As Africa accelerates its digital transformation, a new and deeply personal cyberthreat is taking root: romance scams.

According to Jason Lane-Sellers, Director, Fraud and Identity, EMEA at LexisNexis Risk Solutions, these emotionally manipulative schemes are becoming one of the most prevalent forms of cybercrime across the continent, targeting both digitally savvy youth and the vulnerable elderly with devastating effect.

“Romance fraud is particularly cruel,” Lane-Sellers tells Currency. “It exploits trust, loneliness, and the digital platforms people use to connect. And it’s growing fast.”

Cybercrime across Africa is on the rise, following global patterns driven by increased internet penetration, mobile money adoption, and the rise of app-based banking.

However, in Lane-Sellers’ view, Africa is experiencing a “particularly rapid evolution” due to the leapfrogging effect of mobile-first digital access, combined with limited cybersecurity awareness.

In South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya and Uganda – where mobile money and instant payments are now widespread – fraudsters are shifting from technical identity theft to more human-centred scams.

“The trend has moved from identity fraud to scams and account takeovers,” Lane-Sellers explains. “Why hack the bank when it’s easier to manipulate the customer?”

Deep research

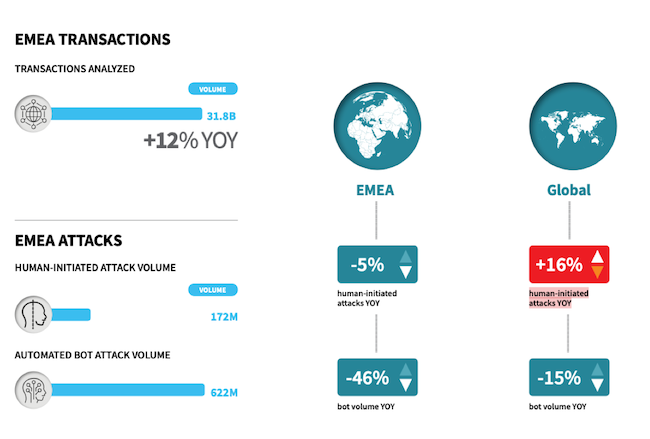

The overall picture is not entirely bleak: LexisNexis has noted a 19% year-on-year decline in attack rates in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), primarily driven by a fall in e-commerce fraud attacks.

These attacks are typically driven via mass emails, and the reduction is due to something called “strong customer authentication”, for example, where your identity is double-checked via an SMS. However, globally, the attack rate still increased to 31-billion attacks last year, a 12% rise year on year.

Romance scams illustrate how cybercriminals are evolving. Fraudsters – often operating from international scam centres, many in Asia – use fake online profiles, stolen or AI-generated images, and emotionally persuasive stories to build virtual relationships. Once trust is established, they ask for money for fabricated emergencies: hospital bills, travel costs or family crises.

“These scams aren’t random. They’re researched,” said Lane-Sellers. “They mine social media for clues, mimic language and use AI to construct believable identities and emotional hooks.”

LexisNexis data suggests romance scams in Africa disproportionately target two groups: young adults aged 18 to 25 and seniors over 65. Young people fall for “get-rich-quick” schemes or fake job offers. Seniors, meanwhile, are targeted for their financial savings and emotional vulnerability.

“There’s a misconception that digital natives are digitally secure. But younger users are often more lax with passwords and more susceptible to emotional appeals,” Gaudel said. “At the other end of the spectrum, older users are more isolated and trusting.”

The scams can be elaborate. In one European case cited by Lane-Sellers, a woman was manipulated over months into believing she was in a real relationship, ultimately sending thousands of dollars in support payments to someone she had never met.

These manipulative tactics are often run through “scam centres” – corporate-style operations with departments for targeting, scripting and follow-up. Some even involve human trafficking, with workers forced to make scam calls under duress.

Romance scams are just one manifestation of a broader fraud ecosystem that now rivals legitimate business operations in sophistication. Criminal groups increasingly use AI to craft scam messages, spoof bank interfaces and mine personal data. They operate internationally, targeting consumers across borders and laundering money through complex crypto or gaming platforms.

“The fraudsters are professional,” Lane-Sellers says. “They test, scale and segment their targets just like any business would.”

LexisNexis Risk Solutions’ annual cybercrime report, which Lane-Sellers oversees for the EMEA region, shows fraud patterns that shift rapidly across geographies. Africa’s unique vulnerability stems from rapid digital adoption, varying levels of regulatory preparedness, and fragmented consumer education.

What can be done?

Banks in South Africa have made progress in raising public awareness by embedding anti-scam messaging into their digital platforms and advertisements. However, Lane-Sellers warns that education campaigns alone are insufficient.

“Fraud detection needs to evolve. Banks should be able to tell not just who is transacting, but how – and whether they’re being manipulated,” he says.

Behavioural analysis can detect signs of social engineering, such as unusually long transaction times, the use of remote access tools, or users being on phone calls during payment processes. These are red flags that may suggest manipulation.

Legal reform is also key. Lane-Sellerscalls for better cross-border data sharing, fewer regulatory hurdles to exchanging fraud intelligence, and stronger safeguards for mobile money users.

“Fraud isn’t local. Criminals are international, so defences have to be too,” he says. “We can’t fight this if banks, telcos and law enforcement agencies remain siloed.”

Africa’s romance scam epidemic is a symptom of a larger problem: the gap between digital inclusion and digital security.

As more Africans go online for love, work and finance, they must also learn to navigate a growing landscape of deception. The solution lies in a blend of technology, co-operation and awareness – before more hearts and wallets are broken.

- An earlier version of this article miss-identified the interviewee. Apologies for the error.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.