This week, Pick n Pay CEO Sean Summers added his voice to an increasingly strident chorus of businesspeople speaking out against online gambling, controversially suggesting advertising should be banned. In my humble opinion, this is an awful idea that smacks of hypocrisy, virtue signalling, and terrible economics.

Summers is by no means the first and won’t be the last to call for online gambling to be “brought under control”, and personally, I’m not averse to light regulation; I understand the dangers of gambling addiction and how it can exacerbate poverty. Summers’ views were echoed on Currency by Thomas Brennan, a co-founder of Franc, a South African fintech, who argues online gambling campaigns “normalise risk and glamourise loss” and calls for tobacco-style advertising restrictions.

But the crisp issue is this: to what extent should the government protect people from themselves?

Part of the problem is that the numbers being thrown around are so obviously rubbish; it just offends me that there seems to be absolutely no attempt to understand the fundamental dynamics of the issue.

The first dubious number is that gambling is now hoovering up R1.5-trillion in revenue a year. This comes from the latest annual report from the National Gambling Board, published in August, which found the total value of bets placed rose from R1.1-trillion in 2023/2024 to an astounding R1.5-trillion in 2024/2025, a whopping 46% annual increase.

But this is not the industry’s profit or even the amount punters lost. This is the amount bet, and we know why it’s so large. When you bet on Manchester United winning a soccer match (I know, crazy, but people do) and you win (astounding, but it does happen, like last week against Brighton), what most people do is bet that money again. All those repeated bets mount up.

Not Monty Python’s parrot

If R1.5-trillion were the amount punters lost, the South African economy would be the parrot in the famous Monty Python sketch (not that this is entirely untrue); that’s equivalent to half of total government expenditure. It’s a number so huge that it is obviously bogus and is plainly being used to make South Africans, particularly government regulators, hyperventilate over the issue. The fact that this number is plonked on the table should in itself be a warning sign.

Summers says somewhere north of R70bn is being “taken out of the market” by the gambling industry. His incentive is obvious: he means that R70bn is being taken out of his market – the supermarket industry. It’s not being taken out of the gambling market; it is the gambling market.

You might as well say another industry – let’s call it the retail industry – is taking R70bn out of the gambling market by irritatingly providing a service people actually want.

And is that number even correct? The big players are not listed, so the numbers are not available, but Sun International is listed, and its online division, SunBet, had income of R1.2bn for the 2024 year (up a dazzling 60.6%!). Ebitda on that turnover was R363m (an eye-watering 33% margin). SunBet is probably 5% of the total industry, so the after-tax profit of the total online industry is probably about R7bn, I would estimate.

That’s big, but it’s not, say, the retail industry, which actually takes around R70bn “out of the market” – i.e., in profit – and hands it over to shareholders, who then reinvest it, and so on.

The other number often cited is that about 20% of social grant payments are now being spent on online gambling. But once again, that is not the amount lost on gambling; that is the amount bet. Gambling institutions have a net margin much higher than supermarkets, but not that much higher than most other industries, and certainly not higher than parts of the IT industry. It’s true, the house always wins, but anybody who knows anything about the gambling industry knows that if gambling houses gouge their customers, their customers stop betting. It’s a bit like the retail industry.

And this relates to the larger question of protecting people against themselves. By citing the 20% of social grants payment number, Summers (I’m picking on him, but there are lots of people who strongly agree with him and have cited the same numbers), the implication is that South Africans are “addicted” to gambling, and that gambling is an “addiction industry”. Brennan says much the same: “Like tobacco before it, gambling companies sell addiction through sleek marketing, exploit weak regulation, and profit from dependence.”

Except there is a difference. Smoking is actually physically addictive. For the most part, gambling is fun, and of course, fun is addictive, but the comparison is specious. International figures suggest that only around 1% of gamblers are “addicted” in the sense that they struggle to stop betting and incur harm to themselves and their families as a result of gambling. That’s still a huge number of people, and obviously, the industry should take care here, as it does to a particular (inadequate) extent. But the irony is that actually finding these people and getting them help is much easier online than it is in the casino context.

But even if you agree that the industry should be carefully regulated (as I do), the worst part of Summer’s argument is that this regulation should be enforced through an advertising ban, and we know this is a terrible idea because of the long and involved anti-smoking saga.

The smoking example

An enormous amount of research has gone into South Africa’s anti-smoking campaign, and I’ve written about it extensively – partly because the clampdown, combined with poor management and enforcement, has created a huge, deadly and fabulously profitable illicit cigarette market.

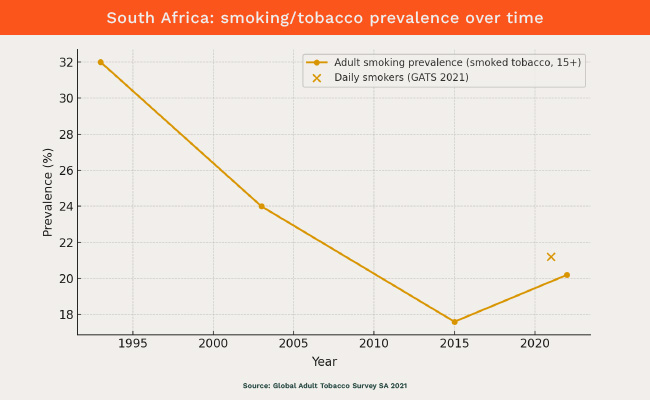

Smoking rates steadily fell from more than 30% of adults in the 1990s to about 18% by 2015, before the decline ran out of steam – and even ticked up slightly, according to the 2021 Global Adult Tobacco Survey. Two decades of restrictions later, the figure has settled stubbornly at around 20%.

What caused that initial drop? Evidence suggests South Africans – like smokers worldwide – responded far more to tax-driven price hikes than to advertising bans, which appear to have had almost no measurable effect. Of course, this finding is complicated; price increases, changes in social attitude, better population education, and the outrages of the smoking industry itself all contributed to much lower smoking levels around the world.

To me, the fact that after decades of virulent anti-smoking legislation, the habit still endures – with about one in five adults still smoking – is an indication not of how effective the campaign has been, but how ineffective even the most stringent state intervention can be.

But among all these measures, the advertising ban is the most egregious because it was the least effective and had the effect of freezing the industry. It’s weird that after seeing the tobacco mafia establish itself in South Africa, become the dominant seller of cigarettes in the country, see the illicit industry bypass billions in excise taxes, and people still think it was a success!

Nobody benefited from the advertising ban more than the existing tobacco industry, which has grown massively in profitability in the “advertising ban period” for the obvious reason that it made it impossible for any newcomer to challenge the existing industry. The ban drew up the moat and allowed the industry to bump up its margins. The advertising ban had the effect of enormously strengthening the existing industry.

Just for example, British American Tobacco’s revenue has increased by about 30% over the past decades, and its profitability has more or less doubled over the same period. There have been lots of ups and downs, of course, but the point is: one thing we have learned from the anti-smoking campaign is that what is required is a social consensus, combined with more education and sensible regulation. I also think people who lose money betting on sports will mostly learn their own lessons, which will be far more effective than the government jackboot. The freedom to make mistakes is also the freedom to learn, and that is an enormously penetrating social lesson.

In short, a gambling advertising ban effectively infantilises gamblers, risks establishing underground operators, and prejudices potential new competitors. If Summers is so opposed to gambling, one thing he could do immediately is remove the sale of National Lottery tickets from stores, which he has been selling for decades. You can’t help feeling he raised the issue at the Pick n Pay results because he wanted to talk about something other than the Pick n Pay results.

And just by the way, in case you think I am arguing against an advertising bad because this publication would benefit from it, Currency has just turned down a Hollywood Bets campaign because its return requirements were beyond what our advertising department thought would be worth it for the publication. That doesn’t mean Currency will never accept their advertising, but it does mean this is not an industry so rich that it is splashing advertising around thoughtlessly – and that is instructive in itself.

Online gambling, like alcohol or speculation, is a mirror. It reflects both the best and worst of human nature – our appetite for risk, our longing for reward, and our susceptibility to illusion. The case for it is rooted in freedom and economics; the case against it should be rooted in compassion and realism, not hyperventilation.

Top image: Rawpixel/ Currency collage

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

Well done Sean Summers. Gambling is so so damaging to society. Stats indicate that some 95% of people who gamble, cannot afforfd to do so. The are using “food and living ” money in an absolute gamble to acquire wealth. The advertising is tantalising and tempting, the chances of return are minimal. Gambling is destroying families.

Online gambling MUST be banned completely, period! It is so much easier to load money directly from your bank. Call it easy access. Just keep loading… Not always so “convenient” to drive to a land casino.

Check out this article on the harms of sports betting adverts

https://news.sky.com/story/i-gambled-away-1m-two-marriages-and-tried-to-take-my-life-but-im-still-seeing-adverts-13352158

I believe that advertising for gambling should be banned as is the advertising of cigarettes. You can still smoke and buy cigarettes and you should be able to gamble but, yes, sadly we do need to be protected against ourselves. Cigarettes was damaging to our health but you had to smoke hundreds of cigarettes over many years for the affect to be obvious. With gambling, in just a couple of hours a person can wreck their life and more than likely that of their entire family. Sadly, too, it is the people who can least afford to gamble that want ‘to take a chance’ but it is as addictive as nicotine and the consequences are worse.

Excellent, thought provoking article – content on Currency News is a step above many other SA financial and business news sites at the moment.

Perfectly reasonable to ban advertising that compels people to engage in an activity that ruins their lives and harms their families. You can do so without infringing on their autonomy an iota.