Many who write about business and finance admire a columnist named Matt Levine. He writes the “Money Stuff” column at Bloomberg News – a constant marvel of razor-sharp analysis and gentle humour about subjects that might otherwise be eye-glazing.

Some time back, during the dizzying madness of the digital art non-fungible token (NFT) era – when unremarkable cartoon images were selling for eye-watering prices because they were entangled with a newfangled crypto whatnot – Levine set to work trying to understand what an NFT actually was.

After a great deal of analysis, probing, reading, interviews, application of financial nous, and searching for the right words, he finally arrived at his eureka moment to explain NFTs: “Oh. I get it. It’s a receipt.”

Indeed, an NFT is a receipt for the item you bought. That’s basically it. It is a deed of ownership, if you prefer more highfalutin language. If you bought a digital cartoon image of a cigarette-smoking ape, you got a receipt – an NFT – lodged securely on a blockchain, which proved you owned the ape, and to which only you had access.

Behind the realisation that the token is merely an ownership certificate, a massive industry has been launched, one that will likely eclipse bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. It is (somewhat clumsily) referred to as real-world asset tokenisation, or more colloquially, RWA tokenisation. The token being an NFT.

Before I describe the shape of this new industry, a word of clarification about the NFT: the deed of ownership. It is digital. It lives on a blockchain. It is secure. It is unhackable. It can be frictionlessly transferred or sold by the owner on a public NFT market. And it can be tethered to an arbitrary number of conditions, like “you cannot sell this item on a Tuesday”. These conditions turn out to be critical – they make the ownership terms “elastic”, allowing them to be designed with almost infinite flexibility.

This is not generally true of other old-style deeds of ownership, like houses, car registrations, or even the receipt for the shoes you bought at the mall. It opens up an unprecedented world of new tools for financial packaging.

Fastest-growing market

This brings us to the big aha moment that is occurring now. In the world of traditional finance, the issuance of assets has always been accompanied by a dispiriting amount of legwork and expense.

The listing of shares for sale on a stock market, for instance, is a lengthy, frightening, paperwork-heavy, wallet-emptying journey. Or, more prosaically, the sale of a home involves agents, municipalities, registrars, escrow, conveyancers, and so on. Further up the financial chain, the syndication of a loan to finance the construction of a manufacturing plant requires originators, banks, depositories, underwriters, middlemen – and more middlemen.

Recent research shows that for the issuance of a large financial asset, as many as 30 parties can be involved, from origination to distribution – all taking their pound of flesh. The process is ossified, labyrinthine, inflexible and, in some cases, corruptible.

Enter NFTs. If the original asset can be split into hundreds, thousands, or even millions of secure tokens of ownership (NFTs), each representing a fraction of the asset, and then lodged and traded on a blockchain (and perhaps tied to special conditions like the release of a yield at the end of each month), then the whole enterprise becomes vastly simplified – to say nothing of widening the buyer base to investors who may want to spend only R1,000 to own a tiny piece of a billion-rand private credit deal (simply not accessible via traditional finance).

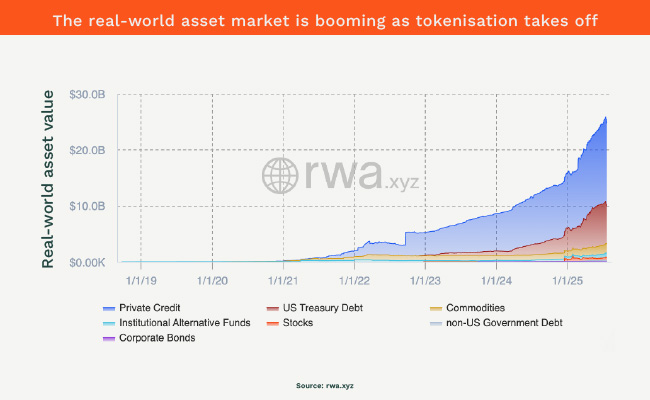

And so, over the past two to three years, we have seen an increasing number of RWA tokenisation projects, with assets offered for sale through the mediation of a secure blockchain for lodging, trading and lifecycle management. In all imaginable sectors, asset issues are being tokenised: treasuries, property, funds, loans, collectables, artworks, private credit, commodities and more.

Major research and forecasting firms project rapid growth. For example, BCG and ADDX estimate that the tokenisation market could reach $16-trillion by 2030, while Security Token Market and others forecast up to $30-trillion in tokenised real-world assets by that year, making it by far the fastest-growing new financial instrument in history.

So how is it going, a mere few years into the industry? The chart below from analytics firm RWA.xyz paints the thousand-word picture.

The industry is about to go parabolic. Big traditional players like BlackRock and Franklin Templeton are already neck-deep in tokenised issuances ($2.5bn and $780m respectively), while lesser-known new players with crypto heritages, such as Ondo and Paxos, swim competitively in the same pool. The losers? Banks and investment companies that are too slow to adapt to this fast-moving financial juggernaut. Oh, and of course, the middlemen. They lose – and we thank them for their service.

In South Africa, no banks or large investment houses are seriously playing in this space, though a few smaller independent companies, such as RainFin, Mesh and Ramdev, have started issuing tokenised assets over the past few years. Cryptocurrency exchanges VALR and Luno have also announced upcoming tokenisation projects.

And what of those digital art NFTs from a couple of years ago? Bored Apes and Pudgy Penguins and the like? They are still there, still trading – but well off their tulip highs. NFTs have evolved and matured. There is always a market for everything under the sun. NFTs and the blockchain just make it easier, faster, cheaper, safer – and, most importantly, open to anyone.

This article was produced in partnership with Binance.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.