In ‘Overlanding Through the Boardroom’, Johan de Villiers turns bush lessons into business ones. In this edited excerpt from the book’s third chapter, he traces how a night drive through Malawi’s mud became a parable about overconfidence – and why the same bias that traps travellers also derails projects, cash flow and corporate strategy.

In April 2021, Kim and I travelled to Lake Malawi to complete a bucket list item and do some tropical freshwater diving. The lake is renowned for its secluded beaches and tranquil coves, often described as the quintessential fly-and-flop destination. Beyond its scenic beauty, it is a snorkeller’s paradise. The crystal-clear waters are home to more than 1,000 species of brightly coloured cichlid fish, many of which can’t be found anywhere else on earth.

While researching the trip and where we might stop off along the way, we stumbled upon the Mulanje Mountain Forest Reserve. Covering 56,317ha, this reserve earned its status as a Unesco biosphere reserve in 2000. It stands as one of the few spots in Malawi that remains untouched by deforestation. Towering at more than 3,000m, Mount Mulanje, known locally as the “island in the sky”, is the country’s highest peak, rising dramatically from the plains of Chiradzulu and the tea-rich Mulanje district.

Eager to hike the mountain and explore its rock pools, waterfalls and forests, we discovered a mountain cabin operated by locals that had availability. We decided to begin our journey with a weekend stay in this rustic abode before moving on to Lake Malawi.

According to my online research, the journey from the airport in Blantyre to the village would take us no more than 90 minutes. Most of the route was tarred, although online sources did warn about the occasional pothole. Our flight was scheduled to touch down at 2pm, so I allocated two hours for the drive. This included 30 minutes to pick up our rental car at the airport and perhaps refuel. No problem, I thought – we’d reach the village no later than 5pm.

However, the universe had other plans for us. First, our flight was delayed by half an hour. Then, to our dismay, we learnt that the car rental agency wasn’t at the airport but rather in the heart of Blantyre, a little over 16km away, which meant navigating through the city’s bustling Friday afternoon traffic to reach it. We arrived at the dealership half an hour after leaving the airport. By then, it was just after 3pm.

We weren’t planning on doing any heavy 4x4ing, so we rented a little lime-green Suzuki Jimny, which we aptly nicknamed “Jelly Tot”. Shortly before 4pm, the licences, insurance and paperwork were processed. I pulled up the Tracks4Africa map on my GPS, and off we went. To our dismay, the roads were in terrible shape. To compound matters, being in the sub-tropics, the sun sets at about 5.30pm in Malawi in April, earlier than I’d expected.

By the time we reached Mulanje, darkness had set in without a single light in sight. The tar road transformed into a dirt track, leading us through villages and fields of maize, bananas, sweet potatoes and other crops before we found ourselves in the forest. Before long, a river crossing loomed ahead – a daunting expanse of mud and water stretching about 80m. We weren’t in my Landy – we were in a liquorice-packet-coloured Suzuki Jimny with standard all-terrain tyres. There was no way we were going to get across all that mud. I made several detours, but each one brought us back to the river.

Each time we found ourselves trapped in another forested dead-end, we’d see 10 to 15 pairs of gleaming white eyes watching us. We couldn’t tell if we were a curiosity or a nuisance; in that kind of darkness, uncertainty does the work of fear.

By 7pm, under the pitch darkness of the African night, we were utterly disoriented, yet our GPS stubbornly insisted we tackle the muddy river crossing. As we approached the river once again, I noticed the Jimny was equipped with low-range and traction control. “You know what?” I said to Kim, feeling somewhat more confident, “we’re just going to have to wing it”.

With that, our neon lime-green companion plunged into the mud. We held our breath. She wiggled. Light on her feet, she didn’t sink like a heavier vehicle might have. Instead, she skimmed atop the mud, flinging it everywhere.

Zzzip! Eighty metres of thick mud, and she sailed across it. When we came out the other side, she was caked in mud, but she was like a dog wagging her tail with a ball in her mouth, saying, “See, I told you I could do it!”

I was in awe. The whole experience made me realise just how much I’d underestimated the Jimny. My respect for it grew tenfold.

Some 7km later, we reached our cabin, muddy but triumphant.

As I reflected on our adventure, I was reminded of a BBC documentary I had watched years ago. The programme featured an engineer who played a part in designing the original utility Land Rover back in 1948. Clad in a sharp tweed jacket and tie, he was asked about the most crucial aspect of an overlanding truck.

His response was unambiguous: “Tyres, my son,” he said. “Tyres.”

Tyres are your vehicle’s sole contact with the ground. Regardless of the kind of machine you have – even if it’s the world’s best – its performance hinges on its tyres. Without proper traction, self-cleaning properties or grip, it will simply spin helplessly in place. For me, tyres are everything. Never cut corners on them. Always invest in the best you can afford, regardless of your vehicle’s condition – because it’s the contact patch that converts intention into motion.

Navigating blind spots: from muddy trails to misjudged abilities

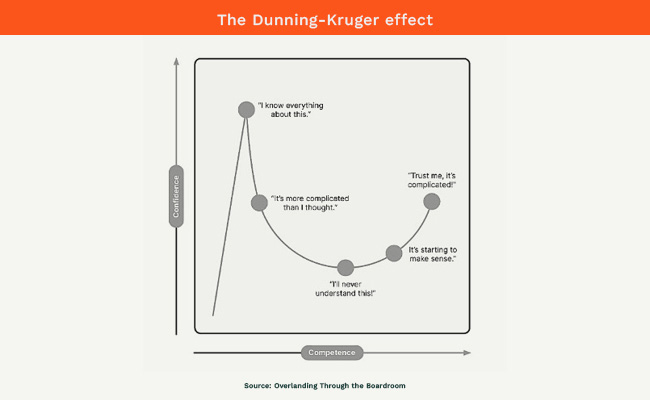

Thinking back to our unexpected challenges and detours on the way to Lake Malawi reminded me how often confidence gets behind the wheel, while experience and expertise slide into the back seat. It’s not just about a muddy trail or missing the sunset – it’s about how we measure our abilities while being blind to our own blind spots. There’s a name for this bias, and once you see it, you see it everywhere: the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Coined by social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999, the Dunning-Kruger effect observes that people with low ability in a particular task or domain tend to overestimate their competence, while those with high ability tend to underestimate it.

The irony is that the people most affected by it are often the least aware of it. Those who lack knowledge lack the very skills to recognise that lack. Meanwhile, people with genuine expertise know what good looks like and therefore tend to undervalue their own competence.

We’ve all met the first type: folks who think they know it all, yet whose actions speak louder than their words. They make poor decisions, misjudge situations or underperform when put to the test. The consequences can be costly – impacting their lives and the lives of those around them.

And we’ve all met the second: capable people who hold back. They lack the confidence to take risks or seize opportunities. They fail to recognise their talents, then look back with regret.

Ultimately, the Dunning-Kruger effect is about perception versus reality. When we overestimate our abilities, we make bad decisions or perform poorly. When we underestimate ourselves, we miss out on opportunities and fail to reach our potential. It’s a delicate balance – but one we have to get right if we want to succeed, whether in the concrete jungle or on the wide-open plains of Africa.

On the trail: where miscalibration bites

Overlanding is a humbling teacher because it compresses decision-making, time and consequence. Miscalibrate, and the feedback loop is unforgiving.

- Navigation. Overconfident travellers can set off without properly planning the route, daylight windows or fuel stops; they may misread a map’s scale or symbols, or assume that one bar of mobile signal equals adequate navigation. In dense forest or mountain terrain, that’s how people get lost or exhausted – and why a conservative turn-back time is a risk tool, not cowardice.

- Equipment. A vehicle’s capability lives where rubber meets road. Without traction, nothing else matters. People overrate power and underrate tyres, recovery points, a shovel, a tyre pressure gauge and a compressor.

- Local context. Cultural norms matter. In some African cultures, removing shoes before entering a home is customary; it costs nothing to ask, and communicates respect.

- Risk cut-offs. Deep-water crossings and recoveries punish bravado. Without the proper anchors, snatch straps, rated shackles and a plan for forces and angles, you’re one mistake from injury or damage.

That night near Mulanje, we made two classic mistakes. First, we cut our daylight margin too thin. Second, we let a confident GPS arrow override common sense. Credit to the Jimny’s low-range and light weight, the little thing danced across. But, if we’re honest, the result says more about luck and contact patch than judgment.

The short bridge to business: tyres, maps and margins of safety

Why does a muddy crossing in Malawi belong in a business column? Because the same calibration errors show up in boardrooms – only the feedback is slower and the mud is made of money and people.

Think of three trail lessons as leadership metaphors:

- Tyres are a strategy. The contact patch is tiny – four small footprints that translate power into motion. In companies, the equivalents are the everyday mechanisms that actually touch reality: cash buffers, customer service, data quality and on-time delivery. Leaders often obsess over engine size (ambition) and bodywork (branding) but underinvest in tyres (the humble systems that create grip). Underinvest there and you just spin.

- Maps are base rates. On the trail, a topo map, a sunset table and a fuel range note are base-rates – reality checks before optimism. In business, base rates are what have happened to comparable projects and companies, not what you hope will happen. If you plan a launch, hiring round or expansion without base rates, you’re night-driving with wishful headlights.

- Margins of safety beat bravado. Leaving a daylight buffer, carrying a shovel, checking water depth – these are small costs that buy big resilience. In companies, working capital headroom, realistic timelines and pre-mortems are the same thing. They look wasteful until the day they save you.

The Dunning-Kruger effect sits underneath all three. When leaders are new to a domain, confidence can outpace skill; when teams are very skilled, they can undersell what they know. The fix is not to distrust confidence, but to calibrate it.

A compact explainer you can use with your team

If you’d rather show than tell, try this three-minute primer at your next project kick-off:

What it is:

A bias where novices overestimate their ability and experts underestimate theirs. It’s a metacognition gap – the skills needed to do a task are often the skills required to evaluate it.

How it shows up:

Teams commit to unrealistic dates, underrate integration complexity, skip risk reviews and plan for averages rather than ranges. Experts on the team speak softly; confident newcomers talk loudly.

What to do about it:

- Elicit base-rates first (what happened the last five times we did something like this?).

- Run a pre-mortem (assume failure in six months; list reasons; design mitigations now).

- Name a turn-back time (the business equivalent of “no river crossings after 5pm”).

- Design a red team (someone has to try to overturn the plan).

- Track the contact patch (pick three to five operational leading indicators and review them weekly).

This isn’t bureaucracy; it’s tyre pressure and a map. It gives the novices a reality check and permits the experts to speak up.

The night we crossed anyway

I still think about that crossing. On paper, it was defensible: we had a capable little 4×4, low-range, traction control and a short stretch of mud. In reality, we were over our skis. We didn’t know the depth profile. We didn’t see the base material under the mud, the flow or the recovery options on the far bank. We didn’t even have a clear rule for when we’d turn around.

The Jimny made it, and, like most lucky escapes, the story got funnier with distance. But that’s the trap: survivorship turns a misstep into a lesson in pluck. If we’d bogged down in the centre, that story would read differently.

Here’s what I’d do differently next time – on the trail and in the boardroom:

- Arrive with margin. In Malawi, that means planning around civil twilight, not just sunset, and leaving a cushion for traffic, admin and surprises. In business, it means schedule float, cash days on hand and a decision checkpoint before the point of no return.

- Walk the crossing. On a river that’s literal: depth, exit angle, base material, snatch-point availability. In business, it’s a dry run: instrument the system, pilot with real customers, probe the failure modes.

- Set tripwires. “If we’re not at X by Y o’clock, we stop”; “If AR days exceed N, we pause hiring.” Tripwires protect you from your future, overconfident self.

- Respect tyres. On the trail, that’s the rubber, pressure and tread (and knowing when to air down). In business, it’s frontline contact points: first-response time, complaint rate, and on-time fulfilment. These are your contact patches.

None of this kills adventure. It enables it. We crossed that night because the vehicle had just enough grip for just long enough. A better plan would have made it less cinematic and more inevitable. There’s a lesson in that, too.

Why this matters now

In uncertain markets, overconfidence is cheap and humility is scarce. Boards demand growth; teams feel the squeeze; leaders are tempted to over-promise and “cross anyway”. The Dunning-Kruger effect doesn’t mean you’re reckless; it means you’re human. The work is to build habits that nudge you back to calibration.

The BBC engineer had it right: “Tyres, my son. Tyres”. Strategy is what touches the ground. Buy grip where it counts; air down your ego; bring a map; set a turn-back time. Do the boring things that make bold things safe.

Overlanding Through the Boardroom: Using Adventure Principles for Success in Business is published by Rockhopper Books.

Johan de Villiers is the leader of First Technology Western Cape, an award-winning IT provider in South Africa.

Read excerpts from other chapters

Chapter 1: The mindset factor

Chapter 2: The Swiss cheese effect

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Fantastic piece, Johan. That harrowing drive was the perfect story to illustrate the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The “tyres are strategy” metaphor is something that will definitely stick with me. It’s a powerful reminder to respect the fundamentals. Thanks for the great read!