Strip out inflation, and the brutal truth is that you’re taking home 47% less money than a decade ago.

This is according to an index by debt management company DebtBusters that aims to determine the level of consumer stress in South Africa. In other words, while 2025 felt like a recovery, this is only a marginal breather after a period in which taxes spiked, salaries hardly shifted and grocery prices soared.

Salaries just aren’t measuring up, says DebtBusters COO Benay Sager. While net incomes inched up 2% over the past decade, inflation has grown 49% in that time – leading to a stark discrepancy.

To cope, South Africans have taken out loans to supplement the shortfall.

“Loans are lifelines – they are very, very vital to supplement the shortfall in income where people are really facing difficulty,” says Sager in an interview with Currency.

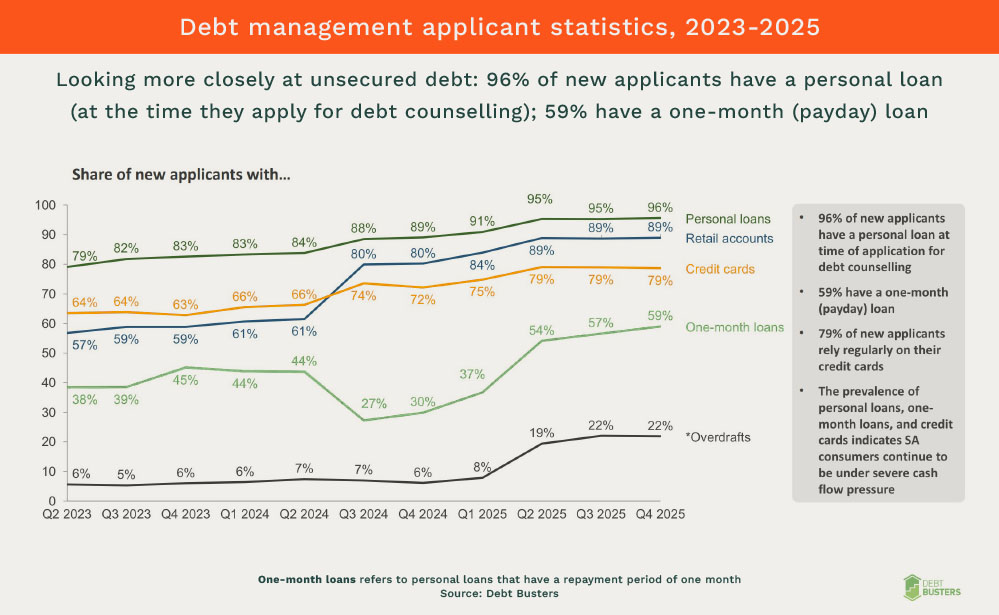

Sagar says 96% of those who come to DebtBusters looking for help restructuring their debt had a personal loan – often taken out at eyewatering rates – while about 60% had a one-month payday loan, typically given at rates likely to bankrupt you.

Not keeping up

It’s the household debt crisis few are willing to confront. But stories from chat forums, like Reddit’s personal finance forum, reveal how bad it is on the ground.

“The last two years were a whirlwind,” said one person, who didn’t provide their real name, but whose personal debt has rocketed to more than R220,000. “I am able to pay the monthly instalments, but I don’t have any income in the end, which leads me to spend on my credit card. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Someone else, a 30-year-old man known only as “FlakyTie”, said he has rung up R250,000 in debt. “I’m starting to lose my mind here,” he says. “Payments are roughly R15,000 a month, which leaves us about R10,000, which doesn’t cover all medical expenses, groceries [and] transport.”

This, he said, has had dire consequences for his mental health. “This has spiralled me into a depression, and I don’t know what else to do.”

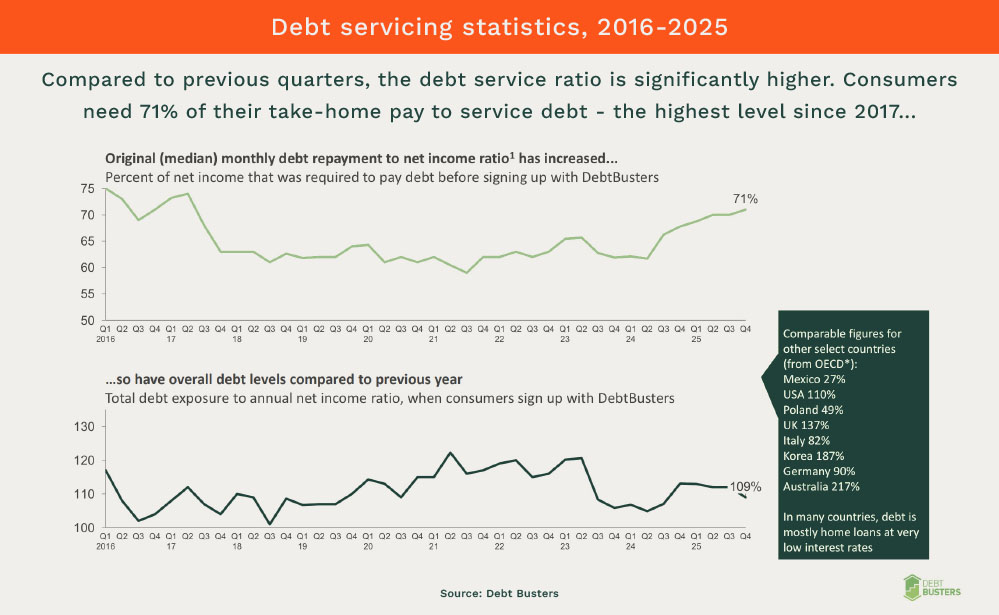

Evidently, he is not alone. On average, South Africans need to use 71% of their net income to service debt – the highest figure seen since 2017. For higher earners – those whose salaries exceed R35,000 a month – this shoots up to 85%.

‘Too much of a good thing’

Ominously, more South Africans are taking out unsecured loans, which don’t require collateral and are typically offered at high interest rates of more than 22% per year.

David Woollam, the former finance director of African Bank, says unsecured loans were initially intended to expand access to finance for South Africans. But, he says, “too much of a good thing can be very dangerous”.

Many South Africans can’t afford to pay the 22% interest rate and end up having their wages garnished.

“It just got way, way too big,” says Woollam.

“People were able to access hundreds of thousands of rands of unsecured loans, payable over seven, eight years in some cases. And in many cases those loans were not productive loans, they weren’t being used to acquire assets.”

Instead, these loans were used to simply finance people’s day-to-day existence, without the real prospect of their lives improving.

The upshot: consumers now have nearly 30% more unsecured debt than they did a decade ago – which jumps to 75% for higher earners.

Look outside the banking sector, and the costs of personal loans are often far higher, pretty much ensuring South Africans become locked into a debt trap of taking out new loans to pay off the previous debt.

“Some of the interest rates people are quoting to me are somewhere around 50%-60% a month, says Warren Ingram, an author and personal finance expert. “That kind of debt level is catastrophic.”

People will often pursue these types of loans as banks deem them too high a credit risk.

But, says Ingram, this only makes things worse. “People in desperate trouble go after an even more damaging solution because they don’t have another resource,” he says.

Scant relief

Despite all this, Sager insists things are actually better than they have been, as South Africa’s economic situation has improved.

“Interest rates were reduced multiple times during the course of the year. Now we’re looking at 150 basis points reduction in the last 15 months or so.”

But while the repo rate has been steadily declining since mid-2024 to 6.75% now, this may have come too late for many South Africans, who are now locking into the vicious debt cycle.

The two-pot retirement system, introduced in 2024, which allowed people to access R30,000 from their pension savings once a year, has helped. Sager says this isn’t the ideal solution, but “it’s still probably a better option than the previously available version, which was resign from your job and access 100% of your savings”.

Inflation is also relatively low right now, at about 3.6%, which has kept the cost of living in check. Last week, the Reserve Bank confirmed as much, saying that “inflation expectations have fallen”.

Still, for the average person on the street, the dip in inflation might not feel like much – particularly for poorer South Africans, whose effective experience of inflation is two to four times higher than the official rate indicates.

Ingram says the lower interest rates will help, as will the prospect of higher GDP growth. But, he adds, “does it make a difference to me and you tomorrow? No.”

Going for broke

Gambling hasn’t helped.

Sager says the growth of this activity has been “stratospheric”. Many of those who come to DebtBusters for help have turned to gambling to make ends meet, with dire consequences.

“You’d be hard pressed to find someone who doesn’t have any money allocated to gambling apps,” says Sager.

DebtBusters says the bank statements of those in its programme reveal repeated deposits into gambling apps of R500 all the way up to R25,000.

Ingram says he has been shocked that even those battling to service debt at 50% interest rates still find money to gamble with.

“The logic is that you could get back 10 times what you bet,” he says, which pushes those already in debt to try and find a way out.

According to Stats SA’s consumer price index, gambling ranks as the 12th-largest household expense nationwide – sitting above several more basic necessities.

Sager says the solution is to focus on those things “that we can control”.

And he points to rays of light: the number of people successfully clearing their debt is now 12 times higher than it was a decade ago, he says. Which is a helpful sign of maturity when it comes to managing credit.

But still, with far less money to go around, and South Africa’s economy having failed to properly ignite, the trajectory out of debt is far from obvious.

ALSO READ:

- The SARB’s review of prime will not reduce the cost of debt

- A R1.5-trillion habit South Africans can’t afford

- Cracking the credit score code

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.