Pauli van Wyk has been a towering figure in South African investigative journalism for more than a decade. She has clashed with some of the most nefarious characters of post-democracy South Africa, working on the GuptaLeaks, laying bare how Tom Moyane unravelled the South African Revenue Service (Sars), as well as how banking group Sasfin allegedly facilitated money-laundering for tobacco baron Simon Rudland.

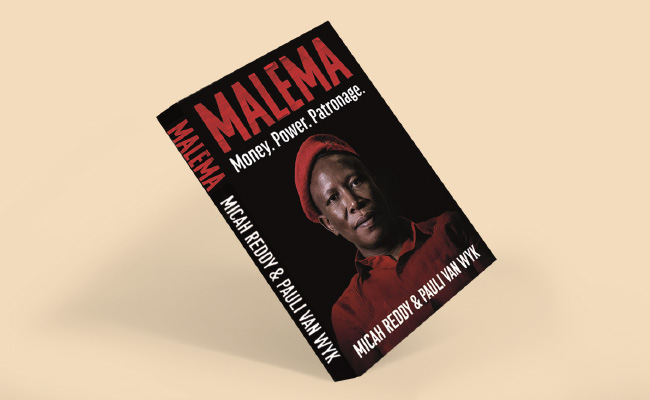

But it has been her investigations into Julius Malema, the populist leader of the EFF, that have caused the biggest waves, revealing in scrupulous detail how Malema and Floyd Shivambu apparently benefited from the R2bn bank heist of VBS Mutual Bank. This month, she and fellow journalist Micah Reddy released Malema: Money, Power, Patronage, a book that reveals in devastating detail the deepest secrets of the empire Malema has built.

The top lines are sensational, such as the fact that Malema, a politician, has somehow managed to amass a R21m property portfolio, but the book goes far deeper than that. It is part tragedy – how the most talented political leader in post-apartheid South Africa derailed his potential by ostensibly choosing corruption over public service – part social commentary on the consequences of impotent law enforcement, and an absorbing psychological study of a man who could still become president of the country. Van Wyk spoke to Currency.

Ever since you began to report on Malema, you have been vilified by his supporters. A University of Sheffield study of the abusive threats targeted at you said 46% of it was designed to discredit you professionally, and ‘mute freedom of expression’. To what extent did the potential for a new round of threats worry you when writing the book?

I really didn’t give it much thought; it was a difficult book to write in other ways, but not because of that pressure. Which isn’t to say those attacks weren’t hectic. To hear Malema tell his supporters I should be raped and hanged, that I’m a witch and anti-Black, was really horrible. But once it clicked in my head that this was just a tool he uses to scare me so that I’d back off, it got easier for me to handle. He’s really quite a master at manipulation, so he reframed it as a case of me not wanting him to wear Gucci, or have a nice house, which wasn’t true at all – what I didn’t want was for him to steal money, break the law and be corrupt.

People who write books say you only actually do this when you can’t avoid doing so any longer, when the story is too big to avoid. Did you feel a similar compulsion here?

For sure. I felt I had to write it because, while there have been scattered accounts of what Malema had done over the years by people like Sam Sole and Stefaans Brümmer, Adriaan Basson, Fiona Forde, Piet Rampedi and others, there was no singular account that explains all of what he did and why. And I had lots of behind-the-scenes information that had never been published, including documents detailing the alleged fraud committed at the company he owned, On Point, back in 2011. So that had to come out. And finally, we wanted to write it to counter the view that after the On Point fraud, Julius had somehow reinvented himself. The truth is, he just got smarter … The VBS cases suggest that he learnt how to keep his fingerprints off everything; they suggest he learnt how to use power to threaten, cajole and solicit kickbacks. And that’s been his big reinvention over the past decade.

Malema was criminally charged in 2012 for fraud of R52m relating to how On Point won government contracts, yet after three years of needless delays by prosecutors, the case was struck from the roll. Had the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) done what it should have done, and taken the case to its conclusion, could we have avoided the VBS Mutual Bank fallout that came in 2018? Was this cowardly decision the original sin that gave rise to years of impunity?

For the NPA to say it didn’t have enough evidence to proceed, when it had signed affidavits from people inside Lesiba Gwangwa’s office who had allegedly paid kickbacks to Malema is just bullshit. And that decision was a watershed for the country because the NPA’s decision to shy away from prosecuting Malema helped really entrench the culture of impunity in the country. Every year after that, Jacob Zuma got stronger, and while you would have thought that this would be bad for Malema, since they’d fallen out, Malema was one of those who benefited from this culture of failing to confront the corrupt. And today, we’re dealing with the consequence of that, where none of the authorities are willing to confront Paul Mashatile, [the late] David Mabuza or even Cyril Ramaphosa on the Phala Phala case.

You make a critical point about lawlessness in our society – but is the inability of the NPA and Hawks to tackle Malema for corruption due to a lack of skills, or a lack of courage?

It’s both. In 2015, Glynnis Breytenbach, who is now a DA member of parliament, was prosecuting Malema’s case, but she was removed, and the NPA put two junior prosecutors on the case – and it was a fucking disaster. They were too young, too inexperienced, and were trying to prosecute a case which the Hawks had done a shitty job of investigating in the first place. But it is also true that nobody was brave, not in the Hawks or the NPA. I remember speaking to an investigator at the Hawks, and it was very clear that they just weren’t willing to touch him, partly because some of them revered the guy, while others were worried he would be able to intervene to get them fired. If most people have a fight-or-flight response to being challenged, Malema’s response is absolutely to fight – and he does this so aggressively, and publicly. He humiliates people, and nobody likes this, so they find it easier to just avoid this risk.

On the culture of impunity, how hard is it to keep exposing corruption, and watch the very people you have exposed go about their business as if nothing happened? Former chief justice Raymond Zondo spoke, for instance, of how difficult it was to swear in ministers of Ramaphosa’s administration, knowing the findings he’d personally made against them on state capture. It must be the same for you?

It is disheartening. It’s actually harder to manage emotionally than the threats I’ve had. Malema is the ultimate Gucci revolutionary – he’ll seem incredibly generous by buying people wheelchairs who need it, but those people don’t know they are being given “charity” from money ostensibly stolen from them. If they knew, I’m sure they’d care very much.

And yet, the consequences might not be as emphatic as we’d want, but the revelations around VBS have made an impact, and it has filtered into the public consciousness. People I spoke to in places like KwaZhakhele and other townships before the last election said that while they attended the rallies, they wouldn’t vote for him because they considered him corrupt.

Yes, I hear this too, and I do think the level of trust in Malema has fallen due to all these revelations. He has tried his best to reframe this, but VBS remains an albatross around his neck. The middle class is mature enough to realise when they see unfair race-baiting – they have other problems, like are their kids safe, are their cars not being stolen, how can they pay school fees. Somebody in the last few days said it best: Malema is like that drunk uncle you allow into your family because sometimes he speaks the truth – but you’re not going to allow him to be the family patriarch because he’s a fool and fundamentally untrustworthy.

Does this mean Malema is done politically? After all, the EFF’s support fell to 9.5% in the last election, from 10.8% previously.

This is something Micah and I deliberated over quite intensely. You can never write off Malema’s ability to lift himself back up – he is the most talented politician in the country – but to do that, he has to reinvent himself and extricate himself from this gilded cage of corruption he has created for himself. He will need to stop flip-flopping when it’s convenient for him, he needs to show he’s not corrupt, and he needs to demonstrate that he’d be a proper presidential choice. We have a population that, over the past 15 years, has lost its innocence, and has been willing to tolerate a certain degree of corruption, but the problem for Malema is that everything about him reeked so much of corruption. He needs to get rid of that stench.

A judge once said of Gary Porritt, the former CEO of Tigon who was arrested in 2002, that had he put his mind to legitimate business, he would be such an asset to South Africa. You’ve described Malema as the most talented politician we have – how would you quantify his wasted potential?

The opportunity cost is massive. Can you imagine if Malema – a man with an almost unique ability to reach people, to lift up crowds, and fire them up – was on the straight and narrow? If a guy like that was behaving ethically, people would even argue to change the constitution to make him president for three terms, that’s how charismatic he is. So the question is, what happened? How did he get derailed? And I think the answer lies in his childhood, where he was brought up without a father in Seshego, with severe trauma. He spent his formative years in the ANC, where he was exposed to a party slowly corrupting. He saw ANC figures like Patrice Motsepe and Cyril Ramaphosa suddenly benefiting from BEE deals with giant companies, and accruing massive amounts of wealth. He saw people earning fast money, and it must have seemed grossly unfair, and something in him twisted.

Do you think this indicates he doesn’t believe what he does is wrong?

Oh no. Let’s be very clear – Malema knows right from wrong. He knows it, because he now goes out of his way to hide it, so he knows what he has done is not acceptable. That’s clear from the fact that he has become far smarter about hiding apparent wrongdoing and keeping his fingerprints off what he does.

This is a book which has taken many years to write; how difficult was the process?

Well, it was difficult for a number of reasons. First, Micah and I have very different styles: we didn’t always agree on the politics, and I was willing to take far larger risks than he was to get the truth out, and Micah is very meticulous with the facts, as you should be. But secondly, some of those human stories from VBS were really emotionally draining. There was one woman, Margaret Chauke, who lost her life savings of R68,000 which she’d put with VBS. I visited her a number of times, and the last time I saw her, she’d lost her teeth, she’d lost about 20kg, and looked so incredibly old, all because of this. She’s poor – Margaret sells mielies, fruit and vegetables in Thohoyandou, hours away from where she lives – but she said to me: “Some days I don’t have food to eat, but what I need is justice.” It was so difficult seeing what this had done to her, I was on the verge of tears. So these human stories of loss drain you.

This book contains a wealth of new information about Malema – documents, court records, details of his life and wealth. How tricky was it to get access to this library of wrongdoing?

That was a huge, huge frustration, and it reveals so much about the lack of transparency in our courts and judicial system. Some of the Sars documents detailing what Malema did were in the court record in the Pretoria high court, but for no justifiable reason, they were locked away in a room where nobody could see them. It showed that there are people in the court system, clerks, who refused to comply with the law and release it. So we had to hire lawyers to get those records. It illustrated that even in the courts, there were people trying to protect Malema. That should never have happened, and it shows why we know so little about what’s really happening behind the scenes.

To some extent, this is a swansong. You’ve left journalism, hopefully only temporarily, but the trade is in a crisis. Economically, print media is battling – last week, the Financial Mail announced it would close after 60 years – so what future do you see for a vital institution of accountability?

It worries me hugely. People would often tell me, when I was being attacked by Julius, how brave I was. But now, so many people are leaving journalism that there aren’t the role models of people holding people to account. Younger journalists facing that sort of thing, without the protection of experienced editors and colleagues, might just think “fuck it, I don’t need to take all of this”, and leave the media. Now, I’m not underplaying the role of the Hawks – had they done their work properly, we’d have far fewer people believing they could behave with impunity, and threatening journalists – but it’s so much harder in this media environment today. I don’t know where this ends. Still, I’ll miss working as a journalist hugely – out of everything I’m going to miss, it’ll be the adrenaline of breaking a big story.

Well, one disturbing new turn is that investigators themselves are being targeted, like lawyer Bouwer van Niekerk, who was assassinated in his office recently. Journalists have traditionally been safe in South Africa, but do you consider these hits an ominous sign?

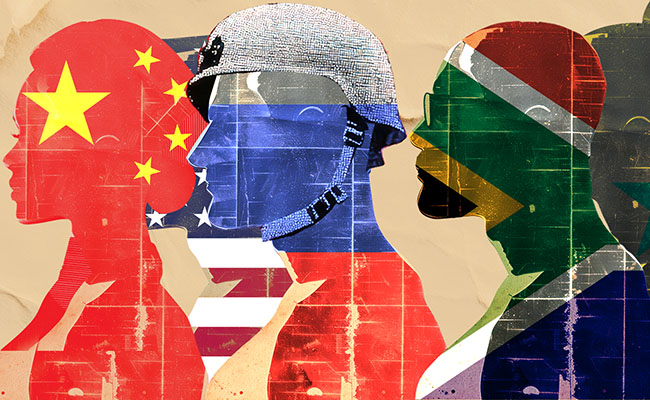

Absolutely. I’ve had threats in my career, but nothing I took seriously. But all of a sudden, it feels as if there is a shift in the probability of journalists being attacked in South Africa. For years, journalists were protected by the extent to which the ANC really fought for media freedom, having lived through what happened during the apartheid era. But the character of the ANC has changed – Jacob Zuma killed the Scorpions, for example – and we now see an era of impunity, where people have become bolder, and see media freedom as less important. And the crooks don’t like being exposed. And what makes this all the more disturbing is that we haven’t seen much energy put into investigate these new assassinations, which is why I think there has been a shift.

The book has met with a fantastic reception – we know books aren’t massive money-spinners, but they can make a difference. This is your first book, a labour of love, and it has taken a number of years to get here. Emotionally, how do you feel about the product?

I’m proud of this. You know, investigative journalists always feel they could do more – there’s always one more strand to pull, one more avenue to go down – but at some point you need to call time.

Top image: EFF leader Julius Malema. Picture: Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.

O really?

With respect- what nonsense.

he has a burning rage inside him- a racism rage.

he has no true public interest at heart.

he has been enriching himself at the costs of public interest.

he is a liar- proclaiming to be for the proletariat, the poor- in the meantime he lives in luxury and had more interest in designer clothing and expensive cars than most politicians.

i normally enjoy your newsletter- please do not insult your readers with clever headings like this.

Quite a blemish on this publication to propagate such drivel.

I truly need to read the book to see the evidence.

For now it sounds like propaganda against Malema.

We have so many white criminals hiding in the Western Cape linked to drugs syndicates. When they you going to investigate them and write us another book?