Days before senior health officials told Parliament they planned to scrap medical-aid tax credits and introduce new levies to fund the National Health Insurance (NHI), they assured the High Court in Pretoria they had no intention of doing either.

The contradiction cuts to the heart of the ANC’s most divisive policy project. For many in the health industry, it shows the NHI is being driven by political optics rather than a credible effort to rebuild South Africa’s failing public health system.

“There’s political puffery in this,” says Alex van den Heever, adjunct professor at Wits University and one of the country’s leading experts on health-sector governance. “The ANC has to keep saying it because it can’t back down politically. But the fiscal framework required for the NHI is laughably unrealistic.”

In October, Nicholas Crisp, deputy director-general at the department of health, told judges in an affidavit responding to a court challenge by business group Sakeliga that the government had no plans to impose additional taxes or remove medical-scheme tax credits for at least the next 10 to 15 years.

Last week, he stood before MPs proposing exactly that.

The department is scrambling to fund a universal-healthcare system that private-sector estimates put at between R600bn and R1.3-trillion (and potentially almost double that). Health minister Aaron Motsoaledi has dismissed those figures, but his department – which has an annual budget of about R280bn – has said it would need at least R200bn more annually to roll out the NHI.

Van den Heever says the department hasn’t conducted a single feasibility study to prove its plan can work. “They can’t produce one,” he says. “If they did, it would show they can’t achieve the stated objectives.”

Curiouser and curiouser

In a June 2024 report titled The curious case of costing the NHI, Pieter Faber of the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) warned that the government still hasn’t “fully costed” the NHI and that its ambitions “fundamentally alter demand and supply rules”.

The Saica executive said “match-box calculations” show that providing care at current private-sector standards would cost anything from approximately R4,900 to R40,300 per citizen – pushing the price tag up to as much as R2.5-trillion a year. Even if the tax credits were removed, the state would fall woefully short.

With local government polls looming next year and public trust eroding, the ANC is positioning the NHI as proof that it still champions the poor, following its loss of majority in 2024’s national elections.

But to Van den Heever, the system looks like “another pot to plunder” in a state apparatus already gutted by graft.

The rot is evident in the government’s own numbers. Provincial health-department debts – known as accruals – ballooned from R16.5bn in 2020-21 to about R24bn in 2024-25. In Gauteng alone, unpaid bills total roughly R8bn, including at Tembisa Hospital, where billions were siphoned off through fraudulent contracts.

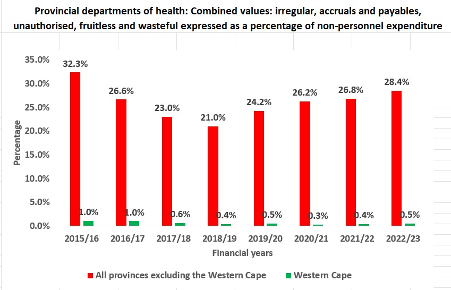

“Look at the accruals, but also the irregular expenditure,” Van den Heever says. “Provinces like Gauteng and the Northern Cape have irregular expenditure running at about R2.6bn to R2.7bn a year, every year since 2015-16. It never goes down.”

Those figures, he tells Currency, act as a proxy for corruption – and a warning of what could happen if billions more are funnelled into a central NHI fund.

“You’re giving a system that’s failing a bigger budget and fewer checks,” Van den Heever says. “The NHI does nothing to fix the governance crisis. It actually accentuates it because it keeps the political-appointment model that’s driving the corruption.”

The SAICA report paints the same bleak picture. Reviewing 1,427 public hospitals and clinics between 2011 and 2014, it found that only 6% met a 70% compliance pass rate, compared with 100% of private hospitals. The professional body said that, given worsening corruption and managerial failure, the gap has likely widened since then.

A system on the brink

For Craig Comrie, CEO of Profmed, that’s the real danger.

“We already know what happens when politics influences healthcare service delivery, leading to corruption and mismanagement,” he says. “Now the same group wants to nationalise the entire health budget. It’s a recipe for disaster.”

The Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF), which represents medical schemes and administrators, says the department’s tax-credit proposals are “contrary to any reasonable universal-healthcare model”, MD Katlego Mothudi said in an interview with Moneyweb.

Removing tax credits, the BHF argues, will trigger an exodus from private schemes into the collapsing public system – and end up costing the state more.

While the government frames tax-credit removal as a way to redistribute resources, the industry says it misunderstands how health financing actually works. According to the Council for Medical Schemes’ 2023/24 Annual Report, private medical schemes cover about 14% of South Africans, yet account for almost half of total healthcare spending – spending that eases pressure on the public system without costing the state.

If those members are pushed into public facilities, “the fiscal burden simply shifts from the individuals who pay for services themselves to the overburdened taxpayer who already pays too much tax for what they receive”, says Comrie. “It’s not redistribution – it’s a targeted collapse of healthcare by political design.”

South Africa, Van den Heever notes, has already reached its tax-capacity ceiling. “You can increase tax rates, but it won’t necessarily increase revenue,” he says. “You’ll just push more people into avoidance and evasion.”

Comrie agrees: “We’re going to have years of noise while the real fixes – mandatory cover for those who can pay, low-cost benefit options, proper governance – are ignored.”

With fewer than 7 million taxpayers carrying 60 million people, South Africa’s tax base is already stretched to breaking point – long before any new NHI levy. Personal income taxes supply nearly 40% of government revenue, while corporate and VAT receipts have stagnated – leaving a narrow middle class paying for nearly everything.

Meanwhile, public hospitals continue to collapse under debt, corruption and mismanagement, robbing the majority of the country’s Black population of life-saving services and basic medical care. At Tembisa Hospital, forensic investigations have uncovered more than R2bnn in irregular spending between 2019 and 2022 – from contracts where no goods or services were delivered, to overpriced gloves and phantom suppliers..

That, say critics, is the true face of state healthcare – and the reason many believe the NHI’s promise of equality is a political mirage.

Treasury has no choice

BHF was clearly “not in the room”, Crisp said in an email sent by the department in response to questions from Currency. Industry players “did not hear” that the presentation to Parliament was illustrative, based on earlier discussions with the National Treasury before the NHI Act was passed.

His explanation to the Standing Committee on Appropriations on October 28 was meant “to show the complexity and possible sequencing of funding reforms”. Instead of engaging, he said, “opponents would rather take our planning to court than talk to us.”

Crisp pointed out that there is already a legal basis for collecting revenue for the NHI Fund under section 49 of the Act. That includes the gradual phasing out of medical-scheme tax credits, a potential payroll or income-tax surcharge, and shifts from existing departmental budgets.

Treasury, he said, has no choice but to determine how the NHI will be funded, since the law is already in place, signed by President Cyril Ramaphosa just before the 2024 elections.

“Where would Treasury get a mandate to contradict both cabinet and parliament? It’s simply a matter of working out how to implement the Act.”

Taxes, he added, are still years away, as “many conditions are required to effect each funding shift”.

“We have no intention of summarily withdrawing medical-tax credits. A phased withdrawal will be required. We’ve discussed this with Treasury and looked at the implications of different thresholds for the initial withdrawal. Unless the collected revenue is earmarked for the NHI, there’s no benefit in shifting this funding stream.”

Private-sector ‘abuse’

Crisp said many people forget that the NHI will buy services from both public and private facilities, both of which “have massive structural and systemic problems”.

“Why is it not recognised, despite the clear evidence from countries all over the world, that we MUST NOT wait for perfect conditions to reform? Those conditions will NEVER arise.”

Provincial health departments, he said, must improve their systems with what they have, which “is ongoing regardless of the NHI”.

“But we’d like to hear from the media that the excessive pricing, fraud, waste and abuse in the private sector are also being addressed.”

Private role-players, he said, have “obstructed every attempt” to regulate prices, establishments and practices.

The health system “is in trouble”, he said. “Instead of finger-pointing and pontificating, parties should be sitting around the table and asking, ‘What can we do to help fix the problems?’”

Legal challenges mount

Officials have repeatedly defended the NHI as the only way to bridge South Africa’s two-tier health system – one for the rich and one for the poor – a system whose deep inequality finds its roots in apartheid.

For critics, though, the inconsistencies between what the government said in court and in parliament, continue to destroy what little trust remains between the state and the sector it’s trying to reform.

The Sakeliga case is one of at least eight legal challenges now facing the NHI. The cases, brought by groups including Sakeliga, the BHF, the Health Funders Association (HFA), Solidarity, and several medical schemes and professional associations, target both the constitutionality of the NHI Act and procedural flaws in how it was passed.

Some allege that public participation and parliamentary oversight were inadequate, while others argue that it violates constitutional rights to choose healthcare providers and enter into contracts.

Last month, the health department applied to have the cases consolidated into a single hearing, arguing that it would save time and prevent conflicting judgments. But those challenging the NHI objected, saying the move would delay justice and allow ongoing harm to the health sector by freezing all hearings until procedural issues were settled.

The dispute over consolidation will be heard in February 2026, meaning the main constitutional challenges – including Sakeliga’s claim that the NHI’s funding model is “irrational and undisclosed” – are unlikely to be argued before mid-year.

The uncertainty clouding the health industry’s future is not coming without a cost. Official figures show that between 2013 and January 2025, the public sector lost more than 12,700 doctors and nearly 59,000 nurses, according to Juta Medical Journal.

At the same time, thousands of newly qualified doctors are finding no place to work. According to the South African Medical Association (SAMA), at least 1,800 junior doctors who completed their mandatory service remain unemployed – forcing many to seek private practice, emigrate or wait in limbo. Health department data shows that of the cohort who completed community service in 2023, only about 60% — or around 1,187 — secured funded posts.

Comrie puts it bluntly:

“We’re trying to build universal healthcare on an illusion. But illusions don’t pay hospital bills – and they certainly don’t heal them.”

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.