The global sportswear market is vast and still growing. In 2023, it was worth a cool $380bn; this year it’s expected to hit $433bn in value. You’d expect those kinds of numbers to mean a sure-fire investment case for listed players in the sector, yet it’s been a bruising time for two companies in particular: Nike and Lululemon. Set against the context of rising global demand, both companies look cheap. But the question is: which is best placed to turn that situation into shareholder returns?

Lulu – a real lemon

Shares in Lululemon, the once-insurgent turned incumbent, crumpled over 17% earlier this month after it cut its earnings guidance for the rest of the year.

It takes the company’s decline to 50%, year to date and, at about $170 apiece, the stock is a horrifying way off the record closing high of $511 that Lululemon hit in December 2023.

CEO Calvin McDonald was blunt in the company’s latest earnings update: “We have become too predictable … and missed opportunities to create new trends.” Management also highlighted a $240m hit to gross profit from tariffs and the end of de minimis exemption in this update (a US rule that lets imports valued at $800 or less enter duty-free with simplified customs).

But it wasn’t all disaster, considering that revenues grew almost 7%, helped by solid international sales. It’s a reminder that when the news is in the price, what moves stocks is a change in trajectory.

Nike – comeback kid or end of an era?

Then there’s Nike. Its shareholders, you sense, are fatigued: the stock is roughly flat year-to-date and is well below its five-year highs. Nike’s shares peaked at a record closing high of $177 in November 2021 before a long grind lower to about $70 today as strategy and product missteps met tougher competition.

One of Nike’s problems was its over-emphasis on a direct-to-consumer model (by steering buyers to Nike’s own channels like Nike.com), which frayed existing – and important – wholesale relationships with big sportswear retailers. Where before the wholesaler – like Dick’s Sporting Goods or Foot Locker – would have handled the costs of delivering and packing orders, processing returns and running the payments platform, Nike took these functions on. The result? It ceded shelf space to competitors, and the much-anticipated margin expansion that was supposed to materialise simply didn’t. What’s more, its pace of innovation also slowed against its rivals with some products becoming stale or overplayed while growth in some regions, like China, was patchy.

New CEO Elliott Hill now has a short window to show a clear shift in direction before the pressure intensifies. His plan hinges on re-engaging wholesale partners, driving new product innovation and refocusing on performance product with many analysts expecting the turnaround to hinge on reviving core running brands (like Pegasus, Structure and Vomero).

Speaking of successful turnarounds, the Springboks, resplendent in Nike kit, offer interesting parallels to Nike’s current troubles and show that a downturn in performance doesn’t have to be permanent. Indeed, most South Africans can vividly recall the lows of the mid 2010s but what, at the time, seemed like the permanent end of an era turned out not to be so, with a change in leadership and new strategies yielding results which culminated in the Boks lifting back-to-back Rugby World Cups in 2019 and 2023.

Like the Boks, if Nike can confront its issues, and build a plan that the team can get behind and execute week in and week out, the results should follow.

Winning sells

“Nike’s story starts with the athlete story. It always has. And it always will,” said chief marketing officer Nicole Graham in 2024.

In sport, as in investing, winning matters. For Nike, Michael Jordan is the timeless case study in performance turning into product and profit, with the Jordan brand generating roughly $6.6bn of revenue in FY2023 (about 13% of Nike’s total that year).

The Messi effect is another example, with adidas reporting “extraordinary demand” for Argentina/Messi shirts around the 2022 Fifa World Cup final, with stock sold out in multiple countries.

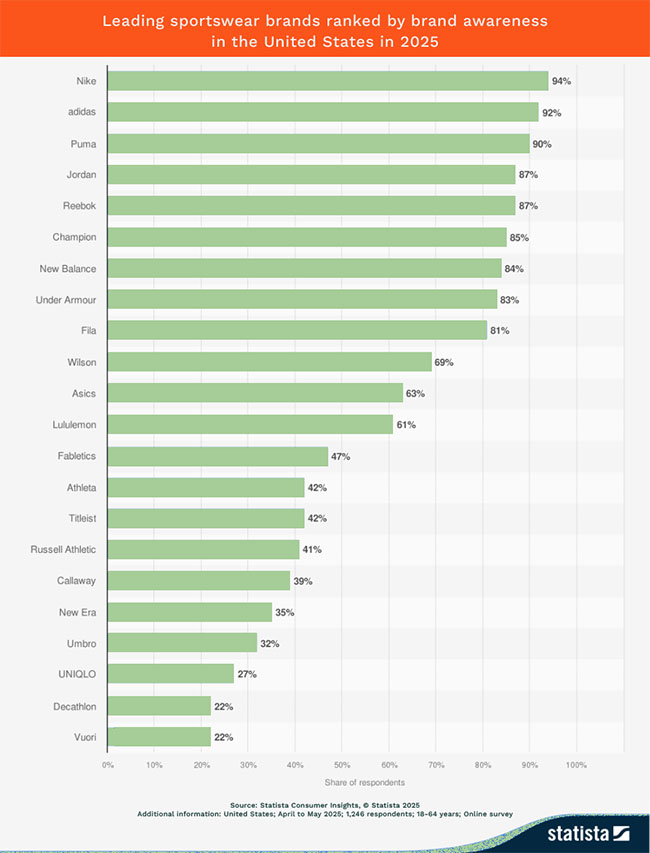

Of course, not every brand needs an athlete’s halo to sell leggings, and Lululemon has built a formidable community engine. But for most of this industry, signature wins are the shortest route to consumer consciousness, and ultimately market share. That’s why the brand-awareness leaderboard still tilts to legacy winners like Nike: years of televised victories put logos on highlights reels and into memory.

Rotation or regime change?

Arguably, the share price declines of both look more like a rotation out of the companies into rivals than a wholesale regime change. That is, unless Nike and Lululemon keep missing on product design and distribution. Scale still compounds in this industry with distribution reach, strong athlete portfolios, and vast R&D and marketing budgets all providing durable advantages over newer brands.

For Nike, fixing its specific issues could have an outsized impact, so even modest market share gains on a huge base can shift the story. Consider that a return to its prior share price highs would imply 140% upside from current levels.

For Lululemon, the challenge is expectations more than relevance. If new designs and products are well-met and the US segment stabilises, the upside is considerable: about 200% upside to its previous highs.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.