Mark Kretzschmar, the 56-year-old broker who allegedly swindled more than R40m from friends and family over more than a decade, is languishing in Joburg’s notorious Sun City jail, with no date having been set yet for a bail hearing. Two weeks ago, Kretzschmar was arrested, and appeared in the Alexandra magistrate’s court on charges of theft of R2.8m, but any hope of being released on bail vanished when prosecutors revealed a multitude of other cases had been lodged against him in other cities.

Mannie Witz, the advocate who represented Kretzschmar in court, said this week that no bail hearing could be held until all the complaints had been consolidated.

“There were complaints lodged all over the country, including from Bedfordview, Bramley and Vaalwater, and so those cases need to be consolidated by the National Prosecuting Authority. We expect that to happen in the next few weeks,” he told Currency.

Witz said Kretzschmar has in recent days been visited at the jail, south of the city, by his lawyers, who also arranged his medication. “So far, he is coping,” he said.

But in the absence of Kretzschmar offering any explanation, as he would in a bail hearing, this leaves a shroud of mystery hanging over what would seem to be one of the more high-profile scams of recent years.

For answers, eyes have turned to the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA), the regulatory watchdog for the investment sector. In June, the FSCA warned investors against dealing with Kretzschmar, and said it would launch an “investigation” into what happened.

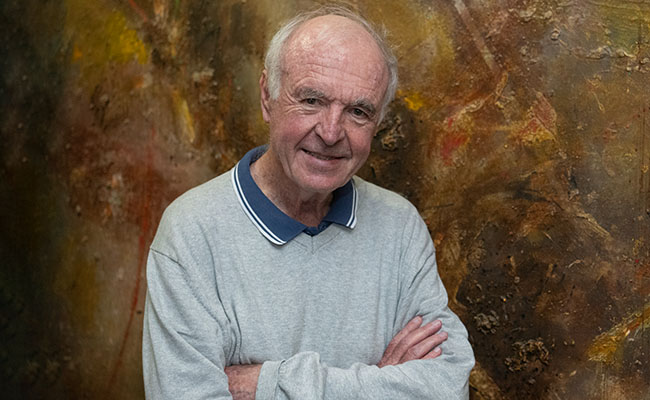

Gerhard van Deventer, the FSCA’s head of enforcement, tells Currency that “we have completed our preliminary investigation” and from the probe, “it doesn’t appear as if the funds were invested in a financial product”.

This will be chilling news for those investors who were still hoping the money they entrusted to Kretzschmar had been invested in “safe, solid stocks”, as he promised, and could be recovered. Van Deventer says Kretzschmar has now been debarred by the regulator – effectively blocked from acting as a financial adviser – and “we will now consider how the case will be dealt with”.

Nonetheless, questions continue to swirl around a company called Freedom Capital, based in Illovo in Joburg, which has been linked to Kretzschmar. Some of the investors took comfort from the fact that he appeared to be operating under Freedom Capital’s financial services licence.

The FSCA says it had “engaged with Freedom Capital”, and the regulator believes that Kretzschmar used the company’s financial services provider number “without [its] permission or knowledge”. Van Deventer says that once Freedom Capital found out what was happening, it “reported the matter” to the regulator.

But investors who spoke to Currency remain sceptical, and the FSCA itself seems not to have closed the book conclusively either, saying it will “consider the matter further”. Messages from Currency to Freedom Capital and its senior officials went unanswered this week.

Police have calculated that more than R40m has gone missing based on the number of criminal complaints, but some victims feel the real number may turn out to be closer to R200m.

“Many families, including many well-to-do families, have lost a lot of money, but some of them seem reluctant to raise their heads at this stage,” says Anton Maybery, the son-in-law of one of the victims, 86-year-old Sally Coulter, from whom Kretzschmar took R6.2m over 16 years. She had first met Kretzschmar years ago, since she was friends with his wife’s family.

Maybery says some investors are resigned to having lost their money, and are now watching to see whether Kretzschmar gets an extended jail term.

“It seems, at this point, that there might be nothing left. Mark led an extravagant lifestyle. But everyone thought he was running a successful asset management business, doing well for his clients and therefore himself. No-one ever doubted his credentials, so there’s a fair amount of shock involved,” he said.

He says the exposure of “the real Mark” had been like a horror movie. “It’s unthinkable that this likeable, upstanding, generous, great father, could have been perpetrating a sophisticated fraud and theft scam that appears to have started back in 2009 and ended in February.”

In February, the wheels first came off when Kretzschmar vanished, leaving his friends “to believe he’d been kidnapped”, Maybery says. While he then resurfaced, the cracks in his investment scheme widened, before finally busting apart in May.

‘Happening for centuries’

Drawing lessons from this case is difficult, since the obvious red flags were not present. For instance, investors were not promised the sort of sky-high returns you see in a Ponzi scheme and, when asked, Kretzschmar pointed to Freedom Capital’s registration at the FSCA as evidence of his legitimacy.

Van Deventer concedes that this made it more difficult for the victims to spot. “It seemed as if it was business conducted lawfully. It is difficult for the public to mitigate risk under these circumstances [and he] used the details of a legitimate financial service provider to provide credence to his scheme,” he says.

Matt Matthee, a financial planner at Graviton Wealth Management, says that aside from the very obvious cases – where the returns are fantastical, or there is no obvious model – it is often difficult for an investor to spot a con.

“We see it the whole time in the industry. The story of people being scammed, particularly old people, has been happening for centuries,” he tells Currency. “It’s often tricky to detect it, but there are a few telltale signs, like if someone is promising you a guaranteed return of, say, 13% per year. Nothing increases in a flat line like that, unless it’s cash.”

Verifying the identities of the advisers with the FSCA is one protection, as is researching the track record of that adviser – but it’s no failsafe. “In the end, you can do everything, and it’ll still happen. You do your best to avoid it, but you’ll always have greedy people looking to exploit others,” he says.

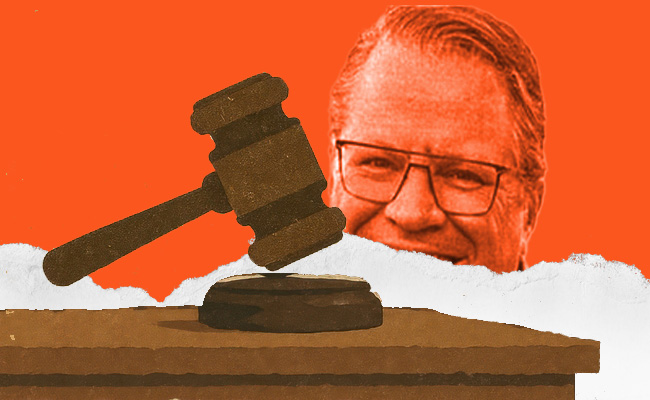

Top image: Mark Kretzschmar. Missing poster; Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

My mom got taken by this character. She was elderly and linked to him via family. She had previously had a tiny amount of money invested with him so trusted him. The money she then invested was to care for my sister. The FSCA- a little late to the party, I am afraid. How have they helped the investors? I am hoping they do a thorough investigation