of international rail freight privatisations over the past two decades which – and one doesn’t want to be too depressing about this – have not been very successful.

The risks of going down this route are extremely high, but for the South African government and many others before it, there is a somewhat brutal compelling underlying rationale: they have no option because, as the play title told us long ago, “Asinamali!”

Until the early 2000s, Transnet had been one of South Africa’s “national champions”, underpinning the country’s mining infrastructure. But that has long since gone to pot, not helped by the blur of Gupta-led miasma and wagonloads of money fast-tracking itself up to Dubai.

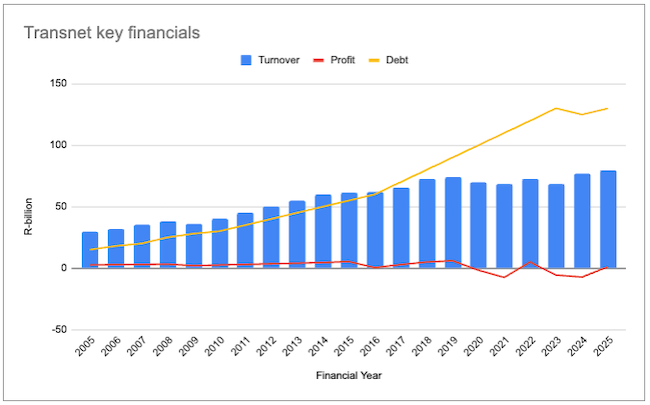

As the graph above shows, between 2005 and 2016, Transnet’s debt more or less tracked its turnover. Then it went bonkers.

Its borrowings hit R130.1bn in FY2023, with R1bn in monthly interest costs and losses of R7.3bn by the 2024 financial year. The company risked insolvency without government bailouts, while capex for infrastructure upgrades wasn’t enough, with only R80bn planned over 10 years against more than R100bn needed.

In other words, a company that once proudly carried its own debt book for generations is now almost totally a function of the taxpayer. Government guarantees started slowly in 2000 with a R15bn underpin but they have now turned into an absolute gusher. Two big ones were granted this year alone, with total guarantees now worth R200bn stretching over five years, all essentially to mitigate credit downgrade risks.

The result is that if Transnet gets this wrong, the burden on the South African taxpayer is going to make the Eskom disaster feel like a walk in the park. And given what has happened in Europe, which has been transitioning through this same process for essentially the same reasons, that chance is not low.

Take the formerly Teutonic paragon Deutsche Bahn (DB).

The previously efficient railway operator now has a reliability rate which makes Transnet look good (actually, it doesn’t – it makes Transnet look less bad). It employs about 300,000 very unionised people, and has a punctuality rate of about 60%. And like Transnet, it is just overwhelmed by debt. In DB’s case, this is about €33bn.

During the early 2000s, the intention was to part-privatise DB, but plans to float a minority IPO were shelved. Instead, DB remained a state-owned “corporation” constantly pressed to act like a private company but without the capital discipline or political freedom to do so. Hello Transnet.

The UK rail privatisation process had different problems for different reasons, but almost nowhere in Europe has a private investment drive resulted in significant gains in transport volumes.

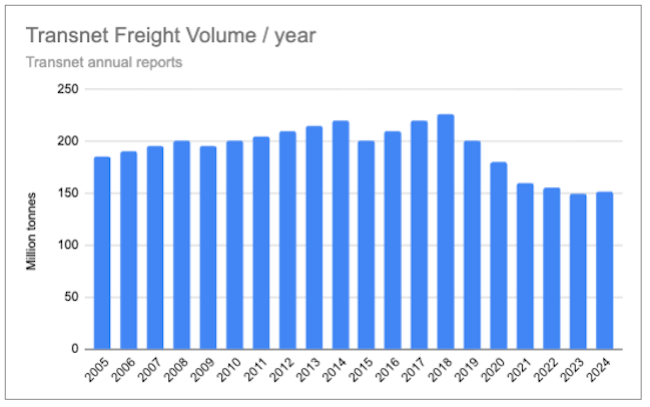

And this is exactly what Transnet, and government, and therefore South African taxpapers, are counting on. Transnet’s announcement on the 11 new freight groups says they are expected to add up to 20Mt of capacity annually starting from FY2026/27, potentially boosting South Africa’s GDP by R100bn-R200bn over the next decade through increased exports and reduced road congestion.

This is critical because freight volumes in South Africa have been declining badly, and are now about 25% down from their high point in 2018.

The ‘open access’ model

But here’s the thing: rather than full privatisation (which would involve selling assets), this is a regulated “open access” model, allowing private operators to run trains on Transnet’s infrastructure for an access fee, while Transnet retains ownership of tracks, signals and maintenance responsibilities.

Hence, there are two absolutely crucial things that have to happen. First, that Transnet charges an access fee that is well balanced; low enough for the new participants to get a return on their investment, but high enough to allow Transnet to maintain the network.

And, second, that Transnet actually does maintain the network. If private players launch their own fleets, it’s not going to help anyone if the copper thieves keep stealing tons of cable and the police look the other way, as you suspect they have been doing. Cable theft has been one of the major reasons why Transnet itself has not been able to maintain its own freight volumes.

The 11 “groups” that Transnet has announced include some international players, which is a positive sign. They also include the logistics sections of some mining companies. And, I suspect, there is some padding with a few wannabes.

Reading the statements suggests developments are still very preliminary, and we haven’t got into the nitty-gritty of the contract negotiations. The actual announcement says that the selected operators still have to “go through the next phase”, when their ability to meet the conditions will be “thoroughly assessed”.

Still, small steps. The train has left the station – or at least may leave the station soon. Or it might not.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.