That we should abolish poverty is not a new idea. But it is also not a terribly old one.

For most of human history, poverty was accepted as the natural state of humankind. We are born with nothing; everything beyond subsistence must be grown, made, or exchanged. To be poor was to live as nature intended, reliant on labour and the seasons. Wealth, by contrast, was exceptional, the product of expropriation. Poverty was not a moral failure but the baseline of human life.

That view began to shift in the late eighteenth century. As Martin Ravallion notes, the radical insight of the Enlightenment was not that poverty existed, but that it might be ended. Rousseau and Condorcet argued that inequality was not natural or divinely ordained but created by human institutions. Rousseau traced its origins to property and law; Condorcet believed that better knowledge and governance could reduce it. Jeremy Bentham and Thomas Paine took these ideas further. Bentham proposed progressive taxes that shielded the poor and placed greater responsibility on the rich. Paine outlined a land tax to fund universal stipends and pensions, an early version of basic income.

But it was economic growth rather than redistribution that mattered most. The nineteenth century saw progress against poverty in Europe and North America, driven by industrialisation, rising wages and, yes, the slow expansion of social protection. But it also saw new divisions about who deserved help. Britain’s Poor Laws created distinctions between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor, with workhouses designed to deter the idle. It was only toward the century’s end, with figures like Alfred Marshall, that poverty came to be seen as an ‘evil’ that economics itself might help to eliminate.

In the twentieth century, that insight became global: Roosevelt’s (not-too-successful) New Deal, Beveridge’s welfare state, the post-war consensus, and the 1960s ‘War on Poverty’ each turned the abolition of poverty into a matter of government action. By the time the UN’s Millennium Development Goals were announced in 2000, the ambition was universal: halve the global poverty rate by 2015 – and later, under the Sustainable Development Goals, end it entirely by 2030.

So how are we doing in the fight against poverty today?

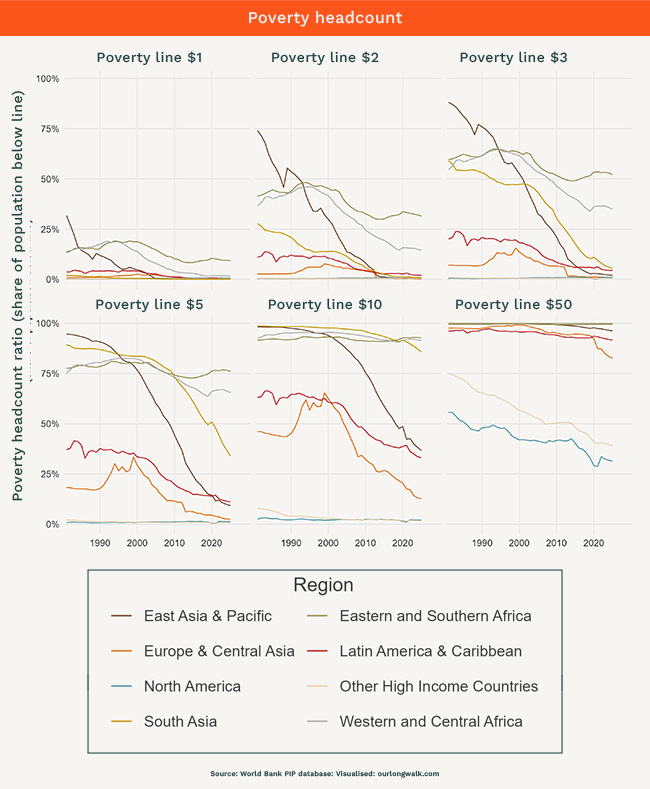

The World Bank has just released a new tool to analyse changes to global poverty since 1990. As the image above shows, across almost every conceivable poverty line – one, two, five, or even ten dollars a day – global poverty has fallen sharply. East Asia’s curve, led by China, plunges from near 80% to almost zero within a generation. South Asia follows more slowly. Latin America’s progress has been uneven but real. Even at higher thresholds like ten dollars a day, the long-term picture is one of rising prosperity. The world, in Ravallion’s phrase, has been engaged in a ‘Second Poverty Enlightenment’: the first time in human history that the majority of people no longer live in extreme deprivation.

And yet, one region breaks the pattern.

In the last few years, Africa’s lines – notably Eastern and Southern Africa – have flattened. At the lowest thresholds, progress is visible but painfully slow; at higher ones, it almost vanishes. Slow and volatile growth, fast-growing populations, weak infrastructure, limited industrialisation, and recurrent conflict. For all the talk of ‘Africa rising’, much of the continent remains trapped in poverty rates that East Asia escaped thirty years ago.

What, then, should be done? Growth remains the cornerstone. As the LSE’s Lant Pritchett argues, rapid, sustained, and inclusive growth in developing countries is both a necessary and, in most cases, sufficient condition for improving human wellbeing. We must learn to produce more with less.

But that’s easier said than done. This year’s Nobel prize in economics went to scholars who ‘explained innovation-driven economic growth’. It should not be all that surprising that these authors have hardly done any work on Africa. Those who do pay attention to Africa – development economists – may not always work on the questions that really matter. Here’s Prichett again, himself a development economist: ‘Most of the world’s poverty is not because the world is full of poor people but because people are living in poor places.’ The rise of randomised control trials has taught us much about what helps individuals – better teaching methods, cleaner water, small cash transfers – but little about what makes countries prosper.

That does not mean micro-evidence is useless. It has refined our understanding of what works within households and schools. But if the big question is how to sustain productivity growth across societies, then the answers must lie in what economists once studied more openly: technological diffusion and the institutions that sustain innovation. How does a society create a scientific culture? How does the process of industrialisation work in a deindustrialising world? How do states invest, regulate, and build trust? These are questions that cannot easily be answered through randomised experiments.

Take deglobalisation: the slow erosion of open trade and the retreat of capital into blocs. Or technology, particularly artificial intelligence, which could both deepen divides and open new opportunities. Or climate change. A recent paper by Joel Ferguson, Marshall Burke, Edward Miguel and Solomon Hsiang, for example, quantifies what a changing climate might mean for Africa. They find evidence of a ‘climate-conflict poverty trap’: warming reduces growth in already-hot economies and increases the likelihood of violent conflict, which in turn depresses growth further.

Under a moderate-to-high emissions scenario, the incidence of conflict is expected to rise by about five percentage points and the share of African countries experiencing negative growth by more than twelve points this century. They see roughly four additional years of conflict, on average, and in about one in eight simulations, countries end the century poorer than they began.

The reason is that the costs of conflict accumulate. Once conflict starts, the probability that it continues the next year jumps by over sixty points. In their model, the poorest countries experience the sharpest effects: a one-degree Celsius rise in temperature increases their risk of conflict by roughly eleven percentage points, while the richest see no significant change. Feedback loops – slower growth breeding conflict, and conflict further slowing growth – magnify the danger.

Yet the same study offers a glimmer of hope. Raising baseline growth by even one percentage point per year largely eliminates the risk of collapse. The difference between prosperity and stagnation, in other words, is small but compounding. Peacekeeping, political inclusion, and steady macroeconomic management – the dull work of statecraft – all matter because they keep countries within the high-growth, low-conflict zone.

Perhaps it is unfair to accuse the ‘randomistas’ of missing the point. Their experiments have improved lives, often measurably. But the most important questions remain those of scale. How to build productive states, to channel capital, to create incentives for invention – these are the levers that lift millions, not hundreds, from poverty.

Few in 1990 could have predicted how quickly global poverty would fall over the next 35 years, or how unevenly. The world learned that progress is possible but not guaranteed. If the next decades are to see Africa catch up rather than fall further behind, it will depend on whether governments will allow the conditions for sustained growth before the climate turns against them. The moral imperative that began two centuries ago – that poverty is not inevitable – still stands. But its fulfilment now depends on a race between compounding growth and compounding heat.

Top image: supplied

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.