You wouldn’t think that the most popular show at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC this year would be an exhibition of early 20th-century floral watercolours. But like all good viewing experiences, where we begin will not be where we end up. The exhibition Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers is ostensibly a series of nature studies done between 1919 and 1920 by the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint.

I was intrigued because af Klint is much more famous for her series of large abstract works, created under instruction from the voices of spirits contacted via séance. These pieces are colourful and strange, and radical, if you consider that pure abstraction in art hadn’t really hit the shelves yet and her contemporaries would have been painting wholesome Swedish peasants and dim interiors.

But that’s a story for another time; in 1917 af Klint abandoned the abstracts and turned her attention earthward. And so it is that 46 sheets of her beautiful botanicals now line the walls of a sage-green room at MoMA, creating the feeling of a lush meadow.

Hilma af Klint. Convallaria majalis (Lily of the Valley), Geum rivale (Water Avens), Polygala

vulgaris (Common Milkwort). Sheet 11 from the portfolio Nature Studies. MoMA

In one the colour of a slender stem undulates from emerald green to ruby red at the nodes; look between the leaves and two tiny, jet-black ants wave their feelers about. Each sheet offers immaculately observed plants in delicate and glowing watercolours – flowering boughs and budding branches, sinewy roots and burnished fruits, all complete with their vernacular and Latin names in a neat cursive script.

This is no ordinary florilegium though: floating about the pages next to each plant are tiny enigmatic diagrams, small squares and circles divided into coloured geometrics or filled with spirals and dots, like the unhinged key of a map. Ah, here’s the af Klint we know! This is where af Klint the scientific illustrator meets af Klint the visionary mystic. The author of these drawings was hoping to observe more than reproductive cycles and habitats, she was searching for nothing less than each plant’s soul.

Those little graph-like diagrams, called a “riktlinier” (guideline) by af Klint, are occult visualisations and correspond to notes in which she attempts to pin down the spiritual character of each plant. In some of these notes you can make the astral leap with her: the juicy European gooseberry for example manifests “longing to conceal selfish wellbeing.”

Others are more obscure: the hawthorn has “ignorance regarding refinement of form”, and more alarmingly, “hostility toward the reproduction of animals and humans”. The European white birch, whose drooping bough hangs over a riktlinier in the form of two intersecting multicoloured crosses, has “sensitive thoughts”.

Hilma af Klint. Prunus padus (European Bird Cherry), Prunus avium (Sweet Cherry), Prunus cerasus (Sour Cherry), Prunus domestica (European Plum). Sheet 7 from the portfolio Nature Studies. MoMA

The arcs and lines of each small riktlinier seem to pin their subjects down; each innocent botanical is laid bare – they have a zest for life, a lust for power, they are complacent, humble, or grouchily resilient. I was left with the uneasy impression that the plant spirits, like their human counterparts, manifested a good deal of longing, a fair amount of hostility, and a sprinkling of goodwill.

The idea that the natural world is animate is nothing new, the botanist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks of the American Indigenous tradition of taking advice from the birch people or bear people or rock people. But nature’s animacy is an idea that is increasingly gaining currency in the contemporary Western world. The nature writer Robert McFarlane’s new book asks Is a River Alive? Across the globe advocacy to grant nature legal personhood is gaining traction, closest to home with the recently launched Table Mountain campaign.

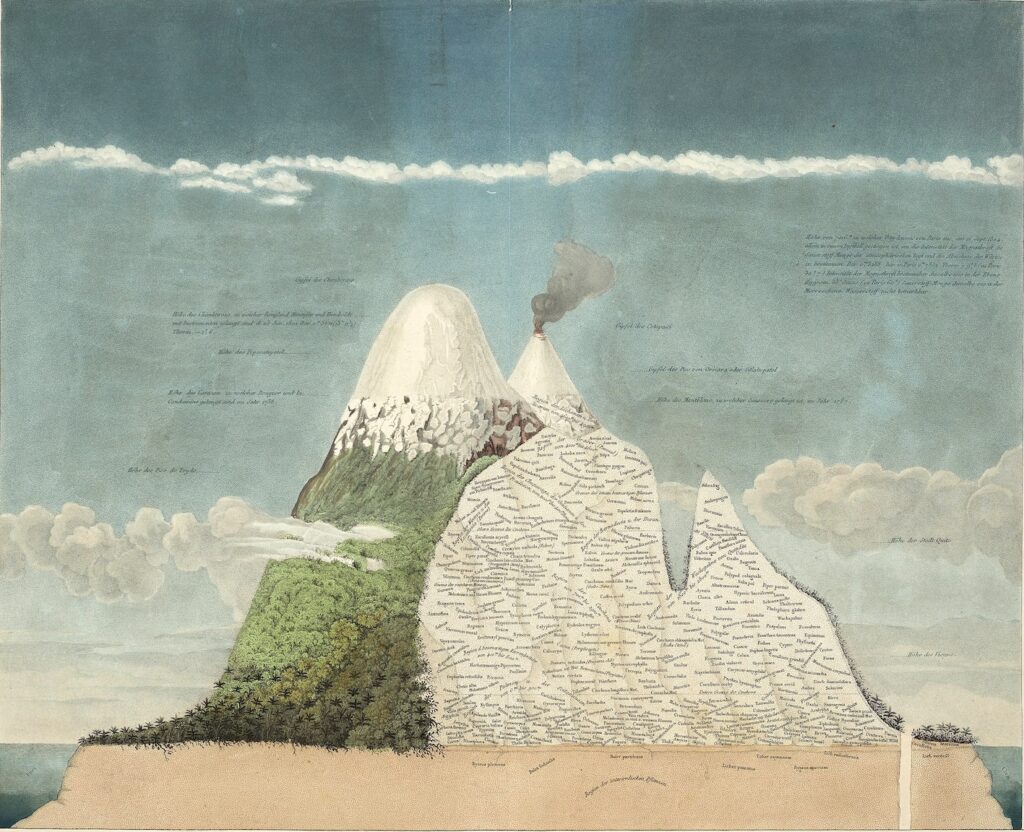

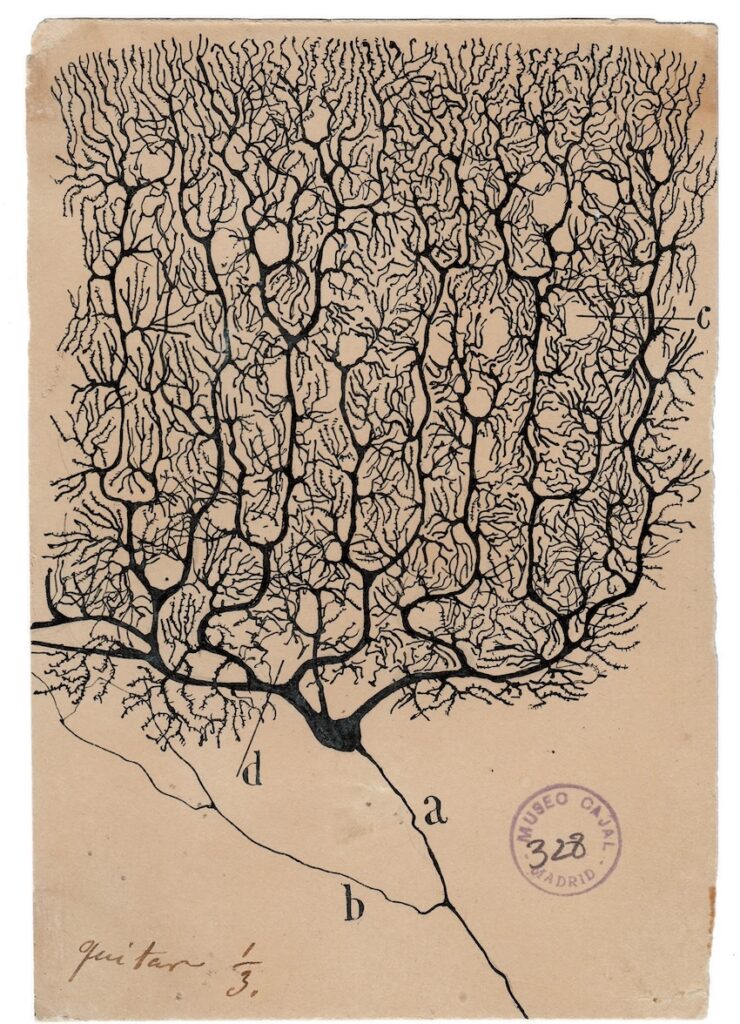

The use of drawing as a tool of observation and study is also not novel. The brilliant naturalist and polymath Alexander Humboldt drew voraciously as a way of figuring out the systems he was looking at (in 1800 Humboldt was the first person to identify human-induced climate change) and the neurobiologist Santiago Ramón y Cajal insisted on sketching in real time what he was seeing through the microscope, as he said it was the act of drawing that enabled him to see what he was seeing (his innovative theories on neural functioning were only confirmed 12 years after his death when technology improved). In the end it’s not such a stretch to think that there are “invisible” sights just waiting for the right eye to come along.

Alexander von Humboldt, Tableau Physique, 1807, Public Domain

Ramon y Cajal, Purkinje neurons from the human cerebellum, 1899, Cajal Institute, Madrid.

What’s enticing about af Klint’s intricate watercolours and their atomic diagrams is her dedication of vision: the earnest and ardent attempt by the artist to really consider her subject, from its roots to its aspirations. Each illustration is suffused with an awe which will wear down the hardest heart.

I began to find her intensely focused little abstractions on each page peculiarly convincing. Nested squares, precise divisions filled with jaunty colours, effervescent spirals and gilded triangles, radiating dots; as I looked these geometrics merged with gnarled roots, tiny stamens, the shadows of leaves, ungenerous petals, power-hungry stems, obedient fruits, flowers full of longing – I was happy to drink the Kool-Aid.

I was reminded of something I did during a pandemic lockdown: I spent three days drawing a vase of roses picked from my garden, as they slowly collapsed and dissembled on my kitchen table. And let me tell you, I saw things. The soft white roses were not quiet and fey at all. Over three days I watched an opera unfold. There was drama! Hostility! Longing!

As humans we are primarily visual creatures and when we allow our eyes to lead us, we should be prepared for a journey. These balmy botanicals reminded me to be wildly curious. Where indeed might we end up, if we spent long enough looking – really looking – at the blossoms and daisies and green shoots that are about to burst forth as spring arrives?

‘Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers’ is on at MoMA, NYC, until 27 September 2025

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Thank you …. this is special. Love Hilma af Klint and your reference to Cajal drawing in order to “see what he was really seeing”. Looking beyond the obvious.

Beautiful Rebecca

I love this writing Rebecca. Your description of your experience of drawing the vase of roses during lockdown was an illuminating culmination! – I suddenly felt I know the drama! hostility! longing! of a vase of flowers transforming before my eyes.