The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) held interest rates this week in a decision that underscores how government-controlled prices are complicating the fight against inflation.

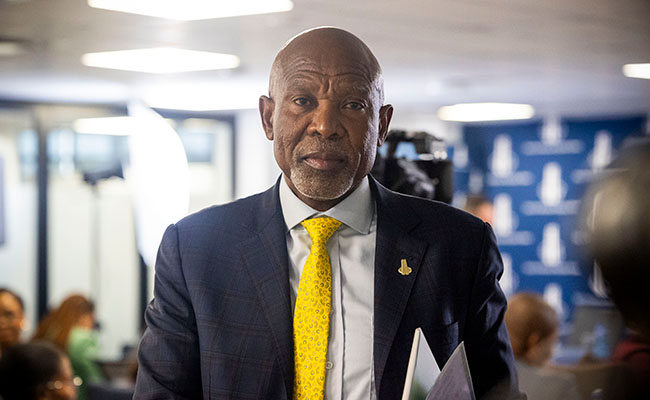

“This is a reminder of the serious dysfunction in administered prices, which undermines purchasing power and weakens growth,” said governor Lesetja Kganyago. “The solution to this crisis is not a higher level of inflation, but rather sector-specific reforms to improve efficiency.”

Kganyago said policymakers have to revise their inflation forecasts higher, with consumer price gains now seen peaking at 4% in the fourth quarter of this year, compared with a previous estimate of 3.7%.

The adjustment reflects how out of whack tariffs and charges set by state-owned companies, regulators and government departments are, set against overall inflation. Just recently, the energy regulator apologised for a R54bn miscalculation identified by Eskom that the SARB says will push up electricity prices by nearly 8%, and not 6% as previously expected.

The governor urged that state-controlled prices be reined in, “which entails engagement with the administered price setters”.

The pause comes after cumulative cuts of 125 basis points since September last year which have taken the SARB’s repo rate to 7%, the lowest since November 2022, and the prime rate, which is used by banks as a yardstick to set interest rates for their clients, at 10.5%. Two members of the monetary policy committee argued for another 25 basis-point reduction, while the other four opted to hold, citing the need to assess the impact of earlier easing and the risks posed by sticky food, fuel and electricity costs.

For Sisamkele Kobus, economics analyst at Ninety One, the decision was finely balanced. While the team at the country’s largest private money manager were expecting the SARB to hold, a lower-than-expected 3.3% inflation reading for August on Tuesday (from 3.5% the prior month) had some questioning their view – and not only at Ninety One.

“But our thinking was that in the second half of the year we’re moving into an environment where inflation trends higher,” she says. “We were expecting upward revisions to the SARB’s forecasts, and that’s what they’ve delivered.”

Food prices, which surged earlier in the year, now appear to be moderating, particularly in grains and vegetables, though meat inflation remains sticky. Global fuel prices and currency movements also remain wild cards. With inflation expectations easing among South Africans and the latest print showing “some food pressures behind us”, the stage is now set for “an interesting November meeting”, Kobus adds.

While the decision is a blow for South Africa’s heavily indebted consumers, it helps keep the country attractive to yield-seeking investors, says Citadel chief economist Maarten Ackerman. It followed a day after the US Federal Reserve cut rates by 25 basis points, potentially supporting the rand through “carry trade” flows — where investors profit by parking funds in South Africa, which still offers relatively higher returns than the US. The Fed has now cut rates by a cumulative 125 basis points since September 2024, the same magnitude as the Reserve Bank over the same period.

Speed up reforms

Elna Moolman, head of South Africa macroeconomic, fixed income and currency research at Standard Bank, sees room for more cuts if the SARB can see a path towards its projections for a decline in headline inflation towards 3.1% in the first quarter of 2027 and 3% by the fourth quarter of that year. “This is therefore not necessarily the end of the cutting cycle but rather a pause, with the Reserve Bank’s own models also implying that the bank could cut interest rates further if the inflation forecasts materialise.”

The bigger challenge, though, lies closer to home. The Eskom tariff misstep highlights not just the inflationary consequences of regulatory errors but also the broader need to speed up reforms in the public sector, despite some successes. Unless such problems are fixed, monetary policy alone cannot anchor inflation at the 3% level the SARB now prefers.

Unlike market-driven prices, administered prices are largely outside the SARB’s control and often reflect inefficiencies or political compromises in state entities. Electricity, municipal services, fuel levies and other administered charges account for a significant portion of household expenses.

Reform in these areas, emphasised Kganyago, is essential. The governor has repeatedly warned that without structural changes to how administered prices are determined, South Africa risks persistently higher inflation and, as a consequence, higher borrowing costs than its peers.

As Kganyago put it: “High inflation begets high interest rates. If we are to have low interest rates, we must have low inflation.”

Top image: Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago. Picture: Gallo Images/Alet Pretorius.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Thanks for the sharp, timely piece—you really bring into focus how the roots of macro-challenges often lie far deeper than monetary policy settings. The depiction of how administered prices set by state entities — such as tariffs, regulatory charges and utility rates — are contributing to inflationary pressures and undermining growth is spot on.