Who would have thought Flying Fish would be the future of South African Breweries? It’s not yet a dominant trend, but if recent results of drinks and brewing companies are anything to go by, glacial trends are now noticeably moving global drinks markets.

Ever heard of “zebra striping”? It’s a widely held view that younger generations, including millennials and Gen Z, are drinking less. But recent trend analyses suggest this is not entirely true – something different is happening.

On average, alcohol consumption is down. Euromonitor noted in October 2025 that only 23% of consumers globally reported drinking alcohol at least weekly in 2025, while 53% of drinkers said they were actively trying to cut back (up from 44% five years earlier). It also said 36% of legal-drinking-age Gen Z had never consumed alcohol.

But the International Wine and Spirits Record (IWSR) have a more subtle interpretation: younger consumers are more likely to be “situational” or “occasional” moderators, drinking only at weekends or on special occasions, or avoiding alcohol at set times (training, Dry January, etc.). They are “zebra striping”: alcohol, then no alcohol, then alcohol.

The IWSR has argued against the neat headline that “Gen Z is abandoning alcohol”, noting that usage among legal-drinking-age Gen Z rose from April 2023 lows and that their propensity to go out and spend more has been recovering.

The point, then, isn’t a single, generational verdict. It’s a behaviour mix: more situational moderation, more stop-start consumption patterns, and a bigger role for no/low.

The brewing and drinks industries have been trying to meet this challenge aggressively. Few are specifically categorising the changes, and the proportion of zero-alcohol brands sold by the big drinks companies is not normally disclosed. We do know it’s small – but growing gangbusters.

And the interesting thing is that it is having different consequences for drinks companies as opposed to beer companies. Once it was thought inevitable that drinks companies would win this race with cheaply produced “alcopops” – often called Ready-to-Drink (RTD) beverages – that resemble sodas or fruit juice. But the pendulum has shifted dramatically.

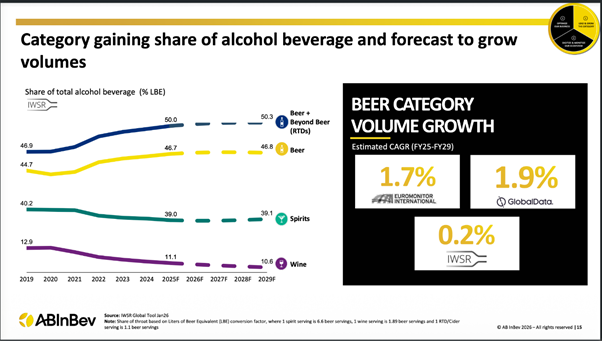

In its latest results, ABInBev, owners of South African Breweries (SAB), noted that after declining in consumption prior to the Covid pandemic, beer consumption has improved while spirts and wine consumption is now on the decline.

ABInBev has had a good year. Even though total volumes were down 2.3%, revenue per hectolitre was up 4.4%. But the standout performance was no-alcohol beer, with net revenue more than doubling since 2021. For ABInBev, the standout performer was Corona 0.0, but other low- and zero-alcohol brands kicked in too.

This is also reflected in South Africa, says SAB CEO Richard Rivett-Carnac: “Both the beer and Beyond Beer categories continued to grow and gain share of alcohol beverages this year, according to our estimates.”

The performance was led by premium and super-premium beer brands, which grew volumes by mid-teens, reflecting the improved economy. But from a trend point of view, the growth is in the Beyond Beer segment, with SAB reporting that it grew volumes by “high-single digits, led by Flying Fish and our spirits-based RTD innovations”.

Brewing the difference

The change in the balance between brewers and drinks companies is visible in their stock prices. Going back three years, the drinks companies were booming, and the beer companies were under the cosh. Much of this was because AbInBev, the brewer market’s largest constituent, was still digesting the acquisition of SAB.

But recently ABInBev has bounced back moderately, recording an 18% increase in value over the past three years. The other big players, Heineken and Carlsberg, have not fared as well, but at least they have not halved in value like Diageo and Pernod Richard.

Why is this happening? Different theories abound, but essentially a bunch of separate forces are all pushing in beer’s favour at the same time – especially versus wine (a market that is structurally shrinking) and spirits, which have had a post-boom hangover.

First, moderation makes beer the “default” alcohol again. When people are drinking less per occasion, they tend to choose products that feel compatible with weekday life. That shift is now described as embedded, not temporary, and it generally advantages beer over spirits.

Second, and for the first time, no/low alcohol is disproportionately helping beer, because it still feels like beer, and the segment is growing fast and becoming a meaningful pillar of the category.

Third, beer “trades down” better than the other categories. In an inflation-pressured world, consumers look for value. Beer often lands in the sweet spot: affordable, familiar and easy to share socially.

Fourth, wine has a deeper structural problem because of its getting hit by price and climate. Global wine consumption has been falling, with the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (called the OIV) reporting 2024 consumption down again to a multi-decade low. Inflation/affordability pressures are a major contributor, and climate impacts have been part of the wider disruption narrative too.

Fifth, the stigma once associated with zero-alcohol beer is now gone, and it’s now seen more and more as “sensible” and “responsible”. But the taste profile is more or less the same.

Perhaps the most eye-catching recent narrative has been a report by online retailer Ocado that non-alcoholic Guinness has overtaken its traditional counterpart for the first time in the brand’s history.

This is just the online market of course, and beer sales are massively dominated by sales in pubs and supermarkets. Still, Guinness 0.0 is now around 8% of total sales, which is significant – and it points to a potentially better future for the beer industry than many analysts gave it credit for a few years ago.

Top image: Rawpixel/Currency collage.

Sign up to Currency’s weekly newsletters to receive your own bulletin of weekday news and weekend treats. Register here.