If anything, Enoch Godongwana wanted to make it clear on Wednesday that he was the one who decided to lower the inflation target to 3% – and not South African Reserve Bank (SARB) governor Lesetja Kganyago.

There were no fewer than five references throughout the medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) to the fact that it was the finance minister’s prerogative to adjust the inflation goal – the first such change in a quarter of a century.

Of course, the law is on Godongwana’s side: National Treasury makes the policy, and the SARB implements it. But the minister’s repeated emphasis on his authority stemmed from the SARB’s announcement at the end of July that it “prefers” to aim for the lowest point of the range.

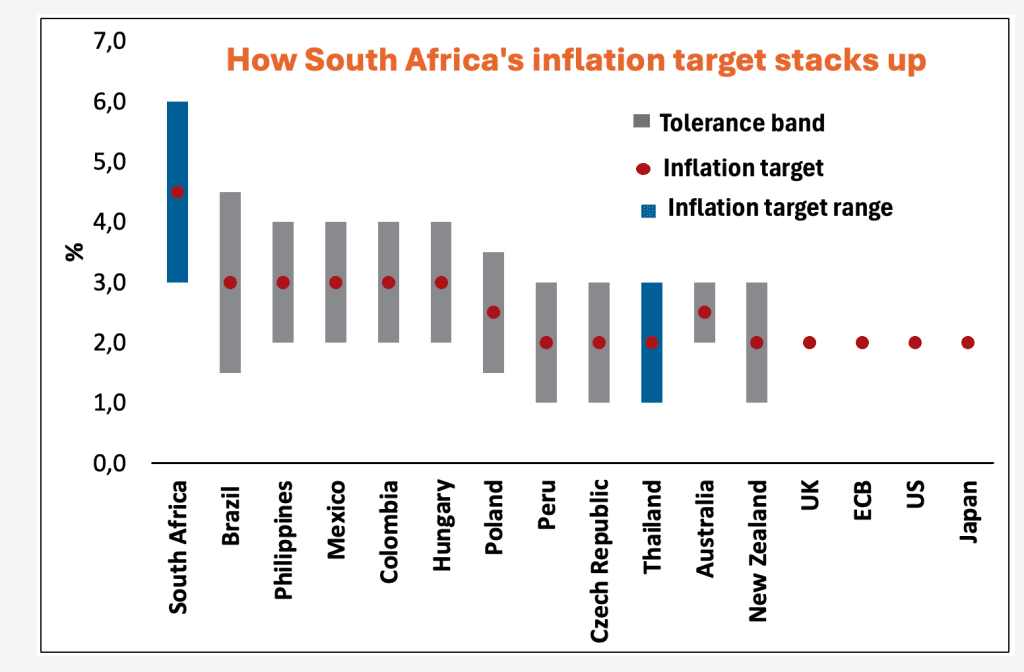

That infuriated Godongwana, who rebuked the central bank’s monetary policy committee (MPC) for jumping the gun. Yet he was backed into a corner – and now, the SARB’s remit has been officially changed, eliminating the 3%-6% range (where it had, in any case, targeted 4.5%). There will be a one-percentage-point “tolerance band” on either side to accommodate normal economic fluctuations.

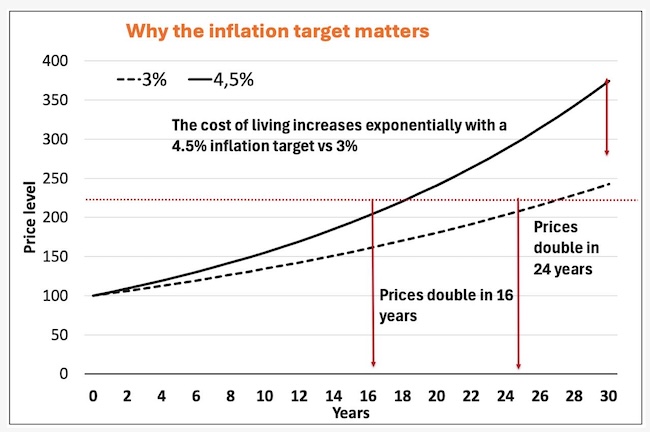

“I have decided after careful consideration to reduce South Africa’s inflation target to 3%,” the minister said in the MTBPS document handed to journalists and economists before his speech on Wednesday. “The new target will anchor inflation at permanently lower levels. This will reduce the cost of living and borrowing costs for households, businesses and government, supporting higher long-term economic growth and job creation.”

The reality is that the government had little choice but to set a new goal. South Africa’s average inflation rate is higher than that of its main trading partners and emerging-market peers, eroding competitiveness and causing a natural depreciation in the rand. Higher inflation also has a far greater impact on the poorest and most vulnerable.

“It’s not my target, it’s the country’s,” Kganyago told reporters during an online briefing from Cape Town ahead of the speech. Asked whether he felt vindicated now that the minister had endorsed the Bank’s position, he replied: “There’s no vindication. There’s only one winner here today – and that’s South Africans.”

Godongwana was adamant that the shift was not something he simply “endorsed”, but that the decision was informed by extensive work done by both the Treasury and the SARB. It was also better “to do it now” than wait for the 2026 budget announcement in February.

That view aligns with what SARB officials have said. Deputy governor Fundi Tshazibana told Currency in August that monetary authorities needed to seize the opportunity while inflation was low and expectations were easing.

Kganyago underscored the importance of price stability, saying: “When inflation walks in the door, public trust jumps out the window. Money becomes worthless.” With household consumption accounting for 60% of GDP, he said a lower target would leave consumers with more money in their pockets, aiding growth.

The one-point tolerance band would give the MPC more flexibility in responding to temporary shocks. “In other words, you do not adjust policy just because you had a sudden surge in food prices or oil prices,” Kganyago explained. “You wait for what we call ‘second-round effects’ – meaning, does that shock lead to other prices in the economy generally rising?”

The SARB can strip out volatile items to assess underlying pressures, he said. Its quarterly models to forecast inflation and set interest-rate paths rely on a single point rather than a range, and because the economy is constantly shifting, figures must be adjusted – including deviations of actual inflation from the target.

“That gap is what feeds into the deliberations in figuring out how monetary policy evolves over time,” Kganyago said.

The trade-offs

Targeting lower inflation will come with short-term costs. Treasury estimates that, initially, lower nominal GDP growth will reduce revenue projections and worsen the debt-to-GDP ratio. But over time, the benefits – higher real growth, improved competitiveness and reduced borrowing costs – outweigh the pain.

The government expects household spending and private investment to rise as real disposable income improves and interest rates decline. The hit to tax revenue should be partly offset by lower debt-service costs, allowing the fiscal balance to continue to improve in the medium term.

In the near term, the lower target could prompt deeper rate cuts than would have occurred under the previous 4.5% midpoint, while anchoring expectations around 3% should eventually make those cuts sustainable.

The Treasury maintains that, with current revenue trends and fiscal measures, the adjustment can be managed without jeopardising fiscal stability. The SARB will guide inflation gradually towards 3% over the next two years, with the minister and governor co-ordinating policy settings to reinforce credibility.

Global inflation is expected to keep easing, though renewed trade disruptions or higher energy prices could reignite pressures. Still, Treasury says risks are balanced and headline inflation “appears to be contained at low single digits – the fruits of consistent, credible monetary policy”.

Inflation expectations, meanwhile, have already drifted from 4.5% towards 3%. Risks remain from geopolitical tensions, rand volatility and high administered prices, while strong agricultural output or a firmer currency would lower food and import costs.

For investors and consumers alike, the move marks a decisive step towards a lower-inflation economy – one that could finally deliver lasting stability.

Top image: Finance minister Enoch Godongwana and Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago. Both pictures: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.