How to lose friends and alienate people. It may as well be the calling card of the second Trump administration. And its relationship with South Africa is no exception.

Since taking office, US President Donald Trump has: threatened the territorial integrity of Nato allies; strafed the world with punitive tariffs; threatened the withdrawal of security cover in Europe; suggested strategic allies such as South Korea pay more to host US soldiers in their countries; and violated the territorial sovereignty of another state.

And he’s just one year in. Three to go.

It’s a counterintuitive strategy: Trump’s projection of power has succeeded not in strengthening the US, but hastening its slide as global hegemon. And in doing so, he’s leaving a world in disorder, with China ascendant, Russia apparently resurgent, Europe in flux, and international law relegated to the sidelines.

As Oscar van Heerden, senior research fellow at the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for African Diplomacy and Leadership puts it, US destabilisation of the system has left states scrambling to reconfigure alignment and see how they can salvage multilateralism, co-operation and adherence to international law.

That future, at this stage, remains unclear. “Even though people are not sure what we are going to, they are very sure that we are heading somewhere different,” says Steven Gruzd, head of the South African Institute of International Affairs’ African Governance and Diplomacy programme.

In the cross hairs

South Africa has already felt the sting of the mercurial Trump. False claims of a “white genocide” and pushback against domestic policies such as BEE have seen the country hit with 30% tariffs – the highest in Africa. And continued duty-free benefits on a defined set of products under the US’s Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) – significant for South Africa’s automotive and agricultural sectors – have been extended for only one year, so that’s no slam dunk. And in any event, Trump’s recent threat to slap 25% tariffs on countries “doing business” with Iran could undercut benefits under the Agoa extension, law firm Bowmans has argued.

How immutable these are, given Trump’s transactional policy, is uncertain. On the “white genocide” claim, for example, both Gruzd and Van Heerden see it more as a deliberate, parallel response to South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice than a belief in its own right. And Trump has been known to make and unmake tariffs on a whim, announcing sweeping policy changes on his Truth Social media platform.

Not doing South Africa any favours in US eyes would be its position on Israel. As the Platform for African Democrats’ Ray Hartley and Greg Mills have pointed out in Currency, the expulsion of Israel’s chargé d’affairs late last month was escalatory, when finding a way to negotiate would have been a wiser move.

They also criticise South Africa’s hypocrisy in ignoring anti-democratic African transgressions in multilateral forums, and its silence on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Not everyone agrees. Van Heerden, for example, applauds the non-aligned approach South Africa has taken on Ukraine. And when it comes to the US, at least, both he and Wits honorary professor of international relations John Stremlau believe South Africa has so far taken a principled approach. It’s looking to cement relations while not allowing itself to be dictated to.

“South Africa appears to me to be smartly playing the long game and sticking to its principles, including the rule of law and respect for electoral process – neither of which is in the Trump ‘playbook’,” says Stremlau.

Also not in the Trump playbook is a move away from reliance on the US. On this count, South Africa has looked to diversify markets outside of America. As Van Heerden points out, such attempts are paying off, with trade deals recently signed with Indonesia, and key agricultural importers Malaysia and Vietnam, and a climate and trade agreement with the EU. And, of course, there’s a deal with China in the offing to allow for duty-free access on particular goods (it’s expected to be wrapped up by the end of next month).

On the cards

There are things that can be improved on. South Africa should, for example, be focusing on increased multilateralism and co-operation “rather than the arbitrariness of power politics”, says Stremlau. It’s “the hard work of diplomacy, but it’s the only way to buy consensus to move forward collectively”.

The country could, in that sense, take a page out of Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s book and focus on greater co-operation with other middle powers in the face of a volatile and unpredictable US. It is, after all, a middle power that “exemplifies the promise of Africa”, Stremlau notes.

But Gruzd is on the sceptical side: “Given [middle powers’] diversity of geographic spread, their different kinds of political and economic systems, it’s not going to be easy to see them come together.”

So any reform of the system – if it happens at all – will be a long road.

At the same time, South Africa could leverage its relationship with the rest of Africa – currently a blind spot.

Economically, it’s a huge market to be tapped, with “lucrative and important markets right across the continent”, says Gruzd. For starters, Africa has a combined population of 1.4-billion and GDP of $3.4-trillion. And right now, only about 15% of African trade is intracontinental, he adds. By putting more effort into the African Continental Free Trade Area, South Africa could further boost diversification of its economy and markets.

It could also put its critical minerals to better use. Mining analyst Gracelin Baskaran recently argued in Business Day that South Africa should leverage its rare earth supplies in the face of waning Chinese dominance of that particular market. It’s a step that will demand more co-ordination than currently exists: Baskaran says it requires a strategy that brings together mining, trade, foreign affairs and finance functions. This would be a rare moment of true co-operative governance in the country.

G20: the elephant in the room

Diplomatically, South Africa has some things going for it. It has, for example, punched above its weight at the G20, proving to be an active and positive force, says Gruzd. And the Joburg event was a “tour de force” even without the Americans present, says Stremlau.

Of course, Trump has excluded South Africa from the 2026 affair. It’s a diplomatic blow, but not terminal – it’s simply South Africa “taking a gap year”, says Gruzd, and focusing its attentions on next year’s event in the UK.

In any event, this year’s G20 is likely to be pared down, with items like climate, inequality, diversity, poverty, hunger and other issues South Africa put on the agenda falling away. Still, Van Heerden doesn’t see that undermining the co-operation that was agreed on in South Africa; the department of international relations and co-operation will continue to take forwards the relationships forged there, and will pick up with the G20 again next year.

Choosing friends

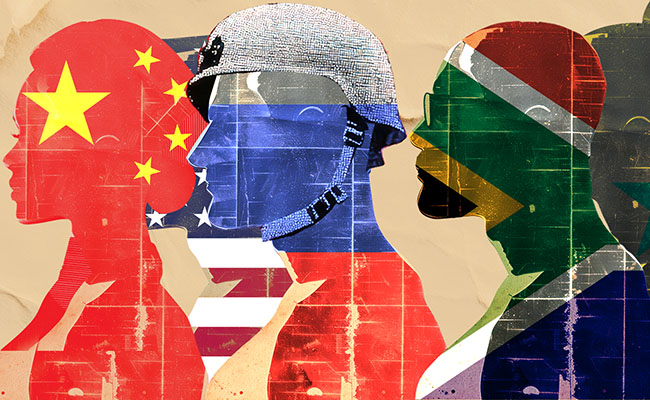

A potential sticking point – thrown into sharp relief by recent “war games” with China, Russia and Iran – is South Africa’s relations with so-called rogue countries and whether these undermine its relations with its European partners.

Hartley and Mills believe “South Africa’s strange foreign policy pivot” towards autocratic states indeed risks harming the country’s international standing.

Others are more sanguine. While this is unlikely to do the country favours in the longer term, they say, there’s an element of pragmatism in this. Beyond competing ideological narratives around the military exercises, Van Heerden, for example, points to Europe’s recognition of South African sovereignty in its actions.

And as Gruzd puts it, Europe has been “less vocal about who South Africa’s friends are than the US has”, while Trump’s tariffs on Europe have perhaps allowed the continent and South Africa to find greater common cause.

But the country “can’t have it both ways indefinitely”, says Stremlau. While he accepts that South Africa is seeking economic assistance wherever it can get it, it will at some point need to make a change to its affiliations. On this count, he reckons a move towards the G20 rather than the Brics would be most advantageous – a move, in other words, away from a bloc that’s dominated by autocratic states to one with a preponderance of democracies.

Still, that’s no easy ask, given the ANC’s ambivalence towards the West, and the ties it forged with other countries during apartheid, he adds.

Headed for ‘lame duck’ status?

As for the US, much remains uncertain. Trump may become a “lame duck” president by November, when mid-term elections in the US could see the Democrats flip both the Senate and House of Representatives, says Stremlau (though the House may be the easier of the two to turn). That would hamstring Trump’s sweeping domestic and international agendas, as Congress exercises a more stubborn check on his executive power.

But all this makes him no less dangerous in the short term. Particularly if he decides to shore up support by projecting power internationally where he’s losing the public domestically.

Within this malaise, South Africa would do well to recognise its limitations: it remains a relatively small power – it is a minnow swimming with “whales and sharks”, says Gruzd.

ALSO READ:

- Claiming the ground beneath the elephants: Africa’s new geopolitical challenge

- China’s African harvest: Trade wars are reshaping the fruit bowl

- Now the party is over, who washes the G20 dishes?

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.