Last month people around the world gathered under the night sky to observe the total lunar eclipse, known unsettlingly as a “blood moon” due the rusty tinge the moon takes on as sunlight refracts through the earth’s atmosphere. Much of the discussion around our little campfire that night, and perhaps yours too, was about what in the heavens our ancestors thought when they watched this celestial spectacle. Given how much of what we see depends on what we think, the question could also be asked another way, which is: “What did they see?”

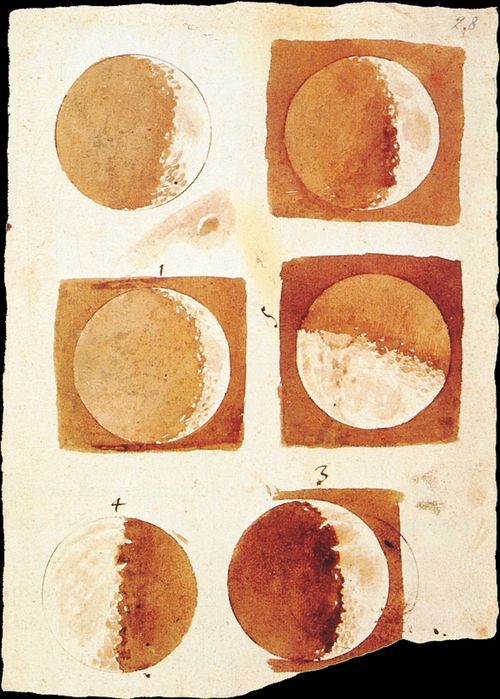

There’s a wonderful drawing that illuminates this principle nicely. Galileo is often credited with giving us the first recorded image of the moon’s surface in 1609. This ink drawing of different phases of the moon is mesmerising: six globular moons moving luminously in and out of shadow on a single page. The orbs are described simply in washes of brown ink and some are suspended in bulging squares of night.

It’s a thrilling moment, the human eye seeing through a telescope for the first time the landscape of the moon. Yet what really makes Galileo’s moons historically momentous is something seemingly irrelevant – the way he’s painted that irregular hemispheric border between the moon’s day and night, and the subtle brushstrokes that appear on the moon as it shifts out of the earth’s shadow into the sun’s light.

Looking at this image today, we recognise instantly that those irregular markings represent the moon’s mountainous and valleyed terrain. But this wasn’t always the case. These dimpled ink moons were the first tremors of Galileo’s troubles with the Church.

The moon you see, was a heavenly sphere: it was supposed to be uncorrupted, perfectly smooth, immaculate. Those dark smudges that are visible from earth even with the naked eye – the rabbit or the man in the moon, depending on your inclination – were explained away by physicists and priests alike as changes in the moon’s density, not changes in its uniform shell. According to holy edict the surface of the moon, like that of all other celestial bodies, was a divinely polished marble.

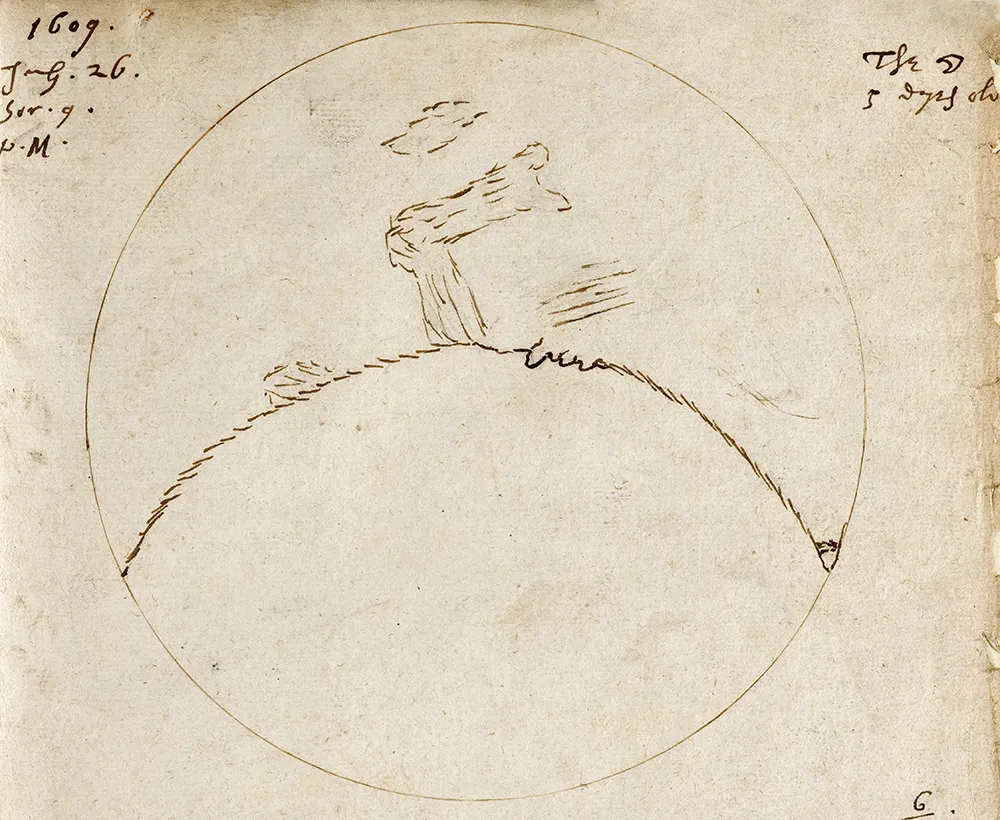

It turns out Galileo was not the first person to look at this heavenly sphere through a telescope, or even the first person to make a drawing of what he saw. Four months earlier, the English polymath Thomas Harriot had done just that. But Harriot’s drawing of the moon is spectacularly underwhelming. A simple line drawing, it reflects none of the weight and awe of Galileo’s. Rather than being descriptive or clarifying, Harriot’s obscure scratchings seem to reflect the incomprehension of their author.

Why, asks the art teacher smugly, is there such a dramatic difference between these two depictions? Galileo, alongside his pursuits in mathematics and physics, also studied at the Academy of Drawing in Florence, receiving instruction in perspective and, crucially, chiaroscuro.

In art, chiaroscuro (Italian for “light-dark”) refers to the use of tone and contrast to create volume in drawing and painting. While Harriot sat in cold grey England and looked up at a marble, Galileo was surrounded by painters such as Caravaggio, who were mastering the use of chiaroscuro to model depth and space. Which is to say that when Galileo looked at the moon, he understood that the irregular patterns of light and dark he was seeing indicated three-dimensional mountains and craters casting shadows. He was able to see what he was seeing.

Although Harriot’s initial drawing makes an attempt to describe that rugged surface, we know from his correspondence (which mentions the “strange spottednesse” of the moon) that it was only after he saw the engravings of Galileo’s drawings, which were published with his writings, that Harriot understood what he was seeing. Having finally seen what he was seeing, he then went on to produce some more impressive (and face-saving) maps of the lunar surface.

The invention of the telescope that ostensibly allowed both these men to see the surface of the moon is one important piece of technology in this story; the other, of course, is chiaroscuro. It also seems likely that it was Galileo’s artistic training that gave him an understanding of the mechanics of reflected light and allowed him to observe what’s known as “earthshine” – a glow that appears within the dark shadow of the moon, as a result of light reflected off the Earth. In his moon drawings, the gradations of his inky washes are the proof.

A universe in conflict

The cratered moon was not the only thing Galileo saw through his telescope. He saw moons orbiting Jupiter, he saw sunspots shift across the sun, he saw Venus cycle through phases just like the moon. All of which supported the idea of a sun-centred solar system. And none of which pleased the Church.

The powers that be insisted on Earth being the fixed centre of the universe and hauled Galileo before the courts for heresy, banned his books, put him under house arrest – and under threat of torture forced him to recant. The irresistible and apocryphal story is that Galileo, who by all accounts was both rebellious and pragmatic, is said to have muttered under his breath as he left the courtroom, “Eppur si muove…”; “And yet it moves…”, indicating (quietly) the irrevocability of what he had seen with his very own eyes.

Well, that lil’ legend always gets me weak at the knees. My mother unfairly claims the reason Galileo is my history crush is because he resonates with the passive aggressive in me. She may be right, but something else I share with Galileo is a love of both science and art – both disciplines of observation and meaning-making, both rational and intuitive in their own ways.

Unfortunately, since the inception and rise of science, art’s been rather downgraded. And these days certain actors are making a concerted effort to undermine science too. Galileo’s moons are an eternal reminder to hold on to both. To celebrate and protect all the technologies that help us interpret the world.

Next month, the full moon will be at its perigee, the closest point in its elliptical orbit to Earth. It will be the second of three consecutive “super moons” and it’ll appear larger and brighter. By all means, charge your crystals, set your intentions, serenade or howl, but also take a moment as she crests the horizon to cast your eyes over her textured blemishes and wonder at the knowledge we have, and don’t yet have, of her glowing landscape.

Sarah’s note: If this piece gripped your brain and eyes as it did mine, know that there’s more where that came from. Rebecca’s next online course, titled Feast For the Eyes, starts on 5 November and runs to 26 November, weekly. It will consider the intersection of food and art through the ages, and sample the delights of both art history and cookbook illustration. Delicious! It’s R1400 and booking details are here.

Top image: supplied

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Rebecca is a drawing teacher of such exceptional talent; she has skill, tenderness, knows and shares the history, has humour and teaches us not to be judgy. The only thing I ❤️ more than her online classes are her in person workshops.

As a physicist and art lover, I was truly intrigued by the historically well-supported description, enriched with a subtle touch of contemporary critique addressing the recent backlash against both science and art.