Aveng, grumbled Rozendal Partners’ founder Paul Whitburn last week, “is the perfect Venn diagram of poor business, poor management and poor balance sheet”.

It’s hard to argue against his downbeat assessment given what has happened to the former blue-chip construction company’s shares over the past 15 years. This year alone, they’ve slid almost 60% as two complex Covid-era projects in Singapore and Australia smashed profits, causing the company to report a R975m loss for the 12 months to July.

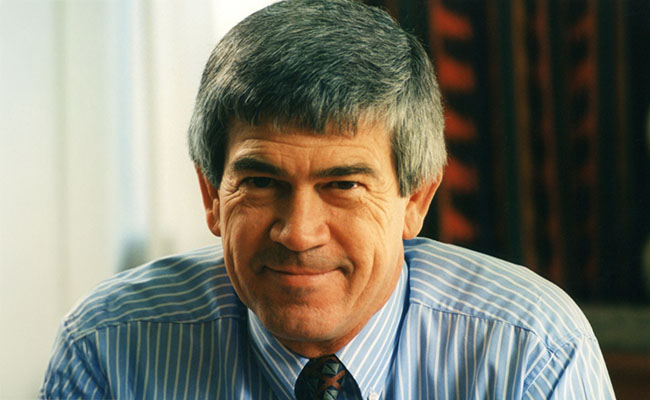

The slump is a major headache for Australian CEO Scott Cummins, who took on the mantle 18 months ago and who is working towards breaking up Aveng into its South African and Australasian businesses. Aveng is on the cusp of selling its last South African asset, Moolmans, but this loss almost certainly nixes the prospect of an Australian listing for its remaining two divisions, McConnell Dowell and Built Environs.

“Transferring a listing on the back of a loss would be difficult to do,” Cummins tells Currency. “So we’re looking at options that might make sense for McConnell Dowell and Built Environs to have a new owner.”

There are fears in the market, though, that the longer this takes, the more value in Aveng will be eroded. It’s a far cry from the optimism that made Aveng a Covid-era penny stock punt, ahead of a 500-1 share consolidation in 2021 that took the share to R28.

Its descent is evident from the fact that on Friday, its stock languished at R5.25 – 81% below where it was four years ago.

It’s another morbid milestone for the South African construction industry, which may soon be left with all of three companies on the JSE: Wilson Bayly Holmes, Raubex and Stefanutti Stocks. Last week, the 120-year-old Murray and Roberts was placed into liquidation.

Aveng, whose history dates back to 1880, is a shadow of its pre-2010 World Cup self. And its R975m loss dwarfs its market capitalisation of just R664m – less than a 10th the valuation it traded at 15 years ago.

But Cummins is confident that within 12 months he will be able to present a plan to the board, revealing that talks to sell contract miner Moolmans are well advanced.

Moolmans, in fact, posted a profit of R1.8m for the year. But on revenue of R3bn, that implies a virtually non-existent margin. And while the group has lately secured a tasty 60-month contract extension for the Gamsberg zinc mine, it has been hobbled by a contract with the Tshipi manganese mine, which is situated in the Northern Cape and is part owned by Australia’s Jupiter Mines and local player Ntsimbintle Holdings.

“The project suffers from a non-collaborative work and operating environment,” Aveng said in its results. “Moolmans has been unable to resolve the restrictive mining claims, together with other claims relating to … power failures and weather.”

Aveng believes it has a claim to that mine, but the owners dispute it. And negotiations have yet to yield any fruit.

“We probably would have had a Moolmans sale deal agreed – at least at high level – if wasn’t for these claims outstanding,” says Cummins.

Asked whether this debacle over the manganese mine could scupper a sale entirely, he says no.

However, “what it might do is change the nature of the deal so there might be a contingent aspect whereby the final sale price is dependent on the outcome of our claims with Tshipi.”

Either way, what is certain is that Moolmans and Aveng are parting ways.

“It just doesn’t make sense to have Moolmans combined with McConnell Dowell and Built Environs,” Cummins says. “There are no synergies. And an investor who wants to invest in contract mining in South Africa and Africa is a different investor [to one] who wants to invest in building infrastructure in Australia and New Zealand and Southeast Asia.”

It didn’t take Cummins long in the job to conclude that there was “greater value” in separating the company than in keeping it together. “Sometimes you have organisations that build up over time, and then you take a fresh look at it and you ask where’s the synergy and what’s the purpose of having this combination of companies,” he says.

Good and bad news

In some ways it’s reassuring to know that the company’s real problem contracts aren’t even in South Africa.

Take “J108” – a 24km railway line extension for the Land Transport Authority in Singapore, which was awarded in March 2020, literally days before the world went into Covid lockdown.

Aveng had put in a tender for a lump-sum agreement on the basis that it would do most of the work on a greenfields basis. In other words, the area wasn’t yet built up with houses or shops or roads – then Covid struck.

While the Singapore government prevented Aveng from working the railway line, the country’s housing development board went ahead with a social housing project in the area around the rail extension.

Cummins says that when Aveng went back to work after Covid, it had lost a year, but the housing development board homes had already been built. When Aveng began to build the viaduct and stations in a built-up city with roads and people living there, it was “a completely different environment”.

Not only did Aveng have to suck up a major escalation in prices after Covid, it had to try and recover costs associated with working in a built-up area.

“We got caught out,” says Cummins. As a result, Aveng has since changed the way it structures these lump-sum contracts.

The bad news is that there is no prospect of making any money back on these legacy projects, of which Aveng still counts 17 on its books.

The good news is that these projects are 94 .5% complete “and nearly all out of the system”, says Cummins, who has set a deadline of 12-months to have all these projects off the books, with the exception of Aveng’s other major albatross, the Kidston hydroelectric scheme in Queensland.

“A lot of them aren’t losing money, they’re just not generating profit. Because a lot of them we did have capped downside,” he says.

But Kidston is in the same cash-draining category as J108; a project that was “too big, over too long a period of time”.

“A pumped hydro scheme hadn’t been done in Australia for 30 years and though we had experts who knew how to do the various parts, being able to estimate the cost associated with a project that goes for five years in a complex environment where you’ve got governments changing and regulations because of union drivers” was tough, he says.

Covid didn’t help, and the last straw was this year’s weather, where floods in the second half of the financial year forced “a full demobilisation” of the site, and a delay of at least 10 weeks.

Nonetheless, Cummins says that if Aveng was ever asked to do it, it would jump at the opportunity. “The intellectual property that we now have, the knowledge, the skills is a real differentiator. But we just need to do it with a contract form that caps our downside and rewards the upside,” he says.

He maintains that McConnell Dowell is still a business that can generate good profits. As of end-June, the division had A$1.9bn in tenders for which it has been designated as the preferred bidder, with a further A$3.3bn in tenders submitted pending a decision.

Built Environs, meanwhile, made A$17m in earnings this year – double 2024’s profits, on revenue of A$491m. It ended the year with “preferred bidder” status of A$106m in new work.

Urquhart Partners’ Richard Cheesman, who buys into special situations on the JSE, is among those who have dipped a toe into the frosty Aveng waters. Calling the numbers “disastrous”, he says Cummins’ value-unlock plans have undoubtedly been complicated by the company’s troubled projects.

However, he calculates that Aveng has built up about R12bn in tax losses “that would be of some value for potential buyers”.

“Outside the problem contracts, operations are holding up, and the balance sheet should be able to bear the associated near-term cash outflows,” he says. “Aveng has been through the wringer, but the next 12 months should show whether there’s light at the end of the tunnel.”

Top image: Aveng CEO Scott Cummins. Picture: supplied.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.