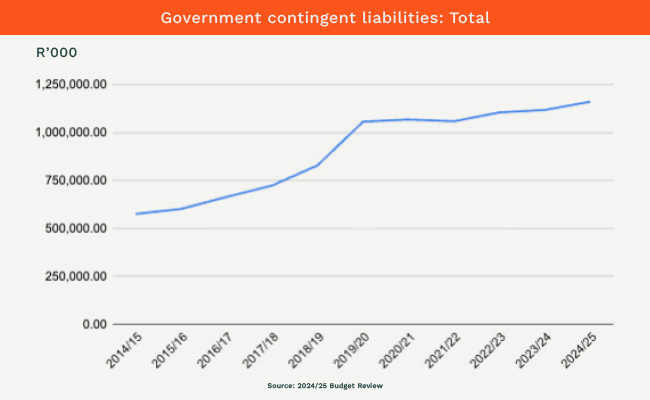

Government’s contingent liabilities have doubled over the past decade, worrying economists and ratings agencies, and suggesting total government debt could be much higher than it appears.

Azar Jammine, director and chief economist of research house Econometrix, pointed out in recent research to clients that the levels of contingent liability could technically add about 10%-15% to South Africa’s national debt, which would mean instead of a 77% debt-to-GDP ratio, the figure would be more like 90%.

“We should be concerned from a long-term point of view,” he said, though he points out this is a complicated topic.

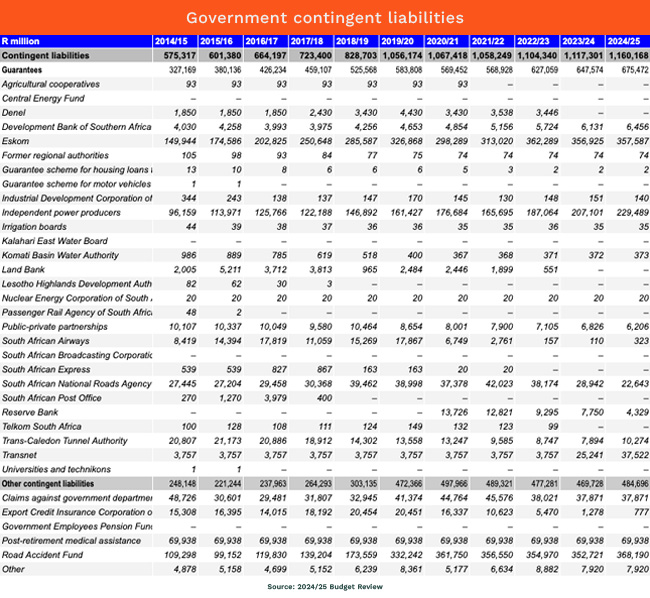

The most recent budget documents show government continent liabilities have increased from R580bn in 2015 to R1.2-trillion today. But to these figures, presented at South Africa’s most recent budget in February, must be added a huge tranche of contingent liabilities of Transnet debt taken over by government in the post-budget period amounting to R145.8bn.

However, government’s contingent liabilities are conditional and uncertain. This is unlike a normal government debt liability, which is generally a direct, unconditional obligation to pay a specific amount at a defined time.

Normal government debt includes bonds, loans or treasury bills, and is recorded on the government’s balance sheet as a fixed liability with a clear repayment schedule, backed by the government’s commitment to pay. A contingent liability, however, is a potential obligation that depends on a future event or condition, which may or may not occur.

The key difference is that contingent liabilities only get added to the actual debt burden if the triggering event occurs. Those triggering events differ according to the specific nature of the contingent liability, and can be anything from very unlikely to absolute certainties.

In a sense, contingent liabilities sit in a kind of financial grey zone, but precisely because they do, the formal requirements to take on contingent liabilities are comparatively lightweight. The new Transnet contingent liabilities, for example, took place without a parliamentary vote, though they do normally form part of the overall budget package, which parliament will ultimately have to approve. In this sense, contingent liabilities could sneak themselves onto South Africa’s overall debt burden, which the government is struggling to contain.

The three big problem areas

Jammine points out that even though the South African government is taking on new contingent liabilities, for the moment at least, they are somewhat covered by the rise in the gold price, which has boosted the value of the country’s gold reserves. But, in the long term, contingent liabilities are a particular problem for South Africa simply because the local economy is not growing fast enough.

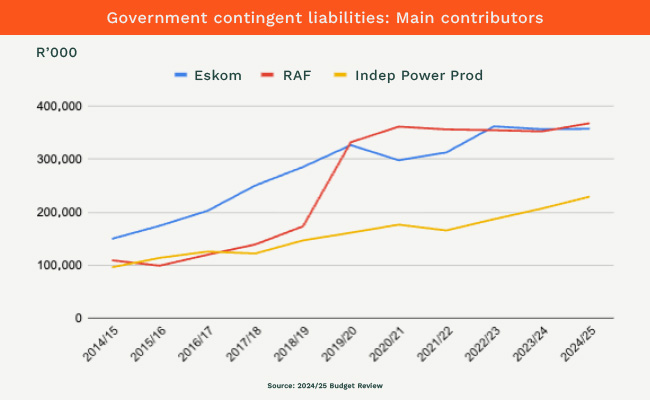

The three big problem areas for the government in this category have been Eskom, the Road Accident Fund (RAF) and liabilities that flow from the independent power producers. Eskom’s debt problems are well known, but it’s noteworthy that the total accumulated by the RAF actually match Eskom’s.

What further complicates contingent liabilities is that some of the debt accumulation is actually welcome if it supports investment and public facilities, and is unlikely to trigger redemption, says Jammine. In this sense, it could be simply a technical addition rather than a real potential liability.

Even though it is large, the contingent liability of independent power producers probably falls into this category, because it will only be triggered if Eskom fails to buy the power produced, which is very unlikely, as Eskom’s debt itself has been covered by government, and Eskom needs the power generation.

From the list below, it is noteworthy how many organisations which had contingent liabilities have dropped off the list, including the SABC, SAA and the Post Office. As soon as these organisations enter business rescue they exit the government balance sheet and the contingent liabilities naturally fall away.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.